Japanese news staff wrote sad and internally conflicted farewell essays to the Korean people in the very last page of Keijo Nippo (colonial propaganda newspaper) published under Japanese control before takeover by Korean activists on Nov. 2, 1945

2024-01-17

463

1864

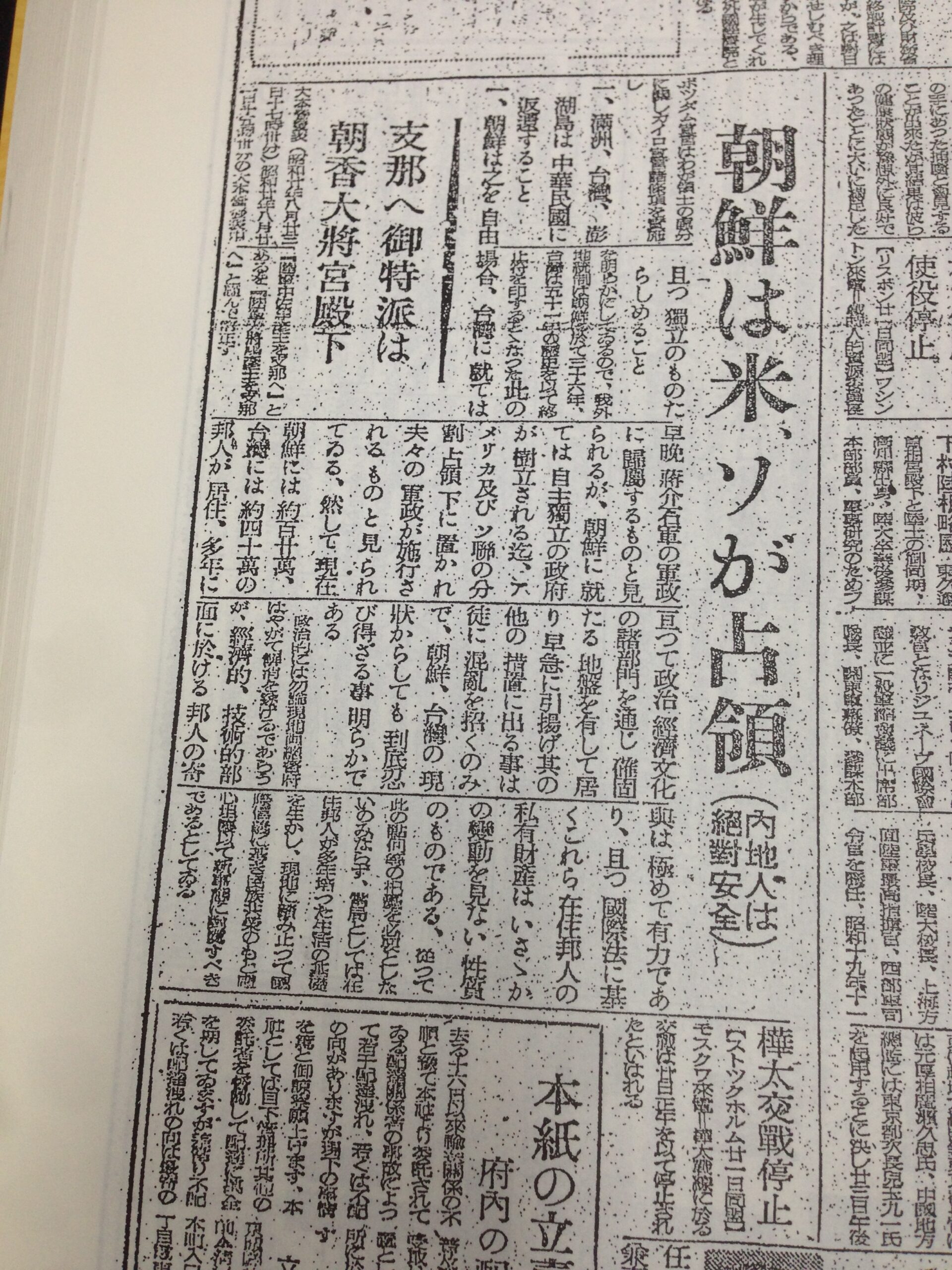

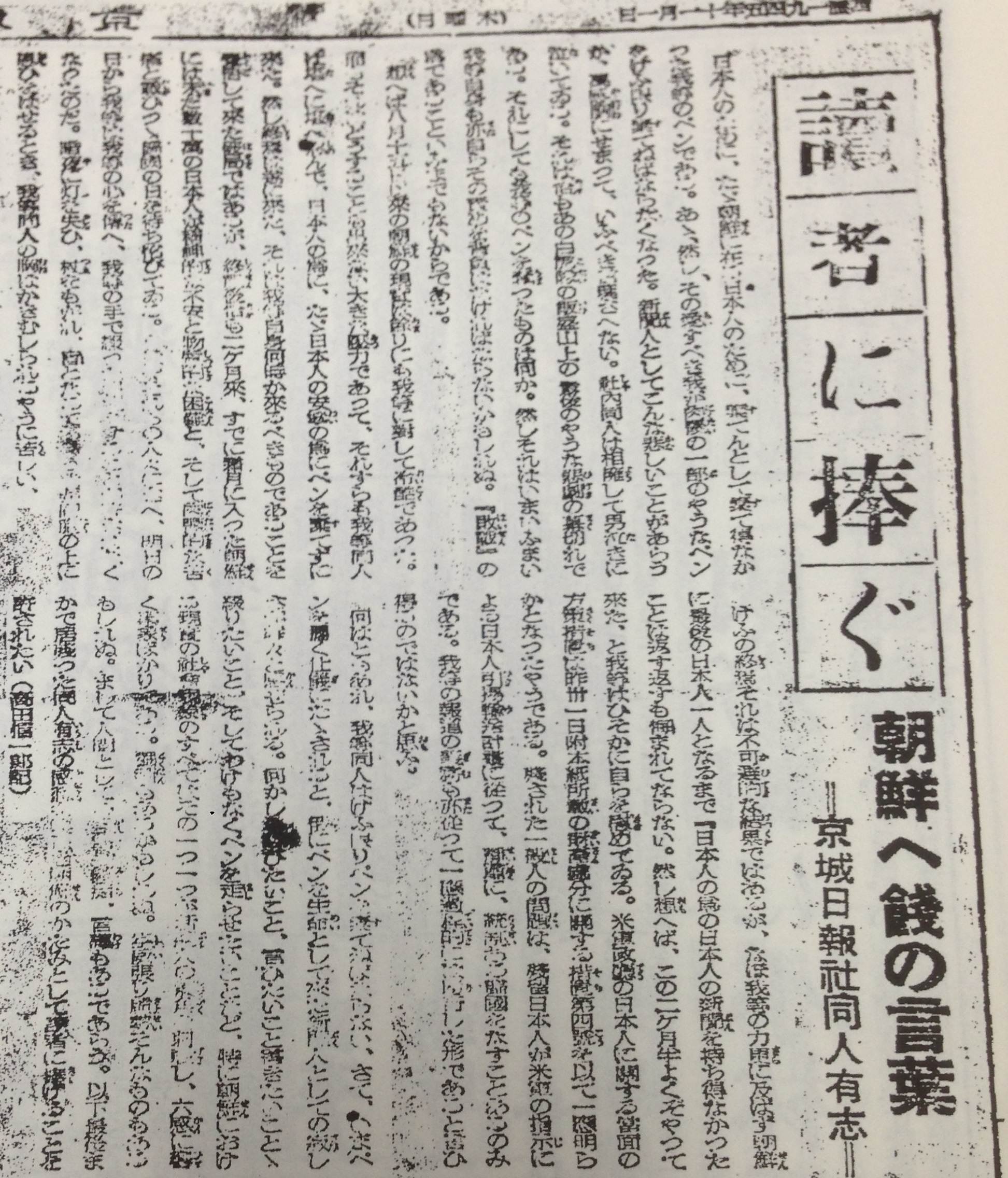

The following is content from a Seoul newspaper published on November 1, 1945, two and a half months after Japan’s surrender in World War II and the liberation of Korea. Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo), the colonial era newspaper that had served as the main propaganda newspaper for the whole of colonial Korea from 1909 to 1945, was still publishing in Japanese as the national newspaper of Korea. The ethnic Japanese staff managed against all odds to retain control over the newspaper during those two and a half months, until they were finally forced to relinquish control to the Korean employees. These Koreans independence activists took over and subsequently continued the publication of this newspaper in Japanese with an avowed Korean nationalist editorial stance from November 2nd until December 11th, 1945.

