Young Korean teachers teach children the ‘will to fight and destroy the U.S. and Britain’ and the Imperial Way of Labor where ‘every stalk of grass and every tree’ is connected to the Japanese nation and everything in the villages is ‘all solely dedicated to the Emperor’ (Sosa, 1943)

This is a ‘feel-good, heartwarming’ story of a novice teacher who gradually gets used to teaching her fourth grade students in the farm village of Sosa and builds up her confidence. The story sounds ordinary for the first few paragraphs, until she starts to talk about the ‘will to fight’, defeating the U.S. and Britain, dedicating everything to the Emperor, and other Imperialist propaganda points. Today, Sosa is part of Bucheon, a city located 25 kilometers away from Seoul.

(Translation)

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) October 11, 1943

“The story about the acorns” is filled with a will to fight

Teachers’ appreciation for the lovely children

Farm village schools are fighting

Report by a trainee of Seoul Women’s Teachers College (2)

It was now dawn at the farm village school. Today was the day the trainees would finally begin their full-scale training. We had spent a night in an unfamiliar room. Although there was a little bit of discomfort, life with my 51 classmates was pleasant. When I opened the window, a gentle breeze came in over the golden ears of rice soaked in the night mist. In the fresh air, we ate breakfast made with freshly picked daikon radish and bok choy cabbage.

The trainees waited, their hearts racing with new hope for the day ahead. “What kinds of facial expressions will the children have when we meet them?” we wondered.

Soon, it was 8:30 in the morning. It was time for the trainees to go teach for the first time at Sosa North Public National School. They only had to walk from the waiting room to the staff room, but everyone was tense. “Good morning, teachers,” said a large sixth-grade boy, raising his hands in a bow. After responding back saying “Good morning,” I felt somewhat relieved.

At 8:45 a.m., we had our staff morning assembly, a recital of a prayer to the gods, and other announcements. Then the children’s morning assembly began. As the sound of four children blowing their horns reverberated in the air as an admonition, the children, who had been running around the school yard, gathered around the assembly area in front of the school and tried their best to line up quickly, which was a very encouraging sight.

During the morning assembly, we introduced ourselves. When my name was called out as the teacher for the second class of the fourth grade, I involuntarily responded in a loud voice, “Present!” When I stood in front of the children, I got worried, since many things could happen. I looked at the fingertips of the child in front of me and involuntarily stood immobile. The cute little children with bowl haircuts were all lined up in a row. The thought of living with these children for the next sixteen days made me want to talk to them.

I walked up the polished and shining stairs and entered the classroom of the second class of the fourth grade. When I saw the children properly sitting in their chairs waiting for me, I was reminded of my own elementary school days. I was then filled with emotion, realizing that I was now in a position to teach them.

Not long after I calmed down, it was time for me to give a lesson to the students. The students were children from rural villages. I had no idea what kind of knowledge they would have. I was teaching a class on spoken Japanese. Since it was an hour of instruction with children whom I had just met, my heart was aflutter. But I could not let them think that my podium was too high. The children stared at me more and more, as if they did not know of my inner turmoil. However, now that I was at the podium, I was the teacher. I had to be firm. I stared into the dark, shining eyes of each of the nearly 80 children who were seated in rows. My self-awareness of the fact that I was a “teacher of Japan at war” firmly supported me in my heart.

As to how they speak, listening to the five or six students that I had picked, I realized that their topics of conversation were different from those of the urban children. They spoke of “acorns,” “pulling grains out of barley ears,” and other topics that smelled of earth and sunlight. While children in the city read picture books, children here go out to work in the fields and mountains. This kind of life on the ground comes alive in the classroom.

Their way of speaking was rough, but I thought it was precious that the children of the soil had such a healthy spirit and were proud to share their experiences in front of everyone. When I said, “Sosa is a beautiful place,” they all smiled and said, “Yes, it is”. I couldn’t help but think how sweet it was to see a child from a pure farm village so happy to be praised for his or her hometown.

Another thing that surprised me was the fact that the topic of “acorns” and “stories about pulling grains from barley” often included the fact that Japan is now fighting hard to defeat the U.S. and Britain. The stories of the children are not merely “natural life experiences” in the midst of nature in the farming villages. Indeed, the “will to fight” and to destroy the U.S. and Britain permeates and boils over in every acorn and in every ear of barley in everyday life. I was infinitely happy to see this “will to fight” in the lives of the children of today’s farm villages, and as a national teacher, I was grateful and honored to see it.

