Imperial Japanese penal official said Korean ‘ideological criminals’ (independence activists) were ‘not well made as human beings’, but ‘if only their thoughts could be corrected, then they will get better’ so they can be ‘used’ for wartime labor, but ‘this is not the case with ordinary criminals’

The following are parts 3 and 4 of an interesting roundtable discussion by Imperial Japanese colonial officials discussing how to best utilize the incarcerated juvenile criminals, ideological criminals, and common criminals under their control for wartime production purposes. Please see this previous post for parts 1 and 2 of this roundtable discussion. Apparently, colonial officials believed that ideological criminals, who included Korean independence activists, could have their thoughts corrected, so they had more labor potential than common criminals, who were perceived to be less reformable. One gullible penal official was apparently duped into paying in part for the Korean clothes of one laborer who had a criminal record for theft, and the official’s home was later burglarized, presumably by the laborer himself.

(Translation)

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) September 12, 1943

Talking about Judicial Protection

Roundtable discussion organized by the head office of Keijo Nippo newspaper – Part 3

Guidance for Increasing Military Strength

Encouraging Prisoners in the Construction of Airfields

Speakers (in no particular order)

- Mr. Fukuzō Hayata, Director of the Legal Affairs Bureau of the Governor-General’s Office

- Mr. Michiyoshi Masuda, President of Seoul Law School

- Major Nishida, Director of Seoul Naval War Office

- Mr. Norimitsu Ohno, Director of the Seoul Court of Inquiry

- Mr. Yūzō Nagasaki, Director of Seoul Probation Office

- Mr. Utarō Sakafuji, Administrative Officer of the Legal Affairs Bureau’s Criminal Affairs Division

- Mr. Yasunori Miyazaki, Secretary of the Criminal Affairs Division, Bureau of Justice

- Mr. Shizuo Kojima, Director, Ideology Division, Korean Federation of National Power

- Mr. Shōichi Fujii, Seongam Academy

- Mr. Masataka Ōkubo, Director of Yasaka Youth Dōjō

- Keijo Nippo: Mr. Akio, Director of Editorial Department, Mr. Mine, Director of Social Affairs Department

Keijo Nippo Reporter: No matter how earnestly we give guidance with love and fervent instruction, I think that there will still be people who will cause trouble for the Bureau of Justice. What are the views of those in the military as to how the subjects of judicial protection should be mobilized?

Naval Major Nishida: I think it would be fine if they are readily used under the firm guidance of companies in the production area that believe that what they are doing is directly useful to the nation. There may be a security issue or two, but in the context of the war, these issues are not so important, and I think this is the quickest way to meet the demands of the nation.

We have used prisoners to build certain airplanes, but I have heard that most of the prisoners were so enthusiastic and happy to know that their work in a place without any comfort services was helping to protect Japan. I have also heard that they were more efficient than those who were used from one group.

I think it would be very good if you could supervise them and assign them to such areas, rather than just suddenly releasing them out of the blue.

Keijo Nippo Reporter: As a specialist, what is your opinion on the problem that crime is preventing the increase in military strength in wartime?

Mr. Miyazaki, Secretary of the Criminal Affairs Division: Recently, the public has been paying a great deal of attention to the issue of production buildup. This is the people’s mindset of responding to the current stage of the war, and anyone who stands in the way must be resolutely removed. Judicial protection is playing a significant role in removing such obstacles.

So far, the goal of judicial protection has been to passively maintain public order, but from now on, it must also get involved in the wartime aspects of life which are directly involved in the production buildup.

The number of Korean subjects of general judicial protection is estimated at around 3,000, and even though it is difficult to figure out what to do once we gather them together, it is not effective to handle them as a dispersed group. The most important thing is to gather them together and use their combined strength towards the goal of increasing production.

Mr. Ohno, Director of the Seoul Court of Inquiry: I have been thinking about what you said earlier, and although I think that people who commit ideological crimes are not well made as human beings, if only their thoughts could be corrected, then they will get better. However, this is not the case with ordinary criminals. In the fall of the year before last, I had some work to do at home, so I hired three laborers from the Seoul Educational Foundation.

I took notice of these laborers who had relatively good potential, so I invited them back to my house several times, so I could work with them and guide them. I thought to myself, if it went well, then there would be much to gain. My wife also felt this way and did various things, such as serving them dinner before sending them home, and letting them take some fruits home.

