Imperial Japanese news staff departing Korea wrote last words celebrating the ‘Young Korea’ as a ‘joyous uprising’, praising Kimchi, saying goodbyes to Korean collaborator writers, baring ‘a heart full of desolation’, mourning a daughter’s death, criticizing war leaders… (Nov. 1, 1945)

2024-01-23

413

2550

This is the second part of a two-part series. The first part is posted here.

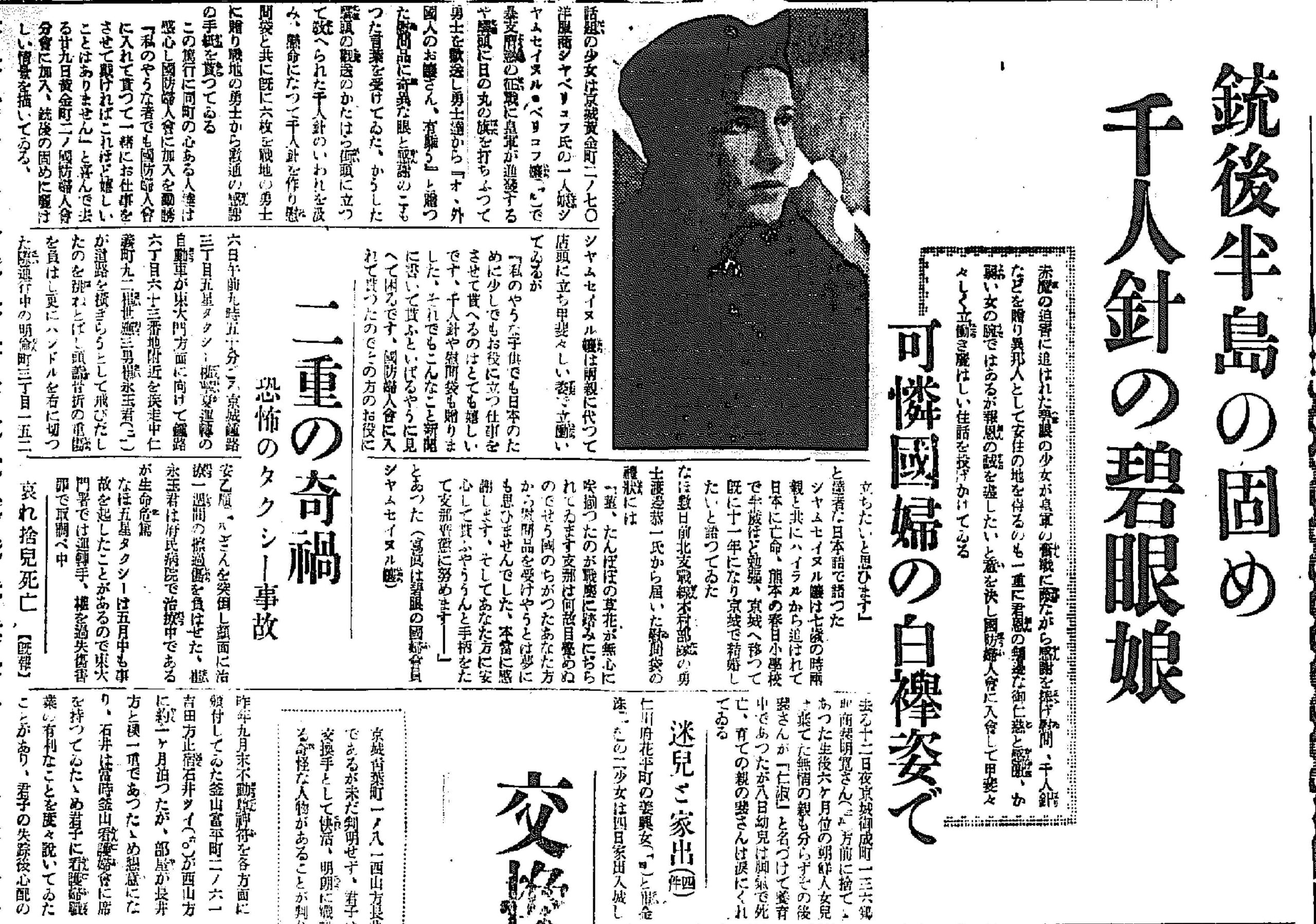

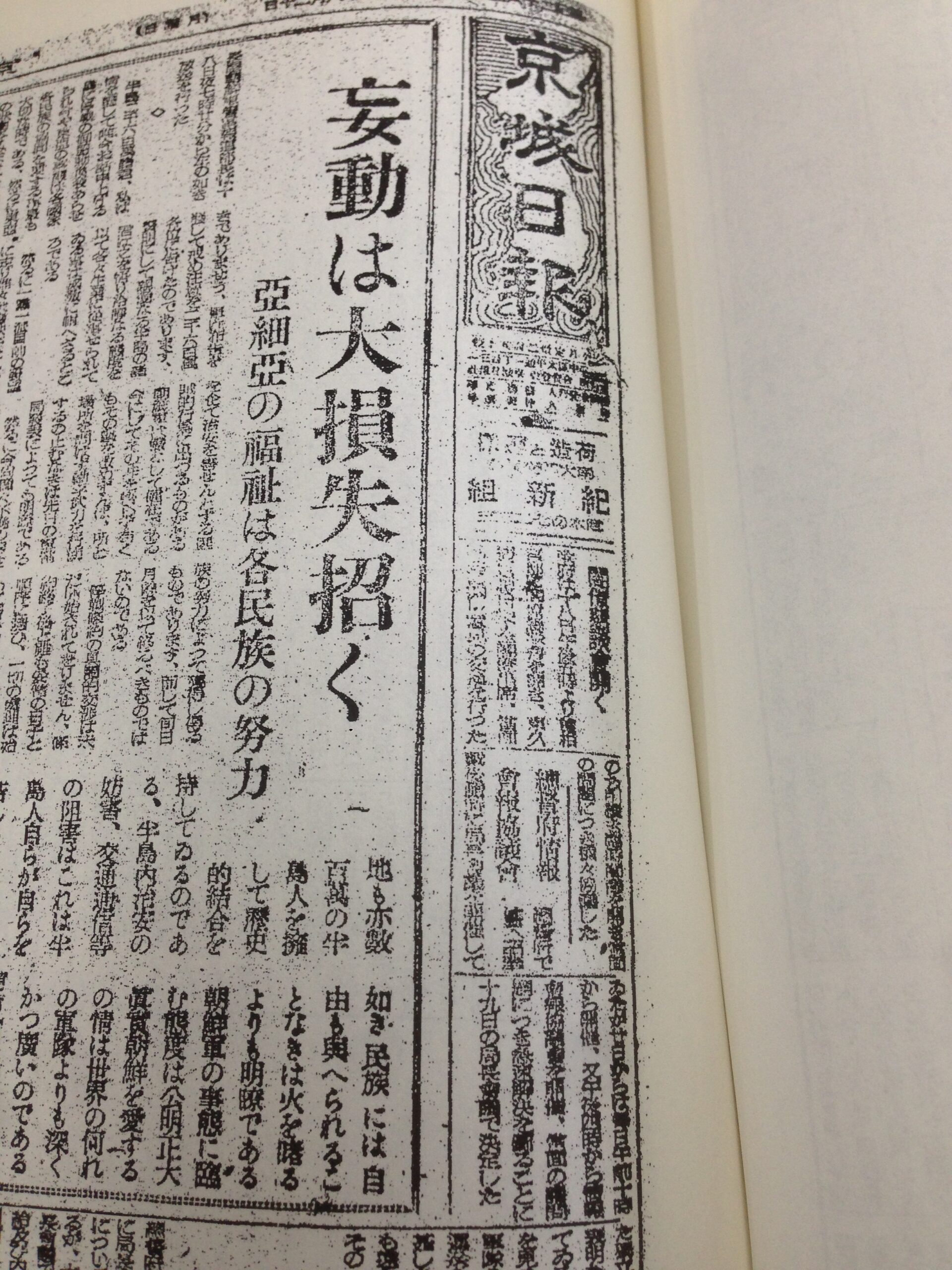

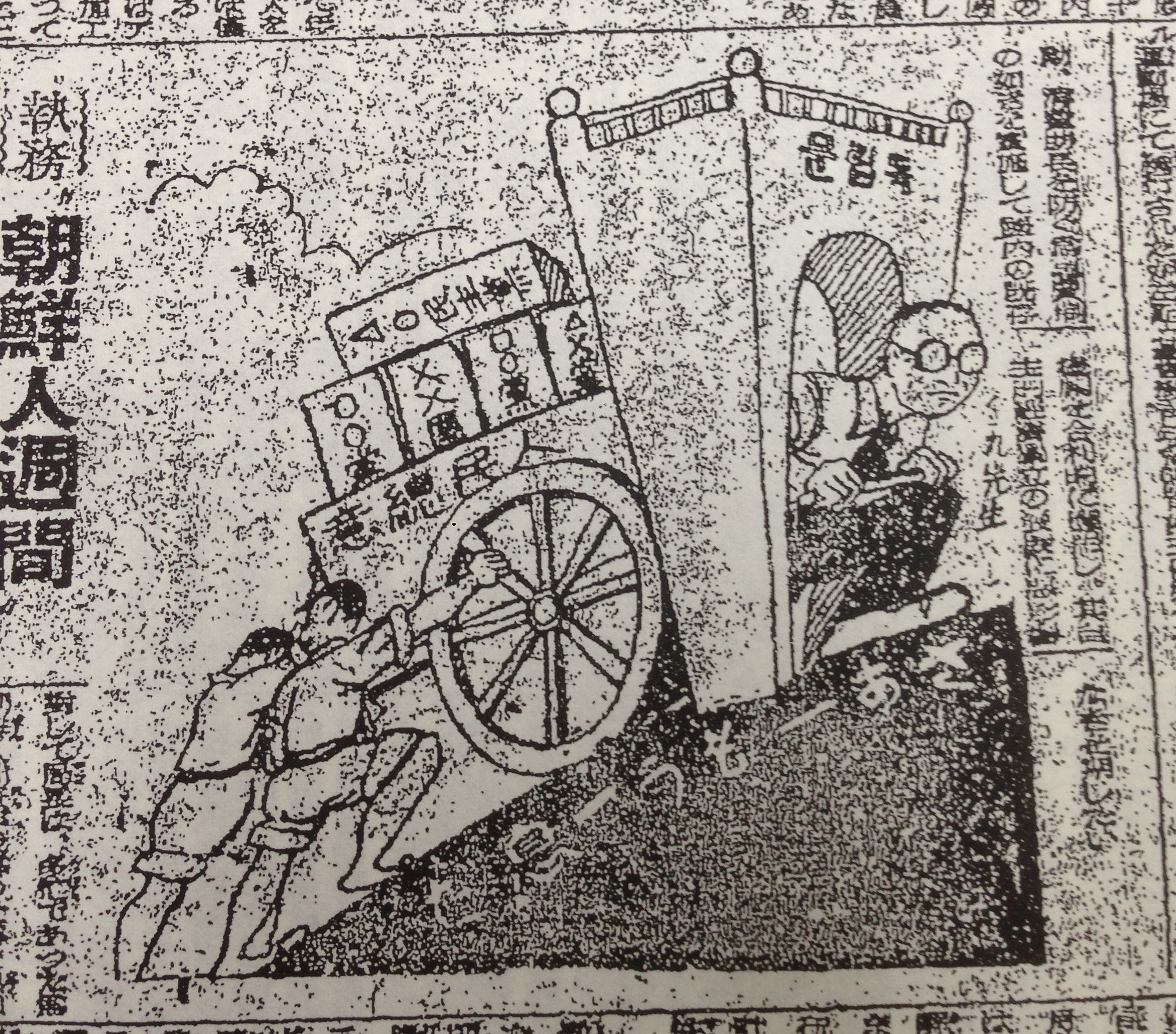

The following is content from a Seoul newspaper published on November 1, 1945, two and a half months after Japan’s surrender in World War II and the liberation of Korea. Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo), the colonial era newspaper that had served as the main propaganda newspaper for the whole of colonial Korea from 1909 to 1945, was still publishing in Japanese as the national newspaper of