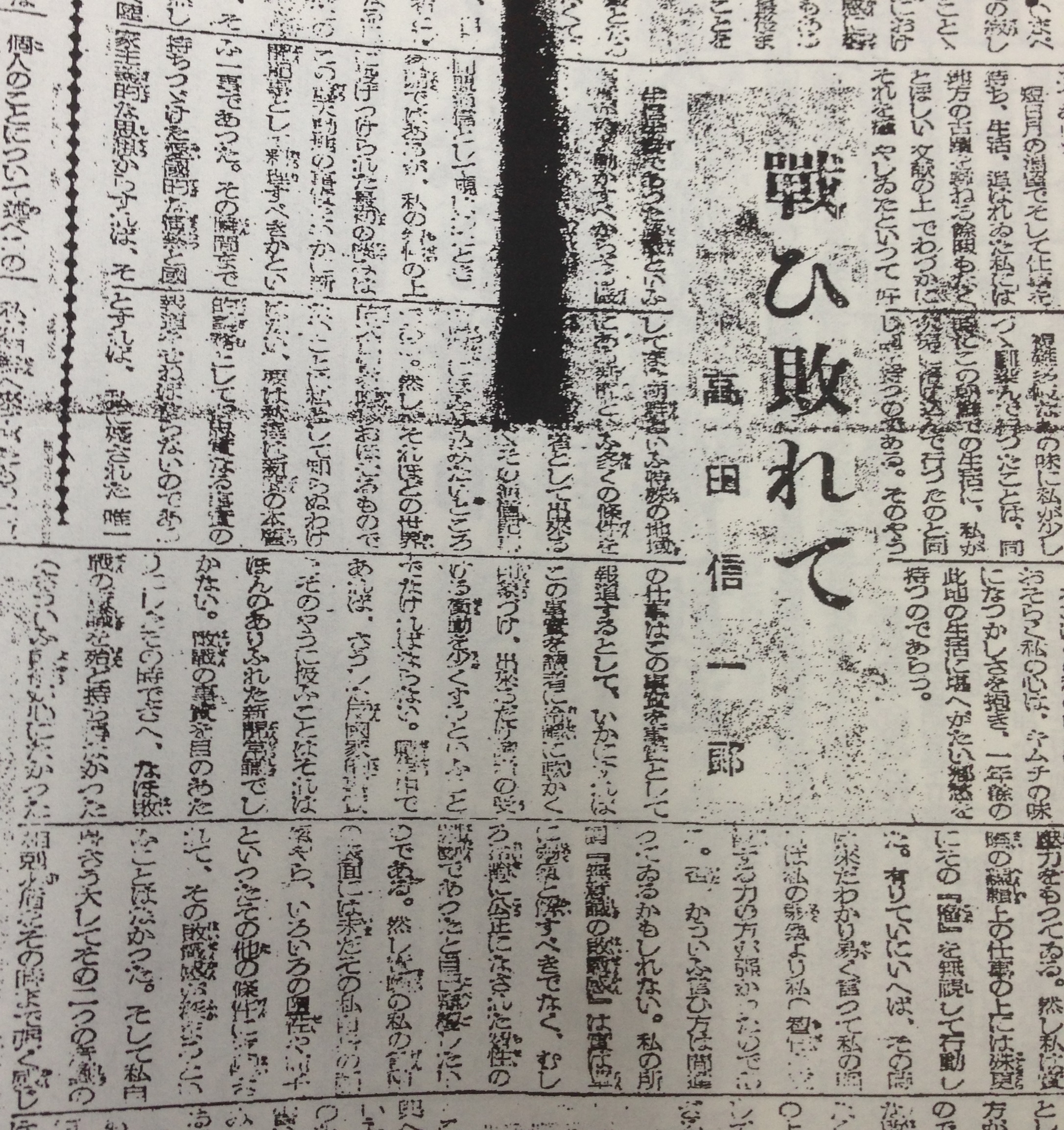

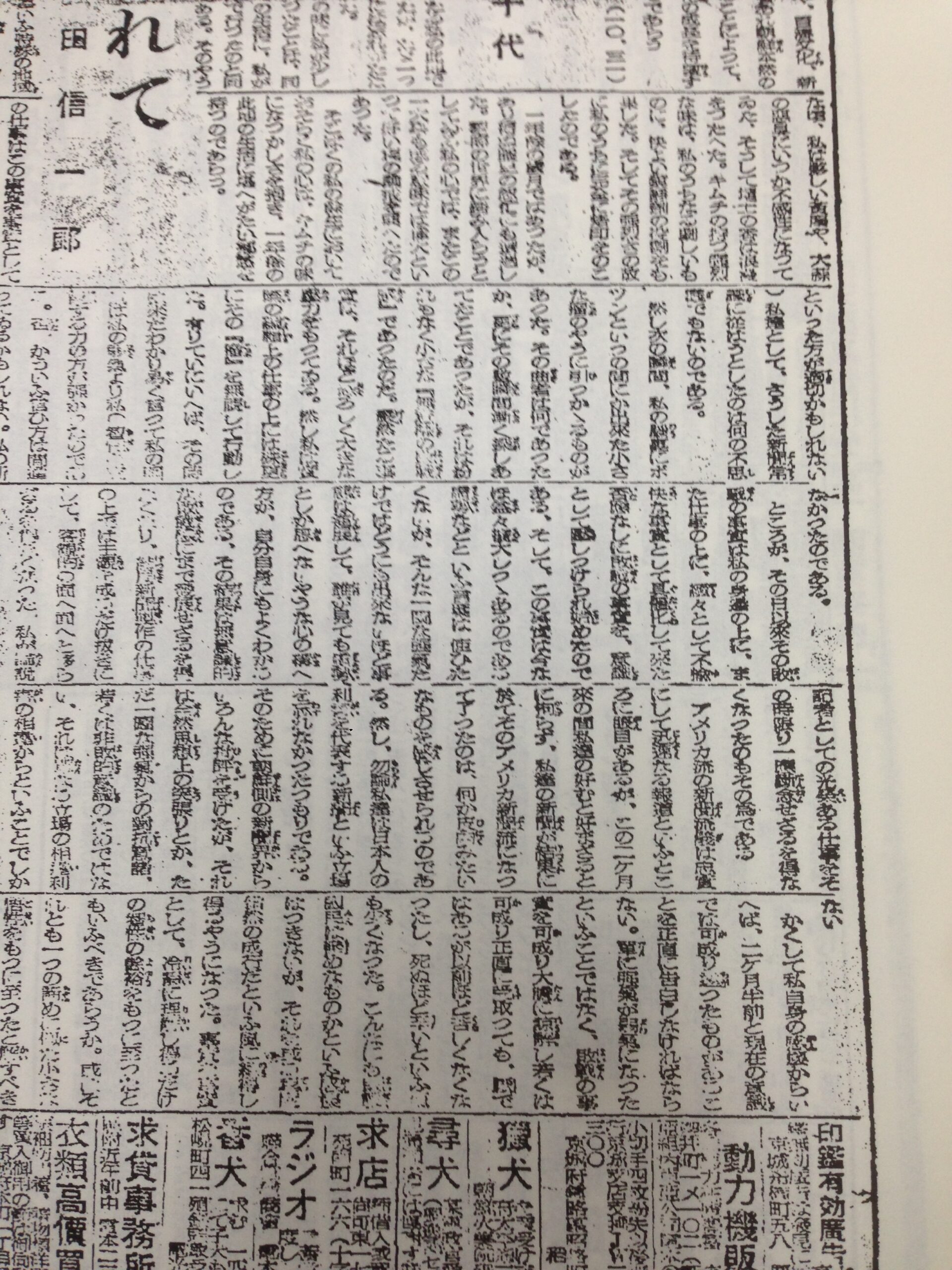

However, before the ethnic Japanese staff was forced to leave, they were allowed to publish one last issue, dated November 1st, 1945, with the very last page dedicated to farewell messages that they wrote to the Korean people as a memento, in which they eloquently express their sad and conflicted thoughts and feelings. Unfortunately, I found this last page in poor condition with big ink blots, gashes, and faded text, so it was very difficult to read them. Nonetheless, due to the compelling content of these long forgotten messages, I decided it was worth spending some time deciphering them as much as I could. There were seven different essays on this page with six different authors. Due to their sheer length, I will share two of the essays in this post, and share the rest in later posts as I unlock this long forgotten time capsule.

From what I can gather from reading these essays, these Japanese news editors were no longer writing as regime spokesmen, but rather as private individuals and as proud news professionals. They felt besieged in their stubborn determination to keep the national newspaper of Korea as a newspaper representing ethnic Japanese interests, for the sake of the Japanese people still remaining in Korea. Understandably, this created conflict with the Korean news community and ultimately led to the November 2nd Korean takeover.