One of them was 17 years old and had one conviction for theft, but he was completely repentant and said he would do anything to get back on his feet. He said he would figure out something to do even without my prompting, but he eventually came to me and asked if I had a relatively preferential job for him. As New Year’s Day approached, he asked me, “I found this store selling some Korean clothes for 17 yen, but I only have half the money to pay for it. I’m wondering if you could provide me with the rest of the money to help pay for it?” He was just a small 17-year-old child with no parents, so I decided to help him purchase it.

However, he never came again. After a while, my house was burglarized. I cannot believe that my way of doing things was a success in any way, even as a joke. I think it is a difficult question to answer as to why I failed. The judicial protection program is designed to guide and rehabilitate subjects by showing them compassion. It is extremely easy to first show them compassion, but it is extremely difficult to guide and rehabilitate them.

Mr. Miyazaki: Mr. Ohno mentioned that judicial protection services are very difficult to manage. I think that it is very difficult for judicial protection services to remake a subject’s personality into a perfect person.

However, it is not enough for today’s protection services to merely strive towards the perfection of the subject’s personality. When human resources are in dire need of replenishment, it is not enough to perfect the human personality. Instead, I believe that the most important demand for judicial services today is to directly contribute to the buildup of production.

I believe that this is, at the same time, the goal of judicial protection. In this respect, juvenile protection seems to be very easy. There is a possibility that the trial court can place a juvenile in a juvenile reformatory institution or in a judicial protection group and firmly deal with them. Furthermore, ideological criminals under judicial protection also have the probation office to watch over them, so it is possible to put all of their cases together there. But there are difficulties when it comes to general judicial protection.

Mr. Ohno: It’s just two sides of the same coin, isn’t it?

Mr. Satō, Chief of the Protection Division of the Legal Affairs Bureau: That requires organization.

Source: https://www.archive.org/details/kjnp-1943-09-12

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) September 14, 1943

Talking about Judicial Protection

Roundtable discussion hosted by the head office of Keijo Nippo newspaper – Part 4