In the peaceful and tranquil nature of the farming villages, people live with the sun, the sky, the crops, the cows, and the horses. Life in a farming village where people enjoy nature is now a dream of the past. The true meaning of the Imperial Way of Labor lies in the fact that every stalk of grass and every tree is connected to the nation, and that every hoe and every kiln, the crops and labor in the farming villages are all solely dedicated to the sovereign Emperor alone. It is only natural that the will to fight is now clearly evident in the minds of the children of the farming villages of today, and in the topics that they talk about.

I shouted out in my heart, “Oh, children of the fighting farming villages of Japan! I cannot help but admire your fierce and burning will to fight that is reflected in your pure faces.”

It was recess. My love for the children was boundless, so I couldn’t help but join hands with them in the schoolyard. The autumn sun’s rays were pouring down like a bright rain all over the schoolyard. Oh, the joy of playing hand in hand with those children who were burning with the will to fight! I couldn’t help but think to myself, how could I not feel the joy of an educator here?

In the afternoon, I returned to the waiting room for an afternoon event. Lunch was a delicious dish of kinpira gobo. From 1:00 p.m., Mr. Watanabe gave an instructional lecture on practical training.

- 1. Train individual students with the goal of instilling sincerity.

- 2. Train individual students with the purpose of increasing promptness.

- 3. Train jointly with the students to work organically together.

- 4. Train students as group to work as an organized team.

- 5. Conduct specialized training for emergency situations.

After listening to the above, I went to the practical training site and watched the fourth graders work on point #1.

(By Ayako Hoshimura)