Their essays reveal a profound sense of sadness and internal conflict as the authors grapple with the reality of defeat. Yet, remarkably, there is an absence of bitterness or resentment towards the Korean people or others. The tone of the essays is, in fact, quite gracious. One essay notably extends well-wishes to the Korean people in their endeavors to build their new nation. The essays also include interesting personal anecdotes, some of them about their own families.

This post is a continuation of my ongoing exploration of the old newspaper archives from 1945 Korea that I checked out at the National Library of Korea in September 2023.

[Translation]

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) November 1, 1945

To Our Readers

Words of Farewell to Korea

From the Staff at Keijo Nippo Newspaper

We have found it difficult to put away our pens, which we had dedicated solely for the Japanese people who are in Korea. Ah, but as of today, the time has now come for us to part with this beloved part of our bodies, our pens. Is there anything more sorrowful for a journalist? Overwhelmed with countless emotions, we find ourselves at a loss for words. The members of our editorial team are embracing each other, crying tears of men. The scene resembles the tragic end of the Byakkotai Samurai warriors on the top of Iimori Hill. But what has robbed us of our pens? Now is not the time to speak of it. Perhaps we too must bear some responsibility. It goes without saying that this is due to our “defeat in war”.

Since August 15th, the reality in Korea has been excessively harsh for us. It was an immense pressure that we could do nothing about. Yet, we endured, never abandoning our pens for the sake of the Japanese people, for the sake of their peace and tranquility. However, the end has finally arrived. It was a catastrophe we had braced ourselves for, but two months after the end of the war, in a Korea now entering the month of November, hundreds of thousands of Japanese are still awaiting their return to Japan, battling mental unrest, material hardship, and physical suffering.

From tomorrow onward, we can no longer convey our thoughts or write with our own hands to those people… Losing our light in the dark night, our canes broken, our thoughts turn to the sky… and our hearts are torn with pain.

Today’s end is an inevitable outcome, but we regret not being able to maintain “a newspaper for the Japanese by the Japanese” in Korea until the very last Japanese person remains. However, we console ourselves thinking that we have done well over these last two and a half months. The immediate policies of the U.S. Military Government regarding the Japanese were somewhat clarified by the Property Disposition Measure No. 4, published in our paper on the 31st of last month. The issue for the remaining civilians is to return to Japan in a calm and orderly manner, following the U.S. military’s plan for repatriating Japanese citizens. We believe we have somewhat fulfilled our duty to report the news during this process.