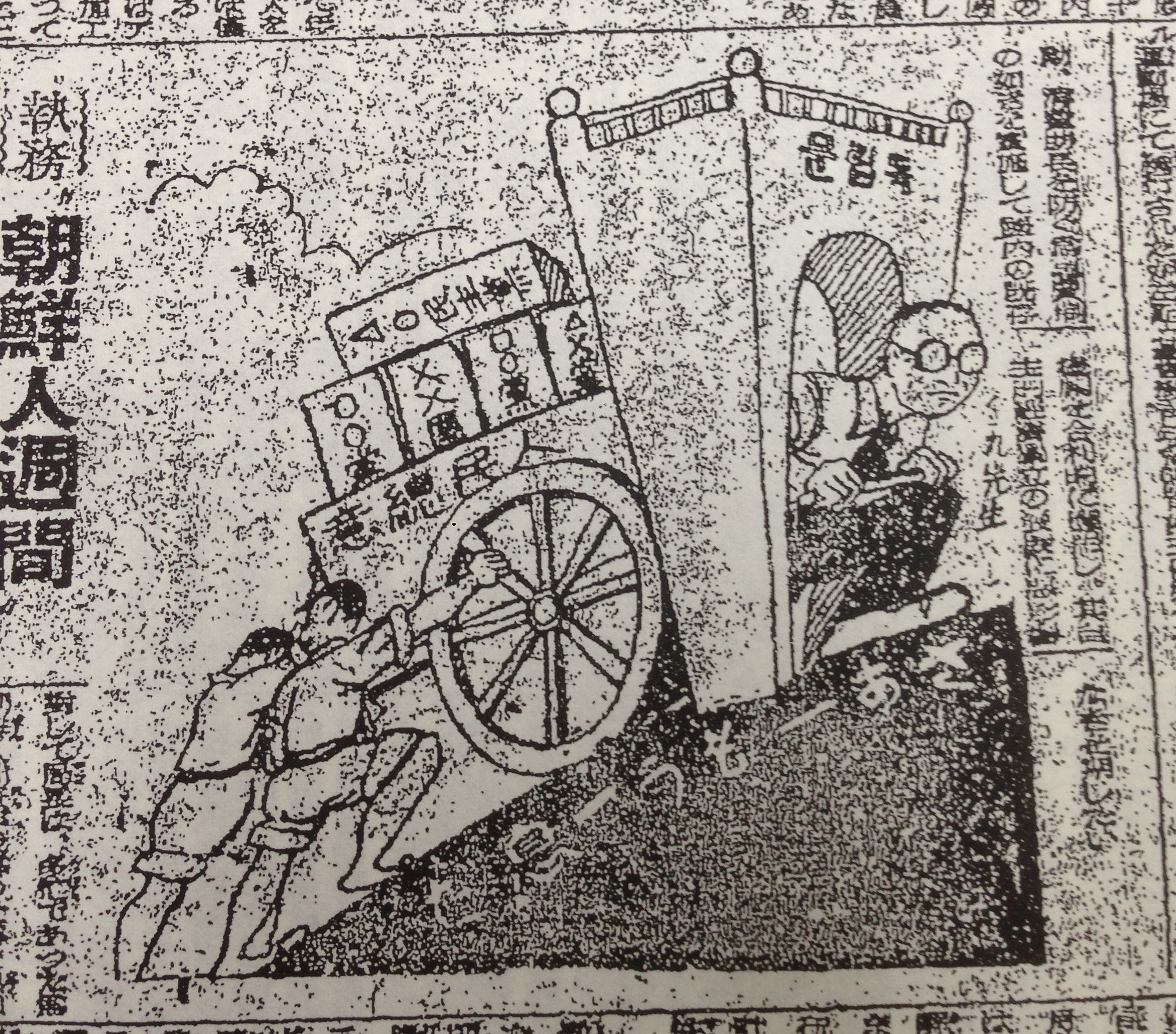

Rehabilitated prisoners who are sent south

Futaba Cram School, a juvenile protection school with an attractive reputation

Keijo Nippo Reporter: I would like you to share your thoughts from the standpoint of judicial punishment.

Mr. Sakafuji, Officer of the Criminal Affairs Division: I am in a position directly related to judicial protection, and from that standpoint, I believe that judicial protection must always move in the same direction as judicial punishment. However, simply viewing things in light of the ongoing current war situation, we find ourselves needing to cooperate in all aspects to increase military strength. In terms of its essential and systemic aspects, judicial punishment has been very passive in nature.

However, in order to break through these various restraints to some extent, and to actively embark on this project, we are currently dispatching a considerable number of people to the south. We have received a large number of requests from those who wish to be dispatched to the south. In general, the volunteers want to gain redemption by serving during wartime, and there is a significant feeling that this desire for redemption can be used towards the purpose of increasing military strength. However, for this reason, we do not send any number of people who wish to join us, but rather we select and train from among those who wish to join us.

At present, prisons also provide special training and technical training for this purpose, but I believe that an organizational plan must be established to mobilize subjects under judicial protection to increase military strength based on the Imperial Way of Labor.

Since subjects under general protection are dispersed, it is acceptable to organize a few protection groups for all of Korea. Labor groups can be organized, and they can become the basis for increasing military strength through work. This is where the way forward for judicial protection can be found.

Keijo Nippo Reporter: Now, Mr. Satō will give us an overview of judicial protection in the past year.

Mr. Satō: Judicial protection can be divided into three parts: juvenile criminal protection, ideological criminal protection, and general criminal protection. The system for juveniles was established for the first time in Korea on March 25 last year, but the law was promulgated on March 23 and came into effect on March 25. That left only two days to implement the law, which did not leave enough time to actually implement it. I must say that most of last year was spent in preparation for the implementation of this law.

Last year, we started by appointing juvenile protection officers. The Juvenile Court asked the chief public prosecutors in the six provinces within the jurisdiction of the Seoul Court of Inquiry to recommend suitable juvenile protection officers, and we appointed 151 of them as commissioned juvenile protection officers. The appointments were made on September 18, and it took a considerable period of time just to select the juvenile protection officers. The Juvenile Protection Center has established an organization called Futaba Cram School Foundation with the idea of providing direct guidance for the actual judicial protection of juvenile ideological criminals.

We are in the process of renovating buildings that have been confiscated from enemy states, but when this is completed, we plan to accommodate 200 juvenile offenders in both Incheon and Gongju, and if we give them focused training for two months, just as we do in mainland Japan, we will be able to train about 1,000 people five times a year. If we do not do this, we will not be able to provide actual judicial protection for the approximately 20,000 juveniles in our jurisdiction. In this way, we would like to have them serve in projects related to the current war situation and, if possible, become industrial warriors. The Seoul Juvenile Training Center is currently under construction. It is currently housed in a temporary building in the town of Ahyeon. It began operation in January of this year, but it has a capacity of about 20 students, which is inadequate.

