Nostalgia for Imperial Japan and its undercurrents in Kishi Nobusuke’s legacy in postwar Japan, in Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan’s legacy in South Korea, and why access to wartime newspapers of Japan-occupied Korea is important to combat historical misinformation by the far-right in both countries

In a previous post, I explained in detail the intractable movement of historical denialism and revisionism that is prevalent in Japan as a powerful network of academics, businessmen, and politicians that reaches even into the top levels of the Japanese government. I’ve shown how their emotional investment leads to them closely identifying themselves with the Imperial Japanese regime and military, to the point where they believe that, if the honor of said Imperial Japanese regime and military is sullied, then the honor of modern Japan and the Japanese people is likewise sullied. I’ve demonstrated that this is what contributes to their willful blindness and blanket denial when they are confronted with the testimony of comfort women and other pieces of important historical evidence. I suggested that the fading of war memories was helping to give rise to the historical denialist and revisionist movement in Japan, and I proposed countering this rise in part by making primary historical resources like wartime newspapers (for example, Kyeongseong Ilbo) more accessible, to help refresh these war memories.

But there is more. After spending more time researching and reflecting further, I realized that I could have framed the problem better by tracing how the undercurrents of Imperial Japanese ideology were carried into postwar Japan and South Korea through their respective postwar leaders, and how historical misinformation has spread as a result. I have peppered this post with many links and sources for your reference.

To begin our exploration, let’s imagine what life was like in the immediate aftermath of World War II in Japan. Cities were in ruins and many civilians were killed and injured from American air raids. People were starving. The ordinary people were understandably mad at the US, but they were also mad at their own leaders for losing the war. This can be considered the low point in the Japanese public’s opinion of the war criminals. Due to military censorship, the ordinary people’s knowledge of Japanese war crimes overseas was mostly limited to oral stories personally told by the discharged Imperial Japanese soldiers who made it back to Japan.

In the beginning, the American occupation forces sought to reduce this ignorance among the general populace by launching a “war-guilt program” to educate the Japanese public about Imperial Japanese war crimes. At the same time, the Americans also mounted a campaign to absolve the emperor of war responsibility, fearing that chaos would erupt if the emperor was indicted. American propaganda started to paint the emperor as an unworldly figurehead and reluctant warrior, which was actually a myth.

Around 1948, as the Cold War got started, the American occupation switched gears and started to suppress reports of Imperial Japanese war crimes.

… in the years that followed, as the Cold War intensified and the occupiers came to identify newly communist China as the archenemy, it became an integral part of American policy itself to discourage recollection of Japan’s atrocities. Chapter 16, Embracing Defeat by Dower.

As American censorship suppressed reports of war crimes, public sympathies for the war criminals started to grow.

Tojo’s relative ascension in public esteem could be taken as a small barometer to the mood of the times, registering not nostalgia for the war years but an implicit critique of Allied double standards. Chapter 16, Embracing Defeat by Dower.

Defendants who had been convicted and sentenced to imprisonment became openly regarded as victims rather than victimizers, their prison stays within Japan made as pleasant and entertaining as possible. Those who had been executed, often in far-away lands, were resurrected through their own parting words. One remembered the criminals, while forgetting their crimes. Chapter 16, Embracing Defeat by Dower.

When the Allied occupation of Japan ended, the Americans handed back political and economic power to the conservative and right-wing elements of Japanese society.

Driven by Cold War considerations, the Americans began to jettison many of the original ideals of “demilitarization and democratization” that had seemed so unexpected and inspiring to a defeated populace in 1945. In the process, they aligned themselves more and more openly with conservative and even right-wing elements of Japanese society, including individuals who had been closely identified with the lost war. Charges were dropped against prominent figures who had been arrested for war crimes. The economy was turned back over to big capitalists and state bureaucrats. Politicians and other wartime leaders who had been prohibited from holding public office were gradually “depurged”, while on the other side of the coin the radical left was subjected to the “Red Purges.” Chapter 17, Embracing Defeat by Dower.

One of the “depurged” politicians was Kishi Nobusuke (1896-1987), arguably the most unreformed Imperial Japanese ideologue ever to enter the political scene of early postwar Japan. As the top industrial planner of the Imperial Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, he was notorious for conscripting hundreds of thousands of Chinese as slave labor in heavy industrial plants. His attitudes toward Chinese people were summarized as: “We Japanese are like pure water in a bucket, different from the Chinese who are like the filthy Yangtze river”. Kishi was part of the Tojo Hideki government during World War II. After the War, he was imprisoned by the Americans as a “Class A” war criminal. However, he was released since he was considered to be the best man to lead post-war Japan in a pro-American direction. Incredibly, this man managed to become the Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960, leaving office only due to intense pressure from student activists in the Anpo Protests.