Regardless, today we must lay down our pens. And now, being forced to put down our pens, as journalists for whom the pen is our lifeblood, we suddenly feel a profound desolation. There are so many things we want to ask, say, explain, write, and simply scribble without reason. Each and every social phenomenon in Korea stimulates the senses of a journalist, resonating with all six senses. There may be presumptions. There may be bravado and posturing. As human beings, we may even make excuses. Finally, we would like to offer the following sentiments of the remaining staff as a memento to our readers in Korea. (Written by Shinichirō Takada)

Defeated in War

By Shinichirō Takada

The fact of the war’s end, which I had half-believed and half-doubted, became an immovable and solemn reality… When I glimpsed it through Dōmei News Agency reports, the first dilemma thrown upon my intellect, albeit feeble, was how to cook up a newspaper article based on this earth-shattering fact. Until this moment, driven by patriotic passion and nationalist ideology, and considering various conditions, including the fact that this newspaper is in a unique place called Korea…

The essence was, if we were to faithfully report the truth in accordance with our essential duty as a newspaper, the only task that was left for us was to report this fact as a fact, and somehow imprint it calmly and in detail on the readers, while minimizing the shock that they received as much as possible. During the war, handling such anti-nationalistic facts in this manner was just the common sense of the newspaper. Even when faced with the fact of defeat, we hardly understood the common sense of defeat at that time (or perhaps it is more appropriate to say that we did not have that luxury in our minds). It was not surprising for us to follow such newspaper common sense.

But the next moment, something nagging like a small lump suddenly formed in my mind. What was this culprit? It took a few moments to find it, but it was undoubtedly a small “unconscious sense of defeat.” This stark reality had such a terrifying and immense pressure. However, in my actual editorial work, I particularly ignored this “lump.” To put it plainly and simply, at that time, my optimism dominated my intellect more than my pessimism did. No, actually, that might be the wrong way to say it. My so-called “unconscious sense of defeat” should not be interpreted as mere pessimism, but rather, I want to defend myself by saying it was a calm and fair judgment of intellect. But in reality, the surface of my current self was still dominated by my own optimism as well as other conditions, such as various inertias and face-saving tendencies, and this sense of defeat did not deepen. And until then, I did not feel such a strong contradiction between these two consciousnesses.

However, since that day, the fact of defeat began to materialize as an unpleasant reality in my personal life and work. I began to be involuntarily pressed by the fact of defeat as a consciousness. And this fact is still expanding even now. I do not want to use the word bluff, but the situation has progressed to the point where such stubborn optimism alone cannot handle it, and it’s clear to me that my mental preparation seems nothing but a bluff. As a result, I had no choice but to develop an unconscious sense of defeat and ultimately had to shift from subjectivity to objectivity in my work on newspaper production. As an editorial writer, I had no choice but to temporarily give up my honorable job at that time.

American-style journalism focuses on faithful and rapid reporting, but over these two months, regardless of our preference, our newspaper has ironically become akin to that American style of journalism. Of course, we have not forgotten our position as a newspaper representing the interests of the Japanese people. We have received various criticisms from the Korean newspaper community for this, but it is not due to any ideological confrontation or sheer obstinacy or anti-defeatist consciousness. Rather, it is merely a difference in positions and interests.

Thus, I must honestly confess that there is a considerable difference between my consciousness two and a half months ago and now. It is not just that optimism has turned to pessimism, but I have come to boldly understand or honestly accept the fact of defeat. It is agonizing, but not as painful as before, and the feeling of dying from the pain has decreased. The feeling that the defeated Japanese nationals are so miserable is endless, but I have come to accept it to a certain extent as a natural course of events. It could be said that I have attained the intellect and composure to calmly understand the facts as they are. Or perhaps I have come to possess a small enlightenment, akin to consolation. Anyway, I am in such a state of mind now, whether it is progress or regression.

This consciousness of defeat will not end as it is. That is, the consciousness of defeat will inevitably affect my ideological tendencies to a greater or lesser extent. This is a serious matter. To be honest, I have already started to have doubts and concerns in this regard. Sooner or later, a true ideological turning point due to the end of the war will come to me. I grew up in the era of liberalism, learned in the winds of socialist thought, and was dyed in nationalist thought upon entering real society, further intensified by the long war. Now facing a significant ideological transition, my feelings are immensely complex. If I can isolate myself from everything after returning home to Japan and gain the confidence to overcome this period of ideological transition, I think there is no greater happiness.