Korea. The ethnic Japanese staff managed against all odds to retain control over the newspaper during those two and a half months, until they were finally forced to relinquish control to the Korean employees. These Koreans independence activists took over and subsequently continued the publication of this newspaper in Japanese with an avowed Korean nationalist editorial stance from November 2nd until December 11th, 1945.

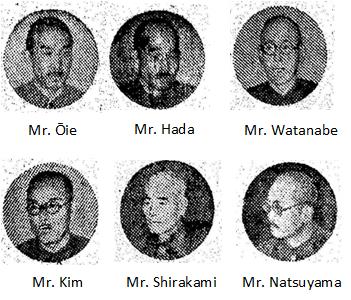

However, before the ethnic Japanese staff was forced to leave, they were allowed to publish one last issue, dated November 1st, 1945, with the very last page dedicated to farewell messages that they wrote to the Korean people as a memento, in which they eloquently express their sad and conflicted thoughts and feelings. Unfortunately, I found this last page in poor condition with big ink blots, gashes, and faded text, so it was very difficult to read them. Nonetheless, due to the compelling content of these long forgotten messages, I decided it was worth spending some time deciphering them as much as I could. There were seven different essays on this page with six different authors. Due to their sheer length, I shared two of the essays in the first part of this series, and I am sharing the five remaining essays in this post as I unlock this long forgotten time capsule.

There is a lot to unpack in these five essays, but since an in-depth analysis of this cross-section of the post-war Japanese psyche would probably require a dissertation, I will mostly let the words of the authors speak for themselves with some Wikipedia links added for convenience. But I think it will be fair to say that the thoughts and feelings of these Imperial Japanese news editors are extremely complex and defy any simple characterization. So, I’ll just comment on a few notable things about these essays.