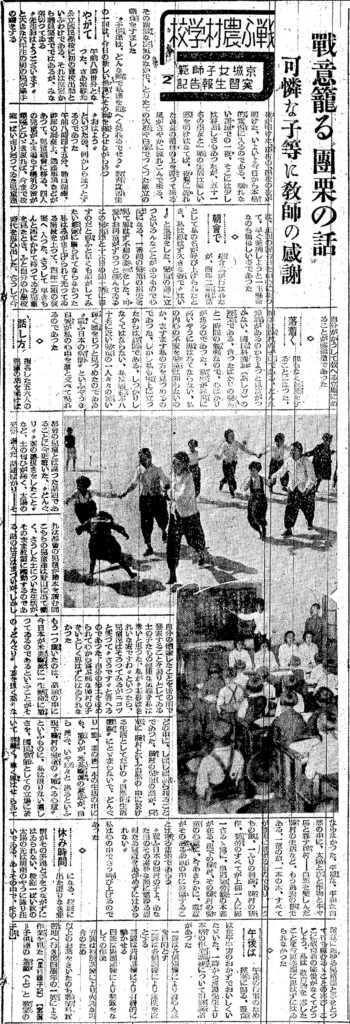

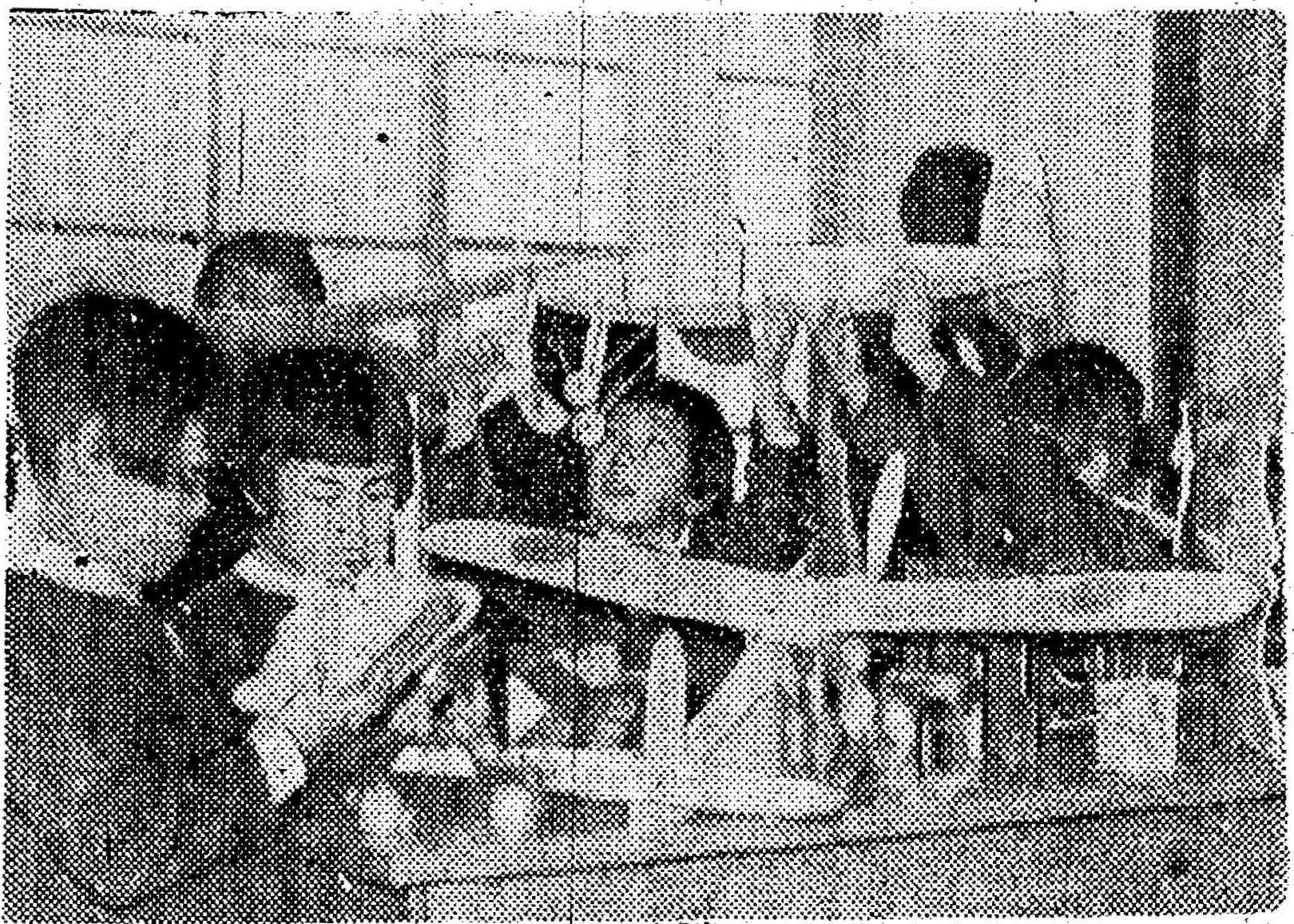

Photos: Children’s play (above) and children in the classroom (below)

Source: https://www.archive.org/details/kjnp-1943-10-11

(Transcription)

京城日報 1943年10月11日

戦意籠る”団栗の話”

可憐な子等に教師の感謝

戦う農村学校

京城女子師範実習生報告記(2)

夜が明けた。農村の学校の夜が明けた。いよいよ今日から本格的実習に入るのである。馴れない部屋での一夜。そこには少しは気苦しさもあったが、五十一名の学友と一緒の生活は愉しい。窓を明けはなてば、夜霧に濡れた黄金の稲穂の上を渡って来る風がさやかに流れこんでくる。その新鮮な空気のなかで、とりたての大根や白菜でつくった献立の朝食をすました。

”子供達は、どんな顔で私達を迎えて呉れるのでしょう”教育実習生の一同は、今日の新しい希望にその胸を躍らせながら待つ。

やがて、午前八時三十分となった。さあ素砂北公立国民学校に初の登校出勤というわけである。それは控室から職員室までではあるが、みな張切っている。”先生おはようございます”と大きな六年生の男の児が挙手の礼をする。”おはよう”といった後、何かしらほっとするのであった。

午前八時四十五分、職員朝礼、神拝の詞奏上、通達事項などがあって、児童朝会に移る。四人の児童がふき鳴らす喇叭の音が諌暁とひびき渡れば、今まで校庭一ぱい走り廻っていた児童達は、正面の号令台を中心に集って、早く整列しようと一生懸命なのも頼母しい姿であった。