[Transcription]

京城日報 1945年11月1日

読者に捧ぐ

朝鮮へ餞の言葉

=京城日報社同人有志=

日本人のために、ただ朝鮮に在る日本人のために、棄てんとして棄て得なかった我等のペンである。ああ、然し、その愛すべき肉体の一部のようなペンをきょう限り棄てねばならなくなった。新聞人としてこんな悲しいことがあろうか。万感胸にせまって、いうべき言葉さえない。社内同人は相擁して男泣きに泣いている。それは恰もあの白虎隊の飯盛山上の最後のような悲劇の幕切れである。それにしても我等のペンを奪ったものは何か。然しそれはいまいうまい。我等自身も亦自らその責めを背負わなければならないかもしれぬ。『敗戦』の為であるこというまでもないからである。

想えば八月十五日以来の朝鮮の現実は余りにも我等に対して冷酷であった。前もそれはどうすることも出来ない大きな圧力であって、それすらも我等同人は堪えに堪え忍んで、日本人の為に、ただ日本人の安寧の為にペンを棄てずに来た。然し終焉は遂に来た。それは我等自身何時か来るべきものであることを覚悟して来た破局であるが、終戦後恰も二ヶ月来、すでに霜月に入った朝鮮には未だ数十万の日本人が精神的な不安と物質的な困難と、そして肉体的な苦痛と戦いつつ帰国の日を待ち侘びている。

我等はそれらの人々にさえ、明日の日から我等は我等の心を伝え、我等の手で綴った[illegible]できなくなったのだ。暗夜に灯を失い、杖をも折れ、[illegible]の上に思いをはせるとき、我等同人の胸はかきむしられるように苦しい。

きょうの終焉それは不可避的な結果ではあるが、なお我等の力更に及ばず朝鮮に最後の日本人一人となるまで『日本人の為の日本人の新聞』を持ち得なかったことは返す返すも悔まれてはならない。然し思えば、この二ヶ月半よくぞやって来た、と我等はひそかに自らを慰めている。米軍政庁の日本人に関する当面の方策措置は昨三十一日附本紙所載の財産処分に関する措置第四号を以て一応明らかとなったようである。残された一般人の問題は、残留日本人が米軍の指示による日本人引揚輸送計画に従って、静粛に、統制ある帰国をなすことあるのみである。我等の報道の義務も亦従って一応過程的には履行した形であると言い得るのではないかと思う。

何はともあれ、我等同人はきょう限りペンを棄てねばならない。さて、いまペンを置く仕儀にたたされると、俄かにペンを生命として来た新聞人としての寂しさを犇々と感ぜられる。何かしら問いたいこと、言いたいこと、説きたいことと綴りたいこと、そしてわけもなくペンを走らせたいことなど、特に朝鮮における現実の社会現象のすべてはその一つ一つが新聞人の感覚を刺激し、六感に響く現象ばかりである。独断もあるかもしれぬ。空威張り、虚勢そんなものもあるかもしれぬ。まして人間として[illegible]言い訳もあるであろう。以下最後まで居残った有志の感慨の記録を朝鮮のかたみとして読者に捧げることを許されたい。(高田信一郎記)

戦い敗れて (高田信一郎)

半信半疑であった終戦という事実が心を動かすべからざる厳粛[illegible]同盟通信として覗いてたとき、貧弱ではあるが、私の知性の上に投げつけられた最初の悩みはこの驚天動地の事実をいかに新聞記事として料理すべきかという一事であった。この瞬間まで待ちつづけた愛国的な情熱と国家主義的な思想からすれば、そしてまた朝鮮という特殊の地域にある新聞という多くの条件を[illegible]

要は私達は新聞の本質的義務として忠実なる事実の報道をせねばならないのであるとすれば、私に残された唯一の仕事はこの事実を事実として報道するとして、いかにすればこの事実を読者に冷静に細かく印象づけ、出来るだけ読者の受ける衝動を少なくするということでなければならない。戦争中であれば、そうした反国家的事実をそのように扱うことは、それはほんのありふれた新聞常識でしかない。敗戦の事実を目のあたりにしたその時でさえ、なお敗戦の常識を殆ど持ち得なかった。(そういう余裕が心になかったといった方が適切かもしれない)私達として、そうした新聞常識に従おうとしたのは何の不思議でもないのである。