One of the essays bids farewell to the Korean writers of the Korean Literary Association, a puppet of the colonial regime. The Korean Literary Association was founded in 1939 to nurture Korean writers to serve the colonial regime. The association encompassed both ethnic Korean writers who wrote in Korean and Japanese and ethnic Japanese writers who were residents of Korea and wrote in Japanese, and the works of both groups were considered to be ‘Korean literature’, regardless of how different their cultures and perspectives may have been. In this way, Korean literature of this era became heavily politicized to serve the political interests of Imperial Japan. The association published a literary periodical that was published in both Japanese and Korean, but by May 1942, the Korean language edition was discontinued in the name of ‘Imperialization’ and ‘Japanese-Korean unification’. In an earlier post, I covered the propaganda writings of three of these Korean writers: Yu Jin-oh (유진오/兪鎮午, 1906~1987), Choi Jae-seo (최재서/崔載瑞, 1908~1964), and Lee Seok-hoon (이석훈/李石薫, 1907~?).

In the postwar era, the three members’ lives took very different courses. Yu Jin-oh became one the early drafters of the South Korean Constitution, worked as a legal scholar and as a prominent conservative politician in South Korea for many years until his death in 1987. Choi Jae-seo continued his academic activities teaching English literature at South Korean universities until his death in 1964. Lee Seok-hoon was arrested by the North Korean People’s Army at the outbreak of the Korean War in July 1950, and his whereabouts are unknown to this day.

Another thing I noticed was the author of one of the essays: Katō Manji, who was born in 1890 and died in 1980. He describes himself as being the chief of the organization department of Keijo Nippo from 1942 to 1945. Doing a quick online search, I learned that, according to a 2008 Asahi Shimbun article, in at least 1941 and 1942, he was also working at the organization department of Asahi Shimbun newspaper in mainland Japan. His surviving family members provided some personal artefacts to Asahi Shimbun, which apparently included reams of directives from the military censors telling him what he was not allowed to publish. For example, one of the rules was “Don’t use the word ‘white people’ (白人)”. This suggests that the chief of the organization department was in charge of making sure that the military censor’s directives were being followed by the newspaper staff.

This post is a continuation of my ongoing exploration of the old newspaper archives from 1945 Korea that I checked out and photographed at the National Library of Korea in September 2023.

[Translation]

Ten Years of Living in Seoul: Recalling Some of My Memories

By Terada Ei

When I look back at my ten years of life in Korea, various memories naturally come flooding back. Especially for me, it is inevitable that I will feel deeply moved, since I spent one-third of my newspaper career here.

At Keijo Nippo, I spent the longest time in the Arts and Culture Department. Because of this, I became quite close to many Korean cultural figures, which I consider an unexpected but valuable gain. Although I was known as a bit of a sharp-tongued person, I do not recall making any enemies, which is my most significant impression from my life in Korea. It is regrettable that I cannot bid farewell in person to each of these individuals, but even if I don’t address each of them by name, I believe that in their hearts, there lies a friendship that will recall me from time to time.

My memories of the time when the so-called Korean Literary Association was formed are particularly profound. In the words that we used back then, Japanese and Korean literati came together as one to move forward. However, among my comrades of that time, some foresaw the inevitability of air raids in Korea and promptly evacuated to mainland Japan, while others quickly disappeared to Tokyo as soon as the situation worsened. When you consider that those were our leaders at that time, and that they were Japanese people, it goes to show that a person’s true worth is revealed in times of crisis. I vividly remember traveling to 24 cities throughout Korea to give lectures as part of the so-called New System Movement during the Literary Association days. After the Literary Association became the Literary Patriotic Society, I became somewhat estranged from the scene due to the situation within the newspaper office at the time and the aftermath of an illness.

It is with reluctance that I speak of personal matters, but I lost my only daughter in Seoul. She had always been frail since birth, but she had never gotten sick even once since coming to Korea. After graduating from girls’ school, she had become healthy enough to volunteer to assist with the Imperial Navy’s work. However, she fell ill with a mild case of bronchitis, but after four days in bed, she passed away unexpectedly in the early hours of December 29. The doctor who saw her then was both the first and last doctor that she saw since coming to Seoul. She was twenty-three when she passed away.

What I gained from my time in Korea are the cherished memories of the many friends that I made, and the only thing that I lost was my hope in life, which I lost with the passing of my daughter.

My wife and I will soon leave Seoul, carrying two backpacks and an urn of ashes. It is difficult to deny that our hearts are filled with a mix of joy and sorrow, a tumult of various emotions.