In 1961, Kishi had an interesting meeting with Park Chung-hee, the dictator of South Korea, who in some respects turned out to be even more of an unreformed Imperial Japanese ideologue than he was.

At a private lunch with Japanese leaders on his first trip to Japan six months after the May 1961 coup, Park Chung Hee discussed possible “good plans” (meian, 名案) for dealing with South Korea’s pressing problems, economic and otherwise. According to former prime minister Kishi Nobusuke, who had hosted the lunch and was interviewed afterward by Asahi reporters, Park stressed in his accented but fluent Japanese that his experience as a cadet at the Imperial Japanese Military Academy had taught him the efficacy of the “Japanese spirit” and “binta education” (binta kyoiku, ビンタ教育). In a new Japan where such terms harkened back to a militarist past that many Japanese at the time were trying to forget or distance themselves from, even Kishi, who had played a key role in the industrial development of Manchukuo and Japan’s own wartime economy and was later often called the “monster of the Showa era” (Showa no yokai, 昭和の妖怪), admitted to feeling a bit “embarrassed” (omohayui, 面はゆい) by Park’s remarks. But for Park, who had not been back to Japan since 1944, this was the discourse of strength and discipline that he knew and admired from his years at Lalatun and Zama, and it would continue to guide him in the years to come. Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea: The Roots of Militarism, 1866-1945, by Eckert

Binta education above means education with corporal punishment. The word for “embarrassed” used by Kishi connotes a happy sense of being embarrassed, like being flattered. The friendship between Kishi and Park Chung-hee is explored further in a video (https://youtu.be/kO9s3qQcuiY, no English, just Korean with Japanese subtitles) which discusses friendly correspondences between Kishi and Park Chung-hee, and how Park gave awards to Kishi and his associates. This article with a photo showing Kishi on the left speaking with Park in the middle, covers how Shinzo Abe told Park Geun-hye that Kishi and Park Chung-hee were very close (link to article in Japanese).

In his early years as a student at Taegu Normal School (TNS), Park Chung-hee dabbled in German Nazism and Italian fascism in addition to Imperial Japanese ideology:

In addition to Napoleon, Park was strongly drawn to both Bento Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, whose images filled the pages of 1930s Korean and Japanese newspapers and magazines, along with countless stories of Italian and German economic and military resurgence under their leadership. To be sure, admiration for the two dictators as national saviors was not unusual at the time among TNS students, or more generally in Japan and Korea. (…) As a fourth-year student at TNS in 1935-1936, he bought and studied on his own an early Japanese version of Mein Kampf. He also kept two “very large” scrolled pictures in his dormitory, one of Mussolini and one of Hitler, which in a daily morning ritual of reverence he unrolled, hung up side by side, and bowed before, to the astonishment of his fellow students. Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea: The Roots of Militarism, 1866-1945, by Eckert p.102

Park Chung-hee’s approval and veneration of corporal punishment in binta education of the Imperial Japanese military may have led to the pervasiveness of physical hazing in the modern South Korean military and the widespread use of corporal punishment in South Korean schools until relatively recently, when it was banned.

In the 1960’s, Park Chung-hee started the New Community Movement, which was a campaign to modernize rural South Korea incorporating ideas from traditional Korean communalism and didactic techniques that were commonly used in Imperial Japan. Quoting a passage from The New Community Movement: Park Chung Hee and the Making of State Populism in Korea by Han Seung-mi:

Nevertheless, the New Community Movement met with genuine response from the countryside. Its key methodology was spiritual training. It was enforced under guidelines set by Park himself, and “non-economic” mental/social issues were addressed in order for the economy to prosper. Park was influenced by Japanese-style mental training, as were his high-ranking officials and policy advisors, who also believed in a Weberian emphasis on work ethics. “The Swiss had the Puritans, and the Japanese have Ninomiya Ginjiro” (interview, April 1999). Interesting, this comment by a former NCM policy maker at the Blue House was echoed by an elderly farmer in the countryside: “I knew instantly what the president was getting across. It was Ninoyama Ginjiro! He was in our 6th grade textbook!” (Interview with a farmer in his seventies, Yeoju County, Kyunggi Province, May 1999). In fact, it assumed an urban bias to assume that the culture of poverty—laziness, despair, and intemperance—was behind the slow economic growth in the countryside. Farmers in general had not given up on life before the NCM was introduced, as the slogans suggested. Rather, the problem was structural in nature.