然し次の瞬間、私の脳裏にポツンといつの間にか出来た小さな瘤のように引っかかるものがあった。その曲者は何であったか。更にその数瞬間漸く探しあてたことであったが、それは紛れもなく小さな『無意識の敗戦感』であったのだ。厳然たる事実は、それほど恐ろしく大きな圧力をもっている。然し私は実際の編集上の仕事の上には殊更にその『瘤』を無視して行動した。有りていにいえば、その時は未だわかり易く言って、私の強気は私の弱気より私の知性を支配する力の方が強かったのである。否、こういう言い方は間違っているかもしれない。私の所謂『無意識の敗戦感』は実は単に弱気と解すべきでなく、むしろ冷静に公正になされた知性の判断であったと自己弁護したいのである。然し実際の私の現在の表面には未だその私自身の強気やら、いろいろの惰性や面子といったその他の条件に支配されて、その敗戦感が深まるということはなかった。そして私自身そう大してその二つの意識の相剋矛盾をその時まで強く感じなかったのである。

ところが、その日以来その敗戦の事実は私の身辺の上に、また仕事の上に、続々として不愉快な事実として具体化して来た。否応なしに敗戦の事実を、意識として圧しつけられ始めたのである。そして、その事実は今なお益々拡大しつつあるのである。虚勢などという言葉は使いたくないが、そんな一途な強気だけではどうにも出来ないほど事態は進展して、誰が見ても虚勢としか思えないような心の構え方が、自分自身にもよくわかるのである。その結果は無意識的な敗戦感にまで発展せざるを得なくなり、結局新聞製作の仕事の上では主観を成るだけ抜きにして、客観的の面へ面へと移らざるを得なくなった。私は論説の記者としての光栄ある仕事をその時限り一応断念せざるを得なくなったのもその為である。

アメリカ流の新聞流儀は忠実にして迅速なる報道というところに眼目があるが、この二ヶ月来の間、私達の好むと好まざるとに拘わらず、私達の新聞が結果に於いてそのアメリカ新聞流になってしまったのは、何か皮肉みたいなものを感じさせられるのである。然し、勿論私達は日本人の利害を代表する新聞という立場を忘れなかったつもりである。そのために朝鮮側の新聞界からいろんな批評を受けたが、それは全然思想上の突張りとか、ただ一途な強気からの対抗意識、若しくは非敗的意識のためではない。それは単なる立場の相違利害の相違からということでしかない。

かくして私自身の感慨からいえば、二ヶ月半前と現在の意識では可成り違ったものがあることを正直に告白しなければならない。単に強気が弱気になったということではなく、敗戦の事実を可成り大胆に諒解し若しくは可成り正直に受け取っても、悶ではあるが以前ほど苦しくなくなったし、死ぬほど辛いという気も少なくなった。こんなにも敗戦国民は惨めなものかという感情はつきないが、それを或る程度当然の成り行きだという風に納得し得るようになった。事実を事実として、冷静に理解し得るだけの知性と余裕をもつに至ったともいうべきであろうか。或はそれとも一つの慰めに似た小さな悟性をもつに至ったと解すべきであろうか。とにかく、一つの進歩か退歩かしらぬが、いま私はそんな心境である。

ただこの敗戦の意識はそのままで終るわけはない。即ち敗戦の意識は私の思想上の動向にも大なり小なり影響を与えずにはおかないであろう。これは大変なことである。すでに私は正直に言って、一つの迷い、一つの悩みをそういう点に持ち始めている。晩かれ、早かれ、そうした終戦による本当の思想の転機が私にも訪れることと思うが、自由主義時代に育ち、社会主義的思想の風の中に学んで来た私として実社会に入って国家主義的思想に染色され、長い間の戦争によって更に色揚げされた格好の私である。いま又大きな思想的転換期に直面して、私の感慨は千万無量である。帰国せる後の私の第一の余裕が一切のものから隔離され得て、この思想転換期を乗り切るだけの自信を得るために与えられれば、私はこんな幸福はないと思っている。