The Juvenile Court began to handle all cases in January of this year, and from January to June of this year, the number of cases it has handled is 980. Since the facilities for the internment judicial protection of these juveniles are not yet complete, they are left in the hands of the protection officers, and we are in a hurry to add collective training as soon as possible.

Keijo Nippo Reporter: What about ideological crimes?

Mr. Satō: Currently, we have [redacted] people under judicial protection for ideological crimes. In the six years since the system started, the number of those placed on judicial probation has totaled 3,500, of which 45 were prosecuted for committing further crimes during their probationary period, so the number of recidivists is small. Our aim is to have passive allies and true converts alike devote themselves to the service of our country. When I see such admirable things, I am struck by their seriousness. They remake not only themselves, but also embark on the Imperialization movement, so that there are 44 Japanese language institutes and 12,000 graduates of those institutes, with 6,500 people currently attending lectures. In addition, we are making considerable efforts to ensure that the purpose of the conscription system is thoroughly understood.

Next, I would like to mention the activities of the Judicial Protection Commissioners. Last year, we appointed 4,500 commissioners in all of Korea. As of the end of June, there were 3,513 subjects under the oversight of the commissioners, of which 34 have been found to have committed a second offense. Considering the fact that the number of so-called previous offenders who committed a second offence during the probationary period is one third the number in previous years, I think 34 is a good result.

Keijo Nippo reporter: Lastly, what are your hopes for the general public regarding judicial protection?

Mr. Hayata: It is thought that judicial protection has always been considered to be important, but in the past, the critical importance of judicial protection was forgotten. Although the general public has become more aware of this issue, it is still not enough. I would like to see this point thoroughly raised, especially in newspapers and magazines.

In particular, I believe that the most important thing in this emergency situation is to maintain security in the home front. I am glad to see that the judicial protection activities have made considerable progress, but I think it is most necessary to secure human resources as well as to maintain security.

This is a particularly important issue in the current decisive war situation. In this sense, I would like to ask the general public to firmly pull those who are subject to judicial protection in the right direction. If we do so, we will be able to maintain public order and secure scarce human resources, which will immediately help to strengthen our armed forces. I would like the general public to be well aware of this.

Keijo Nippo Reporter: Thank you very much for your time.

Source: https://www.archive.org/details/kjnp-1943-09-14

(Transcription)

京城日報 1943年9月12日

司法保護を語る

本社主催座談会3

戦力の増強へ指導

飛行場の建設に囚人の奮励

語る人 (順序不同)

- 総督府法務局長 早田福蔵氏

- 京城法学専門校長 増田道義氏

- 京城海軍武官府 西田少佐

- 京城覆審法院部長 大野憲光氏

- 京城保護観察所長 長崎祐三氏

- 法務局行刑課事務官 坂藤宇太郎氏

- 同刑事課事務官 宮崎保典氏

- 朝鮮聯盟思想課長 小島倭夫氏

- 仙甘学園 藤井祥一氏

- 弥栄青少年道場長 大久保真敬氏

- 本社側:秋尾編輯局長 嶺社会部長

本社側:指導が如何に切々たる愛情と烈々たる教導を以てしても、やはり司局の手を煩わす人間が出て来ると思うのですが、それら司法保護の対象者を動員しようとする場合、軍の方ではどういう風にお考えですか。

西田海軍少佐:自分のやっていることが、直接国家のお役に立つという生産方面の会社あたりでしっかりした指導のもとにどしどし使って頂いたら結構だと思います。その中には治安的な一、二の問題もありますが、戦うという意味においてそれらの問題はそう重要視すべきものではなく、これが一番手取り早い国家の要求に応ずる途だと思います。

ある方面の飛行機を作ります際、囚人を使用したこともありますが、そこに来て居った大部分の囚人は何等慰安もないところで自分達の働いていることが日本を守る力になるのだという非常な熱意と喜びを以って、却って一班から採用しました者より能率をあげているような話も耳にしております。