After Park Chung-hee was assassinated in 1979, Chun Doo-hwan continued Park’s legacy as military dictator from 1979 to 1988. Chun Doo-hwan is infamous for committing atrocities, including the Gwangju Massacre. As many of you already know, Chun Doo-hwan passed away a few days ago at the age of 91.

Kishi remained a strong behind-the-scenes influence in Japan’s long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party until his death in 1987 at age 90. Kishi had a grandson, Shinzo Abe, who would also go on to become Prime Minister of Japan, and carry on the torch of unreformed Imperial Japanese ideology. Abe has expressed admiration for his grandfather Kishi, and was a special advisor to the group Nippon Kaigi,(Japan Conference), a powerful Japanese ultra-nationalist organization with a far-right extremist agenda which has many members in high positions in the Japanese government, including the current prime minister and former prime ministers.

Kishi’s legacy lives on in Nippon Kaigi, which claims that Imperial Japan should be lauded for liberating Asia from Western colonial powers, the Tokyo war crimes tribunals were illegitimate, and war crimes such as the Rape of Nanking in 1937 were exaggerated or fabricated. Showa nostalgia is a significant driving force in the agenda of Nippon Kaigi: amending the post-war constitution to make it easier for Japan to wage war, censoring the history textbooks to push historical revisionist and denialist content covering up Imperial Japanese war crimes and atrocities, restoring the moral education curriculum that was used in prewar and wartime Imperial Japan, and rejecting feminism, LGBT rights, and gender equality, among others. It is unclear to me whether then Japanese Prime Minister Abe, grandson of Kishi, had a meeting of minds with then South Korean President Park Geun-hye, daughter of Park Chung-hee, when they reached a ‘final and irreversible’ settlement on the comfort women issue. But this would be an interesting question for further exploration.

The censorship regime of the American occupation may have ended in 1952, but in its place rose a softer censorship regime centered on the Chrysanthemum taboo, and it served to put a damper on even the slightest criticism of the Japanese Emperor or the Imperial family in postwar Japan, so that Japanese media generally self-censored when it came to the Imperial family. This has resulted in a Japanese population that overwhelmingly (71%) has fond views of the Imperial family. The Japanese foreign ministry and the imperial household agency work hand in hand to enforce this taboo in various ways: raising official protests, pressuring publishers into withdrawing publications, pressuring newspapers into withdrawing advertisements, threatening and bullying journalists through extra-governmental ultra-nationalist groups, and preventing official records from being released. The experiences of author Ben Hills of a controversial biography of Crown Princess Masako illustrate all these tactics. Until relatively recently, most Japanese were not aware of the mental illness that Emperor Taisho had, because the records on Emperor Taisho were censored. The current head of the imperial household agency, Yasuhiko Nishimura, has ties to the ultra-nationalist Nippon Kaigi organization.

This soft censorship regime around the imperial family has expanded in recent years under ultra-nationalist leaders, including Shinzo Abe, to include many other topics, like criticism of the Japanese government in general and discussion of history. For example, the ultra-nationalists have succeeded in pressuring textbook publishers into releasing heavily censored history textbooks omitting or downplaying Imperial Japanese war crimes and atrocities. This has been done by weaponizing the textbook screening process performed by the government to reject any history textbook that do not follow the revisionist and denialist agenda. Also noteworthy are the horrific experiences of Uemura Takashi, who lost his job and whose family was endlessly harassed by ultra-nationalist groups because of his reporting on the comfort women issue. The soft censorship may extend onto the Internet. In web searches, it is difficult to find embarrassing quotes by Japanese war criminals like Tojo Hideki and Koiso Kuniaki. A German who Googles “Adolf Hitler Zitate” could find plenty of embarrassing quotes from Adolf Hitler demonstrating the craziness of his Nazi ideology. On the other hand, a Japanese who Googles “東条英機 名言” and “小磯国昭 名言” would mostly find neutral or flattering quotes from Tojo Hideki and Koiso Kuniaki, respectively.

This censorship has resulted in at least two major consequences. #1 This has dampened any national discussion about the nature of the Imperial Japanese ideological belief system, closely tied in with the Imperial family, that was the driving force of Imperial Japan through its colonial expansion and wars of conquest. #2 This has led to the rise of a Showa revivalist nostalgia (showa kaiki, 昭和回帰), or a nostalgia for the bygone days of prewar and wartime Imperial Japan, when Japanese subjects were supposedly noble, morally upright, and pure in heart.

