Simon Young Kim (김영근), a South Korean violin virtuoso and disciple of famous violinist Jascha Heifetz, Simon was once my teacher and mentor, and his son was my best friend in elementary school

Simon Young Kim is a violin virtuoso who is apparently somewhat of a celebrity in the South Korean classical music scene. When I was in elementary school, he was also my mentor and violin teacher. His son, whom I will call ‘Alex’ in this post, was my classmate and best friend at school (not using his real first name to respect his privacy). This post is my recollections of my time spent with Simon and Alex as a child in the late ’80s.

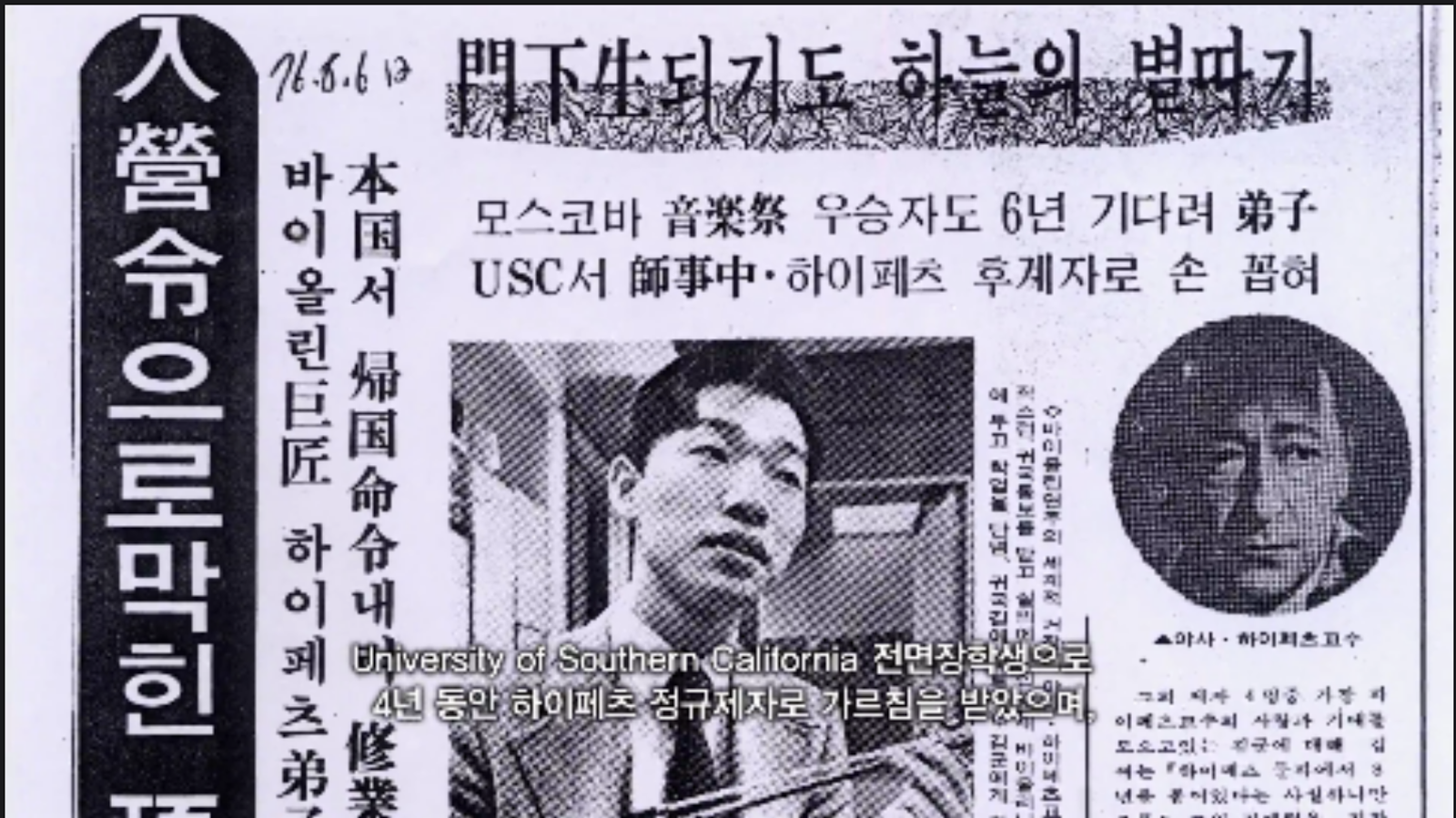

Simon Kim is well known as a disciple of famous violinist Jascha Heifetz (1901-1987), and he has played for many symphonies and taught countless students throughout his long music career. You can find videos of his performances and articles about his life by Googling “Simon Young Kim” or “김영근 바이올린” (“Kim Young-geun violin” in Korean). However, I believe the articles forgot to mention one important aspect about his work: that he was not only a good violin teacher, but also a great ambassador for Korea, in that taught his students about his homeland. In this way, he had a big influence on my own attitudes about Korea and the Korean people.

Simon Kim started learning violin when he was seven years old. As a child prodigy and as a young man, he performed at concerts touring all over the world. One day, he had a rare chance to audition for Heifetz, who then accepted him as a student. However, he could not immediately go to the US to study under Heifetz, since he did not fulfill his military service in South Korea. In 1973, Mrs. Yook Young-soo, the wife of South Korean dictator Park Chung-hee, intervened to let Simon Kim leave to go to the US. Mrs. Yook was subsequently assassinated the following year in 1974. Since then, his long music career has taken him to San Diego, Honolulu, and Boston, with performances all over Japan, Korea, the United States, and Canada. A few years ago, Simon moved back to South Korea to teach top music students in Seoul. Source: 하이페츠 연주법으로 고국에 보은하고 싶다! (m-economynews.com)