こういうようにいきなり放すのではなく、一面監督しつつそういう方面にあたらして行くようにされたら非常にいいんじゃないかと思います。

本社側:犯罪が決戦下の戦力増強を欺く妨げておるという問題につきまして専門の方から。

宮崎刑事課事務官:最近は生産増強という問題に非常に国民の関心が向いて来ています。それは戦争の現段階に応じようとする国民の心持であり、その邪魔をする者は断乎として除去されなければならないのでありますが、それを取り除けるために司法保護が相当大きな働きをしております。

司法保護の行き方も大体今までは消極的な治安の維持というようなところにその目標があったが、今後はそれに加えて生産増強に直接ぶつかって戦争生活にまみれるという行き方で行かなければならないのではないか。

朝鮮の対象者は一般保護の方は三千幾らということですが、これを集めてどうするということは困難であるにしても、これを分散したものとして取り扱って行くことは効果的でない。集めて綜合された力を発揮することが一番必要で、而もその目標は生産増強に向けることです。

大野京城覆審法院部長:先程から色々御話を伺って考えて見ますのに、思想犯を犯す者は大体人間が出来ているのではないが、その思想さえ直せばよくなるのではないかと思うのです。ところが普通犯はそうは行かない。一昨年の秋、私の家庭に仕事があったものですから、京城教護会から三人の人夫を傭って使って見ました。

その内比較的見込みのある者に目をつけまして、その後再三家に呼んで見て働かせると共に出来たら導いてみよう。うまく行ったら儲けものだという気持ちでやって見たのです。家内もそういう気持ちで夕飯を食べさして帰したり、果物を持たしてやったりして色々とやっておりました。

その中の一人十七歳で窃盗前科一犯のものがいましたが、すっかり悔悟し何とかして立ち直りますと言います。なってこちらが呼ばなくとも何かそうすると。しまいに、私のところで比較的優遇というような形に仕事はないかと言って遊びに来る。そのうちお正月が近くなったが、何処そこに朝鮮服のいいのが十七円であるけれども、半分だけ自分が持っているけれども、あとの半分は何とかならんでしょうかというので、ついこちらも十七位の小さい子供であるし、親もないというので、そうかといって買わしたのです。

ところがそれきり来なくなった。暫く経って、私の家に泥棒がはいった。この事実を考えて見て自分のやり方が冗談にも成功だとは思えない。何故失敗したか、これは却々難しい問題だと思うのです。司法保護事業というのは対象者に憐憫の情けをかけて導いて更生させてやることですが、最初に憐憫の情けをかけることは極めてやさしいが、それを指導し更生させるということは極めて難しい。

宮崎氏:今大野さんから司法保護事業が大変難しいというお話があったのですが、一人の対象者を人格的に完全な者に創り直すということは、保護事業にあっては非常に困難だろうと思います。

しかし、今日の保護事業は人格の完成に向かって行くのでは足りない。現下人的資源の充足が切望されているとき、人格の完成を持っても間に合わない。それより、生産の増強に直接役立って行くということが現下の司法事業に対する最も大きな要請ではないかと思います。

これは同時に司法保護の目標ではないかと考えます。その点少年保護は非常にやり易いように思う。審判所で少年院、或いは保護団体に預けて一応固めてやれる可能性がある。更に思想保護も保護観察所があって一応そこで引っくるめることが出来るからです。一般保護に至っては困難であります。

大野氏:それは結局裏と表で、同じことではないですかね。

佐藤法務局保護課長:それは組織が必要なんですね。

京城日報 1943年9月14日

司法保護を語る

本社主催座談会(完)

南に更生の刑余者

名も床しい少年保護の二葉塾

本社側:そこで行刑の立場から伺いたいと思います。

坂藤行刑課事務官:私の方は司法保護に直接関係の深い立場にあるのですが、その立場から常に行刑の一つの方向に司法保護も向かって行かなければならぬ、と考えておりますので、行刑の方から簡単に申しますと、決戦連続の現下の情勢に於きまして、どうしても戦力増強の方面に全面的に協力して行かなければならないという立場にありますので、行刑方面に於きましても相当その方面に進出しているつもりでありますが、もともと行刑というものは制度的に見まして或いは本質的に見ましても非常に消極的に出来ている。

併しそうした色々な拘束をある程度打ち破って、積極的に乗り出そうということから、今南方へ相当派遣しておりますが、希望者を募って見ると相当多数の希望があるのです。大体に於いて決戦下贖罪の気持ちを戦力増強の方面に役立たして貰いたいという気持ちも多分に含まれておる。併しそれがために何人でも彼人でも希望者を送るのではなく、その希望者の中から錬成して遣っております。