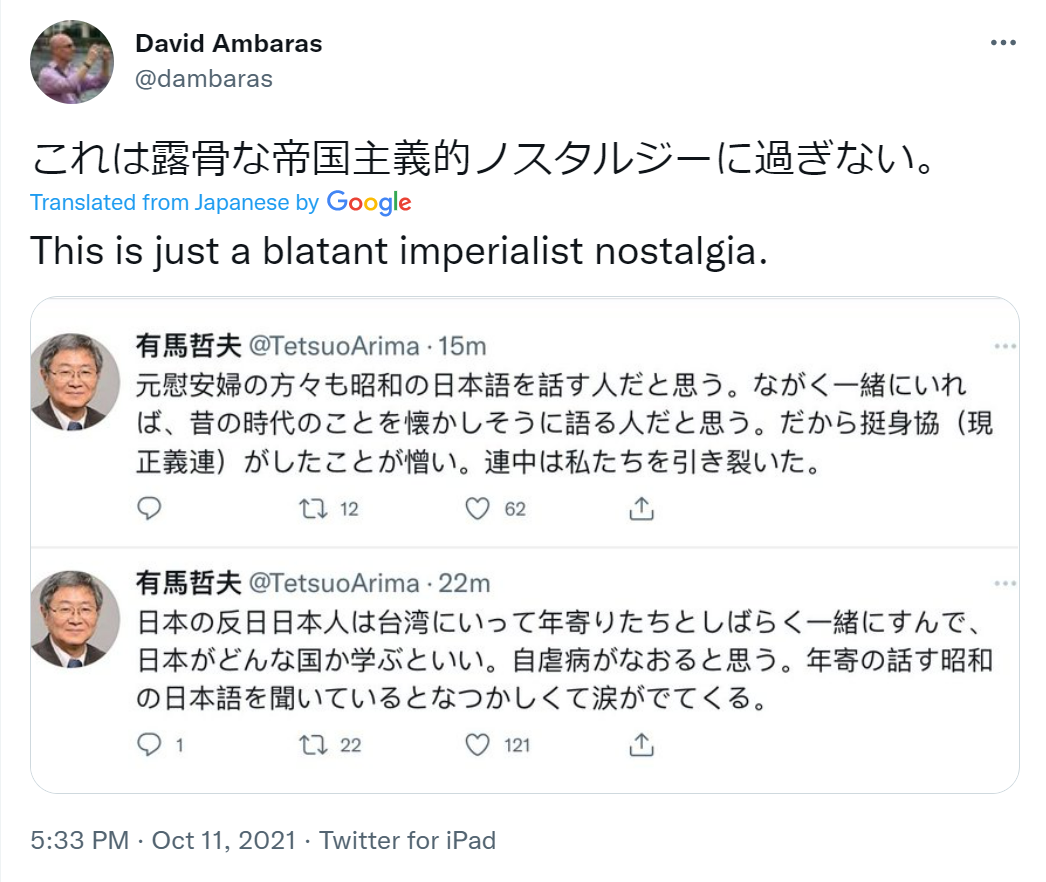

We can see this dangerous form of Showa revivalist nostalgia in Professor Tetsuo Arima, a Japanese historical revisionist and denialist at Waseda University who is notorious for asserting that the comfort women at Imperial Japanese comfort stations were willing prostitutes. He is just one of many denialists in a vast denialist network of academics, businessmen, and politicians that even reaches up to the top levels of the Japanese government (as explained in detail here by Professor Morris-Suzuki). His group of historical denialists on Twitter have consumed the lives of legitimate historians trying to fight them. One respected historian on the receiving end of many of Arima’s attacks, Amy Stanley, has called Arima her personal mini Donald Trump. David Ambaras, Professor of History at North Carolia State University, demonstrates two of Arima’s tweets:

有馬哲夫 on Twitter: “元慰安婦の方々も昭和の日本語を話す人だと思う。ながく一緒にいれば、昔の時代のことを懐かしそうに語る人だと思う。だから挺身協(現正義連)がしたことが憎い。連中は私たちを引き裂いた。” / Twitter Translation: “I think the former comfort women were also Japanese speakers of the Showa era. I think that, if you stayed and talked with them for a long time, they would talk nostalgically about the old times. That’s why I hate the Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance. They drove us apart.”

有馬哲夫 on Twitter: “日本の反日日本人は台湾にいって年寄りたちとしばらく一緒にすんで、日本がどんな国か学ぶといい。自虐病がなおると思う。年寄の話す昭和の日本語を聞いているとなつかしくて涙がでてくる。” / Twitter Translation: “Anti-Japan Japanese people should go to Taiwan and live with the elderly people there for a while, and learn what kind of a country Japan was. I think the self-deprecation would be cured this way. When I listen to the Japanese language of the Showa era spoken by elderly people, I feel nostalgic and I tear up.”