Farewell, Korea. Farewell, Seoul, and farewell, my friends. Please accept this as my last goodbye in print. (October 31, 1945)

The Creation of a New Culture

By Nakaho Sei

I recall the day I first met General Arnold of the military government. The scene at the military government office, with its Western-style white chalk building, the Oriental-style building in the backyard with its predominantly red colors reminiscent of Beijing’s Forbidden City, the American soldiers in khaki uniforms, and the crowd of Koreans in white traditional attire at the gate, formed a unique and unforgettable image in my eyes. From behind this scene, I could see the faint white smoke of burned documents rising into the sky. It felt like a symbol of the culture of tomorrow’s Korea.

Looking back, it occurs to me that, whether it be Confucianism, religion, or Oriental music, many elements that added brilliance to Japanese culture from ancient to medieval times came from the Asian continent. However, it was Korea that played the crucial role of being a “bridge” connecting the Asian continent and Japan. Indeed, it may be said that, rather than being a bridge, Korea cultivated many of the ideas born in China and India before passing them on to Japan.

Buddhism is an excellent example of this. Confucianism, especially Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism, was greatly developed in Korea by great philosophers like Yi Hwang. The remarkable flourishing of Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism in Japan during the Tokugawa era owed much to Korean Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism. If it is permissible to say that Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism was an ideological driving force of the Meiji Restoration, then the distant roots of the Meiji Restoration would have to be sought in Korea.

The world, especially in its entirety, has been ravaged by war and will be preoccupied with reconstruction efforts without much time for reflection. In East Asia, Korea suffered the least damage from bombings. From this perspective, Korea is now in a position to be a major nursery and source for the rebuilding of Greater East Asian culture… Korea is blessed with the opportunity to leave a significant mark on the cultural history of East Asia as a creator of culture.

From a geopolitical standpoint, there are various views about the Korean peninsula. However, looking at the map, Korea lies between China and Russia on the Asian continent, facing Japan and the United States across the sea. Korea should combine and refine the cultures of these neighboring countries to construct a new culture, an endeavor that must achieve significant results. Moreover, by nurturing Korea’s inherent culture, such as that of the Baekje and Silla kingdoms, we can look forward to the growth of an even better new culture. (October 31)

Through the Newspaper Pages

By Katō Manji

The desperate struggles of the defeated nations, beginning with the establishment of the Badoglio government in Italy and the subsequent occupation by British and American forces, and then spreading to France and the smaller Balkan countries, were tragic to the extreme. These stories, transmitted via foreign telegram, were reported in Japanese newspapers, though only in a limited fashion. Japanese wartime leaders also used these real-life examples to teach the lesson that we must “win at all costs.”

However, since August 15, Japan, as a “defeated nation,” a label it has borne for the first time since its founding, has faced an increasingly severe and cold reality day by day.

As the chief of the organization department (editor) of Keijo Nippo, I have been in Korea for about three years, starting around the time when the reports of the Guadalcanal campaign began. Since then, amidst the continuously deteriorating circumstances up to this day, I have devoted my modest efforts to newspaper production and publishing. Looking back on this, there are countless things I want to write and say, but my pen is heavy, and progress is slow.

Now, Korea is moving away from Japanese rule and gathering collective wisdom for the construction of a new nation. It is truly a moment of joyous uprising. I can’t help but celebrate for the young Korea. In contrast, we are gasping under the bitter dregs of defeat, returning to a chaotic and tumultuous Japan, sinking into the depths of agony. But let us not forget about “rebuilding Japan” and the task of rising from the depths, overcoming a thousand difficulties.

Due to my job, I never stepped out of the editorial office, let alone had the chance to do any inspections within Korea or make many influential Korean acquaintances. However, I am satisfied and take joy in saying goodbye, having known about 400,000 readers through the newspaper pages for about three years.