But when I first met him and his family in the late ’80s, I was a Japanese kid in elementary school living with my parents and my sister in a small New England town. I was unhappy at the time, because I got to personally see both the US and Japan by traveling back and forth between the two countries, and I felt that life in the US sucked in comparison to Japan. I missed the food, the anime, the manga, the TV programs, the music, the toys, everything it seemed. This was before the Internet as we know it today, so I even used a shortwave radio to listen to crackly Japanese radio programs. I was that desperate to listen to any spoken Japanese that was not from my family, even boring news programs. My grandparents took pity on us and sent us occasional packages of textbooks, magazines, video tapes, and cassette tapes with recordings of our favorite animes, but we still missed Japan. We often resented our parents for moving us to the United States for work.

I also didn’t like my elementary school very much. This was the late ’80s, so some Americans felt threatened by the rise of Japan as an economic superpower, and some teachers directed that hostility towards me to some extent. When classmates learned I was Japanese, their reaction was like, “You’re Japanese? You eat sushi? That’s raw fish, right? Gross!” The student body was not very diverse, and I was one of only a very small number of minority children in the school.

So, I was glad to find that there was one other Asian kid in my class, Alex Kim. Alex and I became best friends almost immediately. Alex, who had lived in Hawaii before coming to New England, told me that there were lots more Asian people in Hawaii, and most Americans knew about Asian food there. I was very jealous and wondered why my family didn’t move to Hawaii. We were in agreement that a lot of our classmates were racist and prejudiced.

One time, he actually brought a large lunch box to school full of what looked to me like Korean-style sushi. I was very impressed by his bravery, since I would not have had the guts to bring a traditional Japanese bento box for lunch and risk ridicule by my classmates. But Alex really didn’t care what other kids thought of him, and he generously offered to share his lunch with his classmates to let them taste some homemade Korean cuisine, but there were almost no takers. Indeed, the other kids thought he was a weirdo and shunned him in the cafeteria, except me. I was curious about his food, since I had never seen anything like it, but when I tasted it, I thought it was the most delicious food I had ever tasted. It sure beat the peanut butter and jelly or bologna sandwiches that my parents packed for me, or the stale chicken nuggets, cheese pizza, overcooked green beans, and baked beans that we would normally eat in the hot lunch line for a dollar. Those other kids had no idea what they missed out on.