Arima’s Showa revivalist nostalgia leads him to venerate prewar and wartime Imperial Japan as a model that modern Japan should aspire to in reviving the religious death cult ideology centered on State Shintoism and Hakko Ichiu thought. In my previous post, I demonstrated how this line of thinking leads him to have a cognitive blind spot which prevents them from even entertaining the possibility that, maybe, the Imperial Japanese regime and military were less than honorable.

Linked to this Showa nostalgia is also the desire to restore the educational system to the way it was in prewar and wartime Imperial Japan. As alluded to earlier, nostalgia for the moral educational curriculum of prewar and wartime Imperial Japan has been a recurring talking point among right-wing Japanese politicians. For example, former Prime Minister Nakasone said the following (reproduced from 日本における保守主義の教育思想, The educational philosophy of conservatism in Japan):

戦後の教育は、どういう人間になるかという発想がなかったのはそのとおりですが、強いていえば、「蒸留水みたいな人間になれ」ということであるのかもしれない。(中略)私は現行憲法も教育基本法も、その制定の根源を尋ねれば、それは日本解体の一つの政策の所産とみています。「平和」「民主主義」「国際協調」「人権尊重」という立派な徳目を身につけた人間を育てようと書かれているが、日本民族の歴史や伝統、文化、あるいは家庭には言及せず、国家、あるいは共同体に正面から向き合ってはいない。つまり、(中略)それはブラジルでもアルゼンチンでも、韓国でも適応されうる。ようするに、「蒸留水みたいな人間を作れ」ということであって、立派な魂や背骨を持った日本人を育てようということではないのです。(中略)今や青少年のモラルの低下は覆いがたいものがあり、援助交際や学級崩壊という現象まで起きるようになった。(中略)これを治療するのは、文部省や教育改革国民会議だけの仕事ではなくて、総理大臣の仕事です。教育革命によって戦後教育の体系を創造的に破壊し、そこから新たな建設をしなければならない。

(my translation) It is true that post-war education was not based on the idea of what kind of person one should become, but if I had to put it another way, I would say that it may have been about “becoming like distilled water”. (…) If you ask me about the roots of the current Constitution and the Basic Education Law, I see them as the product of a policy of dismantling Japan. It says that we should raise people with the noble virtues of “peace,” “democracy,” “international cooperation,” and “respect for human rights,” but it does not refer to the history, traditions, and culture of the Japanese people, nor to the family, nor does it face the nation or the collective Japanese people head-on. (…) In other words, it could be applied to Brazil, Argentina, or Korea. In other words, the idea is to “make people like distilled water,” not to raise Japanese people with fine souls and backbones. (…) The decline in the morals of the youth has become unmistakable, and there are even phenomena such as prostitution and class disruptions. (…) It is not only the job of the Ministry of Education or the National Council for Educational Reform to cure this, but also that of the Prime Minister. The educational revolution must creatively destroy the postwar education system and build a new one from there.

An editorial from Toyo Keizai discusses the dangers of such a reconstructed educational curriculum:

国の価値観が強く反映された徳目の1つに、「国や郷土を愛する態度」がある。「道徳の教科化」の議論において特に話題に上る徳目だ。その中身は、「我が国や郷土の文化を大切にし、先人の努力を知り、国や郷土を愛する心をもつこと」とされる。

改憲の動きがいまだ盛んで、近隣国の動きも穏やかとは言えない昨今、有事がないとも限らない。これまでのように戦争は起きないと誰が言い切れるだろうか。「国や郷土を愛する心」の解釈もさまざまだろうが、もし戦争が始まれば、この道徳の教えによって、いまの若者たちが国家に「主体的に隷属する」可能性は大いにある。

そんな国をわれわれは望んでいるのだろうか。本当にそれでいいのだろうか。

軍国主義が徹底され、「聖戦だ 己れ殺して 国生かせ」といった戦時標語が跋扈(ばっこ)した戦時下の日本において、若者が何を思い、何に苦悩したのか、我々は知っておく必要がある。

(my translation) One of the virtues that strongly reflects national values is “love for one’s country and homeland”. This is one of the virtues that has come up for discussion in the debate over the introduction of moral education. One of the virtues strongly reflected in the new constitution is “love for one’s country and homeland”.

The movement to change the constitution is still active, and the movements of neighboring countries are not calm these days. Who can say that war will not occur as it has in the past? There may be different interpretations of “love for country and homeland,” but if war breaks out, there is a great possibility that today’s young people will be “actively subjugated” to the nation by this moral teaching.