現在刑務所においても、そのために特別の錬成を施すとか、或いは技術訓練を授けるという方法でやっていますが、司法保護においても皇国勤労観というものに立って戦力増強の方面に動員するという組織計画が樹てられなければならないのではないか。

それには一般保護方面は分散していますから、これを数個の保護団体或いは全鮮を通じてもよいが、勤労班というものを組織して、それに基いて一つの戦力増強方面の作業に就かしめる。そこに司法保護の進歩する道が発見されるのではないか。

本社側:では、佐藤課長さんから過去一年間に於ける司法保護の概要について。

佐藤氏:少年と思想と一般の三分野に分けて申しますと、少年については昨年の三月二十五日に朝鮮で初めて制度の創設を見たが、法令の公布が二十三日で、施行が二十五日、その間二日しかないため、実際施行にはなったが実施は出来ないのであります。それで昨年中は殆ど実施の準備中であったというように申さなければならないのであります。

昨年先ず少年保護司の任命から開始したのでありますが、少年審判所は京城覆審法院管内六道に亘って各地の検事正にお願いして少年保護司の適任を推薦して戴き、その中から百五十一名を嘱託少年保護司として任命致しました。これが九月十八日で相当の期間を、少年保護司を選択するだけでも要したのであります。少年保護団体は思想犯保護の実際に鑑み直接指導するという考えの下に財団法人二葉塾という団体を作りました。

最近漸く仁川と公州に敵産を借り受けて修理中ですが、これが完成すると両方で少年犯二百名を収容する予定で、これを内地でやっているように二ヶ月間錬成一点張りで鍛えて行きますと、年に五回、約千名位の錬成が出来ると思う。そうしないと管内約二万位保護を要する少年があるので、実際の保護は出来ない。このようにして時局に関係のある事業に奉仕させ、出来れば産業戦士としたい理想をもっている。京城少年院は目下建築準備中である。現在阿峴町の方に仮庁舎があって、本年一月から収容を開始しているが、収容定員が二十名位で、これでは不十分であります。

少年審判所が一切の事件を処理し出したのは本年一月であるが、本年一月から六月まで処理したものが九百八十件である。これらの少年を収容保護の施設が未完成なため、保護司の手に委ねている状態で、一刻も早く集団的修練を加えたいと焦っております。

本社側:思想犯はどうでしょう。

佐藤氏:現在〇〇名の対象者を保護しています。制度開始以来六年間に保護観察処分に附した者が三千五百名になっていますが、その内観察中に更に犯罪を犯して起訴されたものは四十五人です。かく再犯者が少ないというのは、消極的な味方であって、本当に転向した者は一身を捧げて御国のために奉公することが狙いです。そうした感心なものを見るとその真剣さに打たれます。自分だけの再生ではなく、それらのものが皇民化運動に乗り出していて、その国語講習所が四十四ヶ所ありますし、そこの修了者が一万二千、目下講義をうけているものが六千五百名という状態であります。その他徴兵制の趣旨徹底ということには相当尽力しているのです。

次に特に申し上げておきたいのは司法保護委員の活動であります。全鮮で昨年四千五百名の委員を任命しました。委員の対象者が六月の末に三千五百十三名、その中再犯の明かになった者は三十四名。従来所謂前科者の三分一が再犯者になっていた事実から申すと三十四名はよい成績と思います。

本社側:最後に司法保護に対する一般民衆への希望を早田局長にお願いします。

早田局長:司法保護のことはもとより重要なことに考えられていたが、大体従来は一番大事な保護というのを忘れていた。一般にもこれに関する認識が大分強まっては来たが、まだ十分だといえない。この点については特に新聞や雑誌などによって大いに徹底せしめて貰いたいと思います。

殊にこの非常時局に於いて一番大切なことは銃後の治安維持であると思います。これが司法保護の活動によって相当の成績が挙げているということは嬉しいが、その治安の保持と共に人的資源の確保ということが最も必要であろうと思います。

今の決戦態勢下、特にこれが重要な問題であります。その意味に於いて一般社会の人々が司法保護の対象になる者をその方面にしっかり引っぱっていって貰いたい。そうすれば治安の維持も不足している人的資源も確保され、直ちに戦力の増強に役立つと思うのであります。このことを一般大衆によく知って貰いたく思うのであります。

本社側:長い間有難うございました。