Alex’s example helped me build my self-confidence and not care so much about what other people thought of me. I think we gave each other confidence to be more openly Asian in school. So one day, Alex and I gave presentations to our classmates about our respective countries, and we explained the differences between Japan and Korea. I talked about the Japanese educational system, the clean and efficient Tokyo subway system, and the bullet trains. Alex talked in length about the Seoul 1988 Olympics, which had happened only a year or two before at this point, and how South Korea rapidly developed in the past few decades. After that, I believe that our classmates’ attitudes toward us slowly started to change for the better.

National Geographic article about South Korea in 1988: https://imgur.com/gallery/hIQKHmX

My old Reddit post featuring the above article: https://www.reddit.com/r/korea/comments/iengmt/south_korea_in_1988_national_geographic/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

One day, Alex invited me over to his house, where I got to meet his father Simon. I listened with interest as Alex spoke Korean to his father, the first time in my life that I ever witnessed Koreans speaking Korean to each other. My first impression listening to spoken Korean was that the endings of Korean sentences sounded somewhat Japanese-like with “-nida”, “-nika”, etc.

I noticed that there was no TV set in the house. Simon explained that he did not find it necessary to have television in the house, because then his son could concentrate on reading books instead. The Kim family did not have beds in the house yet, but they did have mats and Japanese-style futon bedding which looked just like the ones that our family used in Japan.

Naturally, the conversation turned to music. I explained to him that my sister and I were playing both the piano and the violin. My sister was much more talented with the violin, preferring it over the piano, whereas I tended to like the piano more than the violin.

Simon asked me how I felt about living in the US. I feel kind of embarrassed about it now, but I gave a rather extreme answer, telling him that I thought that the United States was hell, and Japan was heaven. I contrasted Tokyo and New York City, drawing from my own personal experience of living in both cities. I argued that Tokyo’s subways were clean, safe, modern, and efficient while New York subways were dirty and scrawled with graffiti everywhere, crime-ridden, antiquated, and inefficient. I went on to say that Japan was clean, safe, orderly, efficient, polite, with better food, TV, anime, music, and toys.

Simon Kim patiently listened to my rant with some bemusement, but then he expertly pivoted our discussions to my dreams. What do I personally want to do with my life? He said that the best country for you to live in is the country that offers you the most opportunities to pursue your dreams. He told me about his own life and asked me if I knew what a military dictatorship was. I didn’t know what it was. He explained and told me that he grew up in a country under a military dictatorship, where his opportunities to pursue his dreams were limited. He was only able to leave South Korea with much difficulty to pursue his dreams in the United States, study under Heifetz, and teach music to students.

I was only an elementary student at the time, but it did sort of make sense for me then. He did mention his Christian faith and the fact that Christian missionaries did not complain when they went to third world countries that were very inconvenient to live in, because they were pursuing their dreams of helping people. I still missed Japan, but Simon Kim helped me think a little more about the different possibilities about my own future, and be a little more grateful about my educational opportunities now. After all, unlike my counterparts in Japan, I was learning fluent English, which could help me in all sorts of different career paths, especially since I already knew my native Japanese.

Simon then told me that his parents also spoke Japanese. I was surprised, and I questioned him some more. Then he told me that there was a time when the Japanese controlled Korea, so that’s how they learned Japanese. I asked him, what do Koreans think of the Japanese language? Simon explained that, since the Koreans were forced to learn it under Japanese rule, many Koreans didn’t have good feelings about the Japanese language.

I thought about it, then it made sense for me in a certain way, analogizing the Japanese language with the piano. I enjoyed playing the piano, even though my parents initially had to force me to practice. But other kids might not necessarily grow up enjoying the piano like I did, no matter how many times their parents forced them to practice the piano.

Growing curious, I asked my parents what Japan did to Korea when it was a Japanese colony. My parents struggled to answer this question, but answered to the effect that the Japanese government forced Koreans to do things they didn’t want to do, like speak Japanese, worship the Shinto religion, adopt Japanese customs, and that the Koreans were still mad about it. My curiosity stoked even more, I asked for more details, but my parents shut me off, ordering me to stop being so obsessed with lurid subjects.