Do we really want such a country? Is that really what we want?

We need to know what young people thought and suffered in wartime Japan, when militarism was thoroughly practiced and wartime slogans such as “Holy War! Kill Yourself and Let the Nation Live!” abounded.

Japanese activists opposed to Showa revivalist nostalgia have resisted in various ways over the years, as covered in this excellent paper. However, the overwhelming institutional inertia of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which in turn is ruled by the Nippon Kaigi organization, and the soft censorship apparatus of the Japanese state have made effective opposition a very difficult uphill battle. I have not done extensive research on the conservative forces of South Korea, but from the fact that Park Geun-hye, the daughter of Park Chung-hee, managed to become President of South Korea, it seems to me that extreme right-wing elements are a significant force in South Korea. There are also many monuments and memorials to Park Chung-hee in South Korea, suggesting that perhaps his support base among South Koreans is still significant.

I found this interesting Youtube video (no English, just Korean with Japanese subtitles) showing an 87-year-old Korean man who recounts his happy childhood experiences going to Japanese schools in Japan-occupied Korea. That means he was 11 years old in 1945 when World War II ended and Korea was liberated. While I’m glad that he never had the chance to experience the worst of Japanese colonial rule of Korea, this old man goes off the rails when he complains about the current state of modern South Korean society, and nostalgically says that things would have been better off if Japan had remained in control of Korea. I charitably attribute his views to ignorance – if he had better knowledge of the policies of the Imperial Japanese regime in occupied Korea, perhaps he would have changed his views. (The Korean Youtuber who posted this video is also interesting – he appears to align himself with the Japanese ultra-nationalists in almost every view, including views on comfort women. He speaks almost exclusively in Korean with Japanese subtitles in his videos, but the viewers’ comments are almost all in Japanese. That means his Korean language videos have an almost exclusively Japanese audience.)

It’s very heartbreaking to see so many people being misled by far-right extremists with nefarious agendas. There are legitimate historians like Amy Stanley, Sayaka Chatani, David Ambaras, and Paula Curtis who are already putting themselves out on social media fighting historical misinformation. What else can we do to help them out?