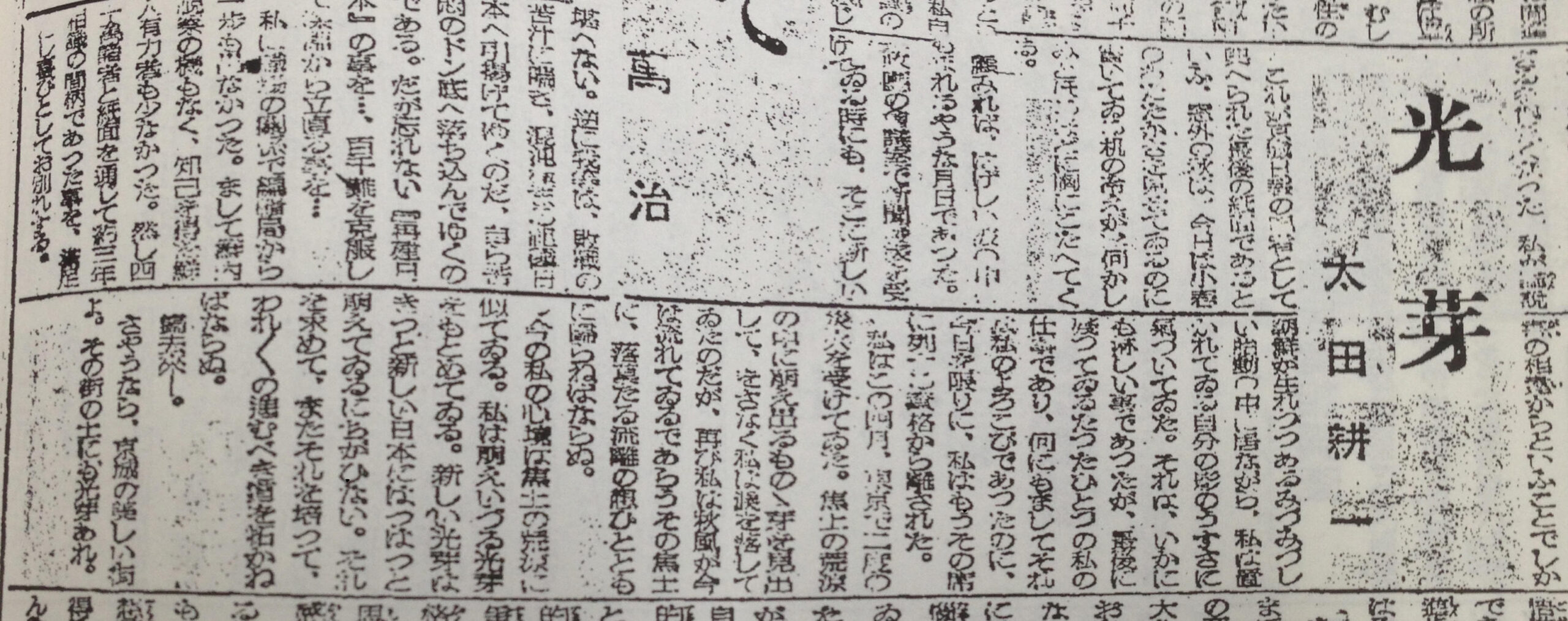

Light Sprouts

By Ōta Kōichi

The coldness of the desk, resonating with the warmth of the Indian summer outside the window, strikes my heart, reminding me that this is my last page as a reporter for Keijo Nippo.

Looking back, these days have been tumultuous, like being tossed in fierce waves. Even while attending press conferences at the military government office and witnessing the fresh stirrings of a new Korea being born, I was aware of the thinness of my own shadow. It was a lonely realization, but this was my last remaining duty and my greatest joy. Yet, today marks the end of my qualification to sit in that seat.

This April, I experienced two disastrous firestorms in Tokyo. Seeing sprouts emerging from the desolate burnt earth, I found myself shedding tears. Now, I must return to that scorched land, with a heart full of desolation and wandering thoughts, where the autumn wind now blows.

My current state of mind is like that desolate scorched earth. I am seeking sprouting light. I am certain that new sprouts of light are vigorously emerging in a new Japan. I must seek them out and nurture them to pave the way that we should follow.

Let’s go home. Farewell, beautiful city of Seoul. May there be light sprouts in your soil too.

My Words

By Ōnuma Chiyo

If my friend waiting in a thatched hut in Shinano asks me what I learned from Korea, I would spontaneously reply, “I learned the taste of kimchi.”

My time in Korea was spent in a short period suffering from catarrh, waiting to return to work and being overwhelmed by daily life. I had no leisure to explore the local historical sites, since I spent that time convalescing while reading the meager literature available.

Therefore, my life in this land felt empty, but one unforgettable thing that remained with me was the taste of kimchi. As I gradually became accustomed to its complex and varied flavors, it paralleled how I slowly assimilated into life in Korea. During that time, I became indifferent to the copious yellow dust and the pungent smell of garlic. The scent of the clay soil conveyed a sense of romance. The intense taste of kimchi served as a pleasant sedative to the intense emotions within me, leaving a lasting imprint on me due to its strength.

Though my time here was just over a year, I encountered an unfathomable rush of history. In my heart, which seeks to step into the world of contemplation, this significant event also provided a lesson that could be considered great in some sense.

In the remainder of my life, my heart will probably cherish the taste of kimchi with nostalgia, and hold an unbearable longing for the life I lived in this land for just over a year.