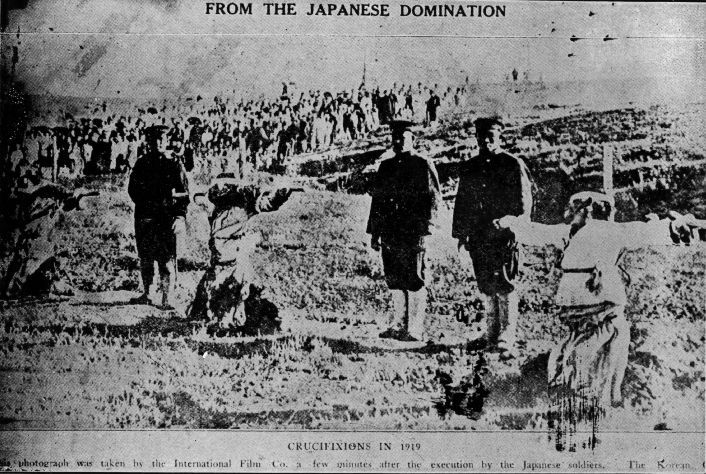

I went back to my friend Alex and asked him if he knew about this history. Alex reassured me that, since his family was Christian and practiced forgiveness, he didn’t hold a grudge against me or Japanese people in general. But Alex told me that the Japanese in Korea were pretty bad. How bad? Alex and I headed to the library. We used card catalogs to look up some books, and then we found an old historical book that had some old black-and-white photos of the aftermath of the Sam-il Korean independence uprising in 1919. Particularly disturbing were the photos showing the Imperial Japanese soldiers standing guard as Korean rebels were crucified and burned. I was not supposed to see these as an elementary student, but here I was, looking at them. Don’t these guys look like the Romans crucifying Jesus? Yeah, it was that bad, Alex whispered.

Later, Simon Kim took me in as a music student very briefly to correct my bad habits with my posture, but then he accepted my sister as a violin student. Today, she is quite an accomplished amateur violinist. I eventually gave up the violin and concentrated on the piano. I improved enough that, by adulthood, I could play some decent jazz pieces to sheet music, and I recently played the piano accompaniment to my sister’s violin performance. After finishing elementary school, Alex and I went to separate middle schools, and I lost touch with Simon and Alex after we moved away from New England. But throughout the years, I would still reminisce about those days I spent in New England with Alex and his family.

Those fortuitous meetings with Simon and Alex kindled my interest in history which continues to this day. I cultivated my Japanese-English bilingualism over the years, and I also learned other languages, like Spanish, German, and Mandarin Chinese. As a college student, I studied in Germany and marveled at the frank and open discussions that Germans could have about the dark aspects of their history under totalitarian regimes. I researched my own family history and learned about my grandfather’s military service as an Imperial Navy doctor in China, Indonesia, and the Pacific Islands during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II. I visited Northeast China to examine the traces of its history under Imperial Japanese occupation. I read a lot about the experiences of Zainichi Koreans in Japan and the discrimination that they experienced.

I also followed with much concern the international flash points that have made the news in recent years and inflamed tensions between Korea and Japan, like Dokdo and comfort women. Many Japanese right-wing commentators observing the passionate anti-Japanese protests in South Korea would dismiss these protesters as all having a mental illness called Hwa-Byung, being unable to properly deal with their own personal anger issues. I found such racist caricatures of Koreans very troubling, since I knew that their anger was legitimate, especially given my increased knowledge of the history of Imperial Japan and my personal friendship with Simon and Alex.

However, as I closely followed what the protesters were saying, I noticed that no one was saying things like “you committed cultural genocide on us!” or “you tried to wipe out our language!” I was confused as to why the Korean protesters did not also protest the cultural and linguistic genocide that Imperial Japan attempted on the Koreans, which I thought would be the overarching issue that not only covers Dokdo and Korean comfort women, but also many other abuses under Imperial Japanese colonial rule. To me, it was almost like if the Jews neglected to mention the genocide of their people, and instead just focused on the confiscation of their property and the rape of their women. But then it occurred to me: maybe those protesters really don’t know about these aspects of their own history that well, and that’s way they weren’t being brought up in the protests.

The Imperial Japanese authorities believed in a totalitarian ideology called the Imperial Way (皇道, kōdō) as they colonized Korea. Motivated by the Imperial Way, Governor Koiso put Korean girls in concentration camps to marry them off to Imperial Japanese soldiers. Motivated by the Imperial Way, Governors Minami and Koiso tried to eradicate the Korean language. Imperial Japan attempted cultural and linguistic genocide on Korea.