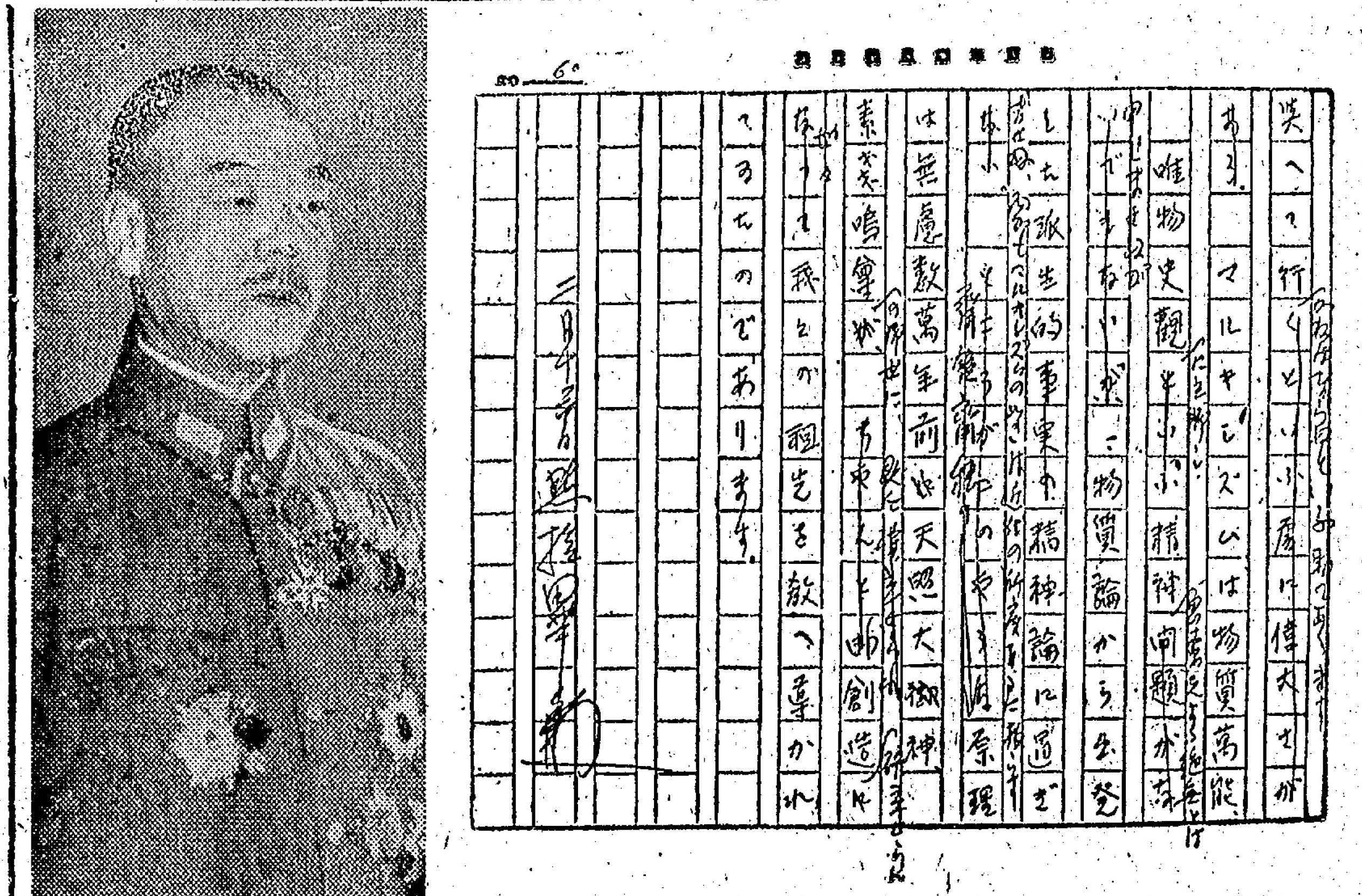

As I reiterate here, I believe that one way to help out is to make wartime newspaper issues of Keijo Nippo (Gyeongseong Ilbo) of Japan-occupied Korea more accessible through transcription and translation. What makes Keijo Nippo special over other Japanese-language newspapers of this time period is the fact that they have such good coverage of the imperialization process that the Japanese colonial government applied on the Korean people. Thus, we have very good descriptions of Imperial Japan’s educational policies and their execution in forcibly assimilating the Koreans into “true Imperial subjects” by not only imposing the Japanese language, but also by imposing the Imperial Japanese ideology on them. Publicizing these articles, which expose the intolerant, fanatical, militaristic, coercive, and inhumane nature of educational policies under Imperial Japan, could go a long way in breaking the romanticization of the Imperial Japanese education system, including its moral educational curriculum, as a model to aspire to. The cringe moments (“whoa, that’s messed up”, “wait, WTF?”) that are induced by reading the most embarrassing articles from Keijo Nippo could plant the seeds of doubt, which are important in deprogramming cult members.

So far, I have been perusing the Keijo Nippo newspaper archives that an anonymous benefactor uploaded to Internet Archive last month. Unfortunately, these archives have a number of shortcomings. I suspect that the newspaper archives were digitized microfiche film, which is a problem because the quality of the scans is terrible for many issues, making them illegible or very difficult to read. I would often need to do some “smudge reading”, playing a game of Scrabble as I guess what letters the smudges might represent. The issues published in the latter half of 1944 are mostly illegible, aside from the headlines, due to the deterioration of the microfiche slides. The issues from 1945 are completely missing. That is very unfortunate, since the fanaticism of the Imperial Japanese regime really ramped up by late 1944 and 1945, and we miss out on a lot of material that could embarrass the Japanese historical revisionists.