[Transcription]

京城日報 1945年11月1日

京城生活十年

=思い出の幾つかを拾う=

寺田 瑛

朝鮮生活十年を顧みると、さまざまの思い出が湧き出るのも無理はない。殊に、私としては私の新聞人生活の三分の一を費やした地である。感慨なからんとしてなき能わざる所以である。

京城日報では学芸部に一番永くいた。そんな関係で、朝鮮の文化人とも相当近づきになり、これは寧ろ意外な収穫であったといい得る。一面に毒舌家だといわれながらも、私は敵を持ったという思い出を一つも持たない。朝鮮生活に於ける私の最も大きい感銘である。今しみじみと離別の言葉をそれ等個々の人たちに捧げ得ないのは残念であるが、特にその名を挙げないにしても、それ等友人自身の胸の中には、私というものを時に応じて回想してくれる友情があるであろう。

いわゆる朝鮮文人協会というものが結成されて、当時の言葉でいえば内鮮、今の表現なら日鮮の文人が打って一丸となって進むことになった頃の思い出は特に深い。だがあの頃の同志の中に、朝鮮にも空襲必至と見抜いて逸早く内地へ引き揚げて行った人もあるし、今度の事態になるや否や、一目散に東京へ姿を消した人もあり、それが当時のリーダー格の人たちであり、また日本人であったことを思うと、やはりイザという時にこそ、その人の真価はわかるということを教えられる。文人協会時代の思い出の中でもいわゆる新体制運動をひっさげて全鮮二十四都市を分担して講演に出たことが印象に蘇える。文人協会が文人報国会になってからは、私は当時の社内事情と病後とのためについ疎遠になってしまった。

個人のことについて述べるのは憚られるが、私がひとり娘を喪ったのも京城である。生来虚弱の子でありながら、朝鮮へ来てからは一度も病気をしたことがなく、女学校卒業後は、逆に自分から進んで海軍の方の仕事を手伝う程の健康になっていたのに、かりそめの気管支炎に臥床四日、十二月二十九日の未明に呆気なく死んでしまった。しかもその時医者に診てもらったのが、彼女が京城へ来て医者にかかった最初であり、最後でもあったのだ。享年二十三であった。

私が朝鮮へ来て得たものは、数多い友人をめぐる懐かしい思い出であり、私が京城へ来て失ったものは、ただこの娘の死をめぐる人生への希望である。

私たち夫妻は、二つのリュックサックと一つの遺骨箱を携えて、不日京城を去るのであるが、互いの胸には喜悲を織りまぜた、さまざまの感情のみが去来すること否み難い。

さらば、朝鮮よ。京城よ。そして友よ。これが私の活字として残す最後の別れであることを受けられたい。(2605-10-31)

新文化の創造

中保 生

はじめてアーノルド軍政長官に会った日である。軍政庁のあの白亜の洋風建築と其の裏庭の丁度北京の紫金城を想わせるような赤い色彩の多い東洋風建築と、褐色の軍服を着ている米国の軍人と、庁舎の門前に群れている白衣の朝鮮服姿とが渾然一つに綜合されて僕の瞳に曾てない不思議な映像を描くのであった。而もそうした映像の陰からは焼いた書類の灰白い煙が漸く大空へ立ち昇っているのである。僕はふと明日の朝鮮文化の象徴を見たような心地がした。

回顧すれば、儒学にせよ、教学にせよ、或は東洋音楽にせよ、凡そ古代中世にわたる日本文化に絢爛たる光彩を添えたものの多くは大陸から渡ったのである。然し、常に其の大陸と日本とをつなぐ『橋』たる使命を果たしたのが、実に朝鮮であった。いな、『橋』というより、支那や印度に産声を挙げたものをここで培養して日本へ手渡したと解すべきものが少なくない。

仏教なぞはまさしく其の最もよい例であった。儒教にしても特に朱子学の如きは李退渓等の大哲学者によってここに大成されたのである。日本の朱子学が徳川時代あのようにすばらしい興隆を見るに至ったのも朝鮮の朱子学に負うところ頗る大なるものがあった。大義名分を説く朱子学が若しも明治維新の思想的原動力であったということにして許されるならば、おそらく明治維新の遠い淵源を朝鮮に求めなくてはならにであろう。

世界は、此の全域上は、その戦火に禍され、今後も復興工作のため十分思索の余裕をもたないが、東亜に於いて爆弾の被害の最も少なかったのが即ち朝鮮である。そうした点からいえば、朝鮮こそ、今や大東亜文化再建の一大苗床たり一大淵藪となるべき環境にあるといわなくてはならい。[illegible]自ら大成者として、東亜の文化史上に偉なる実跡を印すべき機運に恵まれたのである。