Yet these basic historical facts are not as well known or talked about as much as the basic facts about the Holocaust. Hitler believed in a totalitarian ideology called National Socialism, or Nazism. Motivated by Nazism, Hitler put Jews in concentration camps. Motivated by Nazism, Hitler tried to eradicate the Jews. Many more people in the world know these basic facts about the Holocaust than about the Imperial Japanese colonization of Korea.

It was clear to me that, among Koreans in general, there was a deep reserve of unresolved anger that was not far beneath the surface, because they all knew that they were somehow wronged in a profound way by the Imperial Japanese who colonized them. However, while Koreans generally know about some colonial policies, like Sōshi-kaimei (創氏改名, pressuring Koreans to adopt Japanese names), the imposition of the Japanese language, and the exploitation of Korean comfort women, few knew about Minami (the self-proclaimed Father of the Korean Peninsula) or Koiso and their key roles in the attempted cultural and linguistic genocide of the Korean people. If they did, there would probably be more effigies of them burning in the streets and more defaced images of their faces on posters alongside Shinzo Abe‘s effigies and defaced images.

I believe that, without sufficient knowledge about how the ideological belief system of Imperial Japan worked and how the decisions of the key political leaders of Japan-colonized Korea led to these oppressive colonial policies towards the Korean people, it’s hard to channel anger effectively. What would things be like, if the Jews didn’t know that Hitler put them in death camps, that Hitler tried to eradicate them, that Hitler believed in a totalitarian ideology called National Socialism? I venture to guess that, if the Jews didn’t know any of this, they would probably just aimlessly blame the entire German people for what happened to them. That’s why I believe that proper historical knowledge is an important first step towards a proper Vergangenheitsbewältigung, or properly dealing with the past.

The more I learn about the unresolved historical issues between Korea and Japan, the more daunting they seem. I have felt at times hopelessness and at times felt anger towards the Imperial Japanese leaders who committed these crimes in the first place, and also towards the postwar Japanese leaders who left these issues unresolved and passed them onto the younger generations instead. However, I always look back at my memories of my great friendship with Simon and Alex and remind myself that true reconciliation between Koreans and Japanese is still possible.

The closest that the postwar Japanese government ever got to issuing a formal apology was the Kono statement of 1993, which specifically addressed the wartime comfort women issue, and the Murayama statement of 1995, which acknowledged that “Japan … through its colonial rule and aggression, caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries, particularly to those of Asian nations”. However, it became clear that most of the key leaders of the Japanese government were not on board, and those statements were fiercely criticized.

Those statements were ineffectual not only because they did not reflect the views of the majority of the leaders of the Japanese government, but also because it did not do enough justice to acknowledge the severity and seriousness of the crimes that were committed. Cultural genocide is a very serious matter. The crime victims were not statistical figures. Rather, they were families and individuals who each had their own stories of humiliation and degradation to tell. Korean schoolgirls who were ordered to rat out fellow students who spoke Korean. Korean farmers who sent off all the rice that they made to Japan, while only receiving Manchurian chestnuts in return. Countless Korean civilians who were killed during the suppression of the Samil independence movement of 1919. The list goes on and on, and some of their stories are documented on this blog.

I don’t pretend to have the answers to these difficult questions. I’m just one individual, and there is little that I can personally do as one person. But the one baby step that I am taking on my own is maintaining this blog, which translates some contemporary Japanese news articles published in Japan-colonized Korea which document some disturbing things that I believe merited closer study. By making these articles more accessible to the international audience, I am hoping that I am moving the historical discussion in a productive direction. Ideally, a government or institution would be doing this work, but since no one else is doing this, I am taking the initiative and doing this as a private citizen.

Many of you will notice that this blog is ad-free, so I am not making any money off of it. This is a purely a nonprofit activity that I am personally paying for as my way of giving back to the community. Simon Kim, who has selflessly given back so much over his long music career, is my inspiration as I continue maintaining and expanding this blog. I hope this blog can continue to be a helpful resource to you as we continue to try to make sense of this crazy world.