朝会で紹介式が行われたが、四年二組配当として私の名が呼び上げられたとき、私は思わず大きな声で”はい!”と返事をした。児童の前に立つといろんなことがあるもので心配になる。一番前の児童の指先を見て思わず不動の姿勢をした。可愛いお河童がずらっと並んでいる。その児童達と十六日の間一緒に暮すのだと思うと早くも話がしてみたい欲望に駆られてならなかった。

私がみがき上げられて光っている階段を上って、四年二組の教室へ入った。そうして早きちんと席にかけて待っている児童を見たとき、ふと自分の小学校時代を思い出した。そうして今自分がこうして教える立場にあることが感無量であった。

落ち着く間もなく授業をすることになった。相手は農村の子供である。どんな知識があるのか、ちょっと見当がつかない。国民科国語(話し方)の授業である。会ったばかりの児童と一時間の勉強なので、心ばかりが焦るのであった。教壇が非常に高いように思われてならない。私の内心の不安を児童は知らないのか、ますます私の方を見つめるのであった。しかし私も壇上に立ったからは教師である。しっかりしなくてはならない。私は居並ぶ八十名に近い児童の一人一人の黒い輝く瞳をじっと見つめたのである。”戦う日本の教師”というような自覚が私の心中を凛と支えて呉れるのであった。

話し方:指名した五六人の児童の話を聞けば、都会の児童とは違った話題であることに今更訊いた。”どんぐり””麥の穂抜きをしたこと”など、土の匂いが高く、太陽の光が滲んだ話題ばかり。それは都会の児童が絵本を読む間、こちらの児童達は野山に出て働く。そうした土についた生活がそのまま教室に躍動するのである。

話の仕方はまずいが、しかし自分の体験したことを皆の前で発表することを誇りとしている土の子たちの健康な気魄を私は尊いと思った。私が”素砂はきれいな處ですね”といったら、児童達はそろってみるがニッコリと笑って”そうです”と答えるのであった。自分の郷土をほめられて心から喜ぶ純な農村の子をいとしく思わずにはいられなかった。

もう一つ驚いたのは、話題の中に今日本が米英撃滅に一生懸命に戦っているのであるということがその”どんぐり””麥を抜く話”などの中に、しばしば語られることであった。農村の児童の話が、只単に農村という自然の中に於ける生活としてだけの”自然的生活体験”にとどまらないで、どんぐり一個、麥の穂一本の生活の中にも、戦いが、米英撃滅の意志が、自ら滲み、いや烈々と沸るという現下農村の児童の”戦える心意”というものに、私は限りない嬉しさを、国民教師としての立場に於いて有難く、尊く思わせられてならなかった。

平穏な、平和な自然の中に、太陽と空と作物と牛や馬と暮す農村。自然を楽しんだ農村の生活など、もう過去の夢である。一茎の草、一本の木、すべてが国家に通ずるものであり、一うちの鍬、一ふりの利窯、農村の耕作、勤労のすべてが上御一人に帰一さるる處に、皇道勤労観の本義が在る。現下の農村、その農村の児童の心意に、今あきらかに、戦意がその語る話題の中に発露することは寧ろ当然であろう。

”戦う日本の農村の子よ。あなた達のその素朴な顔に燃ゆる烈烈たる戦意をあがめずにはいられない”私は心の中でそう叫び上げるのであった。

休み時間になる。校庭に出た限りなき愛情がその子達と手をつながずにはいられない。校庭一ぱい秋の太陽の光りは明雨のように降り注いでいる。ああその中で、その戦意に燃ゆる児童達と手をとって打ち戯むるることの喜び。ここに教育者の愉悦がなくてどうしよう。私は教育者に思わずにはいられなかった。

午後は午後の行事のため控室に帰る。昼食は金平牛蒡のおかずでおいしくいただいた。一時から渡辺先生より本格の作業訓練について補導講話があった。

- 一号は各個訓練により真心入念を目的とす。

- 二号は各個訓練により速度を旨とする。

- 三号は共同訓練により有機的に働かせる。

- 四号は集団訓練により整隊をなしての作業。

- 五号は特別訓練により火急な場合のため。

以上のお話をきいたのち、職業科実習地へ行き、第四学年の一号による作業を見た。

(星村綾子記)

【写真=子供達の遊戯(上)と教室の子供】