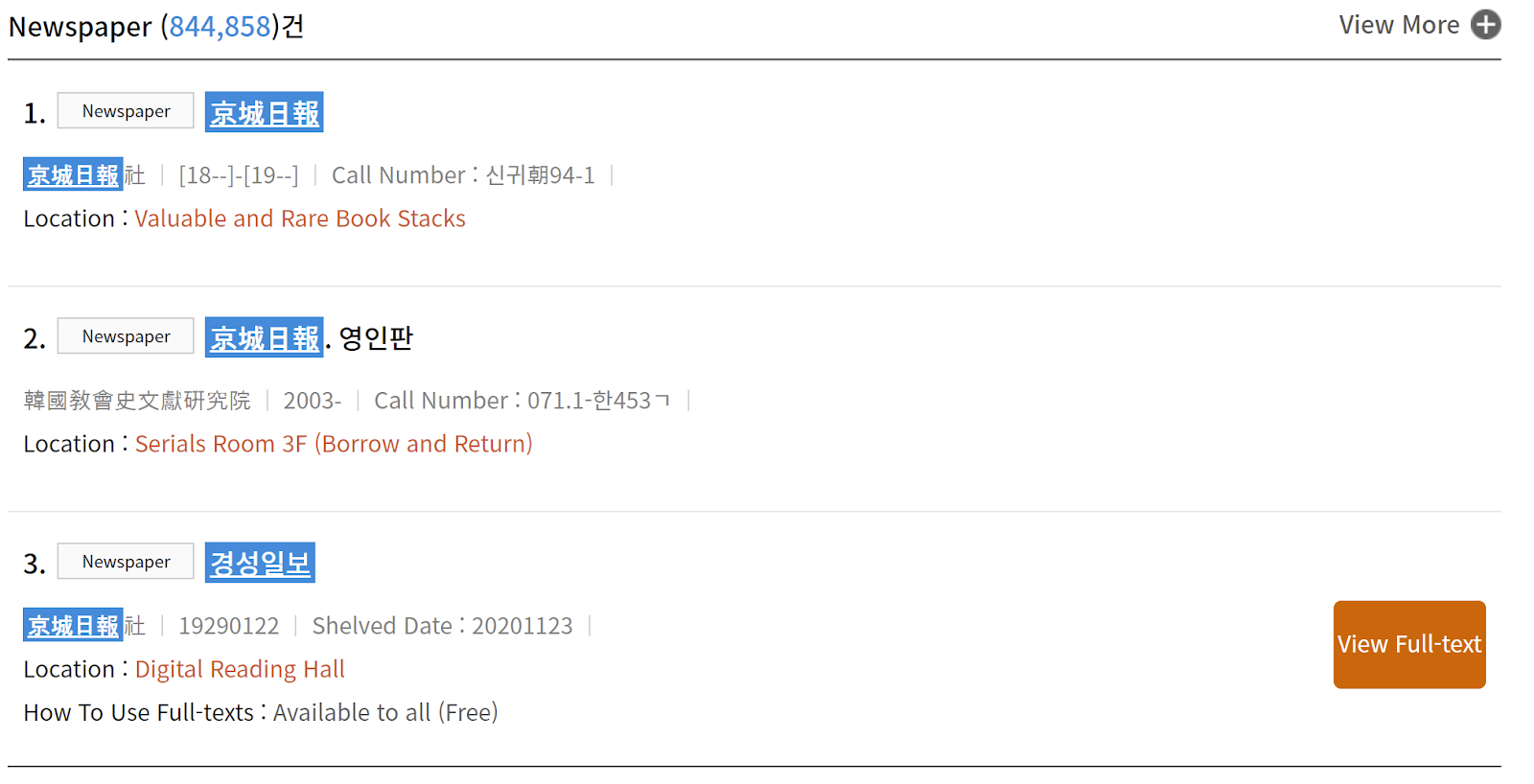

This prompted me to search if there were other archives of Keijo Nippo that were not microfiche. I checked the Tokyo National Diet Library website, and there were none. I checked the National Library of Korea website and found to my surprise that some digital copies of Keijo Nippo from 1926 to 1930 were available online in very high-quality resolution. But the viewer app does not let you screen capture any of the images. Then I found that the physical copies of Keijo Nippo from September 1915 to December 1945 were available, somehow surviving the ravages of the Korean War. My wish is that the National Library of Korea would digitize the key issues of Keijo Nippo from 1944 and 1945 and make them available online without screen capture restrictions, but I know that this is a longshot.

Search results at National Library of Korea for “Kyeongseong Ilbo”

Another longshot idea is to personally ask former Princess Mako to give her voice to denounce the historical denialists who are using the Emperor’s name to cover up Imperial Japanese war crimes and atrocities. Two years ago, the Comfort Women Justice Coalition released a Letter to the Emperor tactfully asking the Japanese Emperor for an apology. Personally, I think it was unrealistic to expect even pacifist-leaning Emperor Akihito to speak up for comfort women, since he was not constitutionally allowed to speak up politically. In fact, they are so sensitive about this that the imperial household agency got into trouble for commenting that the Emperor voiced his concerns about the spread of the coronavirus. On the other hand, former Princess Mako just married a commoner and is no longer a part of the Imperial family, so she has more freedom to speak out. She now lives in New York and is looking for a job in the art world, so if any New Yorkers on this subreddit happen to encounter her, please be sure to remind her that she could potentially make a big positive impact on the world with her words.

So, longshot ideas aside, I will do my little part with the resources that I have right now to continue my slow translation project on the wartime Keijo Nippo newspaper issues, focusing on articles that touch on the educational policies of Imperial Japan, embarrassing statements from war leaders, and the treatment of Koreans. After listening to suggestions from fellow Redditors, I set up this blog site to archive the transcriptions and translations of news articles that I have posted on Reddit so far. I’ve been busy with work and family obligations in recent days, but I hope to continue this project as long as I find the free time to do so.