地政学的に半島を観ると、そこには幾多の見解もある。然しながら、地図を按ずれば、大陸に於いて支那とロシアとに接し海を隔てては日本と米国とに相対しつつあり、之等隣国の文化を綜合し、揚棄してここに新文化を建設せんとする企図だけでも相当の成果を収めなくてはならない。況んや、百済文化、新羅文化等は兎角あれ朝鮮本然の文化を増育することによって、更によき新文化の成長を待望することが出来るであろう。(10-31)

紙面を通じて

加藤万治

敗戦国民の惨憺なる奮闘の姿は、イタリアにバトリオ政権ができてから米英軍の進駐に始まり、更にフランス、バルカンの諸小国に拡がり、当時、外電により伝えられた悲惨極まる諸諸相は、日本新聞も細々と掲載したのである。日本の戦導者もこれ等の実相を引例して『断じて勝たねばならぬ』事を訓えた。

然るに、八月十五日以降、日本国には肇国以来始めて喫した『戦敗国』という烙印は、余りにも冷厳であり、日一日とその深刻度は加重して来たのである。

私は、京日の整理部長(編輯)として来鮮約三年、ガダルカナル戦の奏報が発表されだした頃からである。以来今日までの悪化一途の諸情勢下にあって、新聞製作や、出版の事に微力を尽くして来た。その一つについて顧みる時、書きたい事、言いたい事は山ほどもあるが、ペン重くして進まない。

いま朝鮮は日本の統治を離れ、新国家建設のため幾多の衆智が凝集されている。洵に歓喜湧起である。若き朝鮮のため慶祝堪えない。逆に我等は、敗戦の苦汁に喘ぎ、混沌極まる祖国日本へ引き揚げてゆくのだ。自ら苦悶のどん底へ落ち込んでゆくのである。だが忘れない、『再建日本』の事を。百千難を克服して深淵から立ち直る事を。

私は職場の関係で編集局から一歩も出なかった。まして鮮内視察の機もなく、知己を得た鮮人有力者も少なかった。然し四十万読者と紙面を通じて約三年相識の間柄であった事を、満足とし喜びとしてお別れをする。

光芽

太田耕一

これが京城日報の記者として与えられた最後の紙面であるという、窓外の秋は、今日は小春のあたたかさを見せているのに響いている机の冷えが、何かしみとおるほどに胸にこたえてくる。

顧みれば、はげしい波の中にもまれるような月日であった。軍政庁の会議室で新聞発表を受けている時にも、そこに新しい朝鮮が生まれつつあるみずみずしい胎動の中に居ながら、私は置かれている自分の影のうすさに気づいていた。それは、いかにも淋しい事であったが、最後に残っているたったひとつの私の仕事であり、何にもましてそれは私のよろこびであったのに、今日を限りに、私はもうその席に列する資格から離された。

私はこの四月、東京で二度の災火を受けていた。焦土の荒涼の中に萌え出るものの芽を見出して、おさなく私は涙を落していたのだが、再び私は秋風が今は流れているであろうその焦土に、落莫たる流離の思いとともに帰らねばならぬ。

今の私の心境は焦土の荒涼に似ている。私は萌えいずる光芽をもとめている。新しい光芽はきっと新しい日本にはっはっと萌えているにちがいない。それを求めて、またそれを培って、われわれの進むべき道を拓かねばならぬ。

帰去来―。

さようなら、京城の美しい街よ。その街の土にも光芽あれ。

私の言葉

大沼千代

信濃の草庵に待つ友から『朝鮮から何をまなんで来たか』と訊かれたら、私は無雑作に『キムチの味を覚えて来た』と答えるであろう。

短日月の潟留でそして仕事を待ち、生活、追われいた私には地方の古蹟を尋ねる余暇もなく、とぼしい文献の上でわずかにそれを癒やしいたといって好い。

それ故に寥々たる私の此の地での生活ではあったが、ただ一つキムチの味だけには忘れがたないものを残された。複雑多岐なその味に私が少しづつ馴染んで行ったことは、同時にこの朝鮮での生活に、私が次第に溶け込んで行ったのと同じ観を持つのである。そのような頃、私は夥しい黄塵や、大蒜の悪臭にいつか不感性になっていた。そうして埴土の香りは浪漫をつたえた。キムチの持つ強烈な味は、私のうちなる劇しいものに、快い鎮静剤の役割をも果たした。そしてその強烈さの故に私のうちに完全に烙印をのこしたのである。

一年余の歳月ではあったが、あり得ぬ歴史の怱忙にも遭遇した。観照の世界に踏み入ろうとしている私の心では、またこの一大事も或る意味では偉大といって好い程の訓戒を与えたのであった。

そこばくの私の余生において、おそらく私の心は、キムチの味になつかしさを抱き、一年余の此の地の生活に堪えがたい郷愁を持つのであろう。