Young Korean men were ‘beaten into shape’ at militaristic farmers’ dōjō (Imperial Japanese training indoctrination camp) to cultivate the next generation of rural Korean leaders who would spread the Imperial Way of farming throughout the Korean countryside (Daejeon, 1943)

This is my translation and transcription of a news article from Keijo Nippo, a propaganda newspaper and mouthpiece of the government of Japan-colonized Korea. It has never been republished or translated before, to the best of my knowledge.

I have to acknowledge historian Jeong Jae-jeong (정재정/鄭在貞) for writing an excellent paper about Imperial Japanese indoctrination camps in Korea, including farmers’ dōjōs, in his 2005 paper, ‘日帝下朝鮮における国家総力戦体制と朝鮮人の生活’ (‘The National Total War System in Korea under Imperial Japanese rule and the lives of the Korean people’), which he wrote in Korean and Japanese as part of a project of the Japan-Korea Cultural Foundation (Japanese language PDF link, Korean language PDF link). Unfortunately, this article is not available in English.

As Jeong explains in his papers, colonial authorities set up training camps and centers for students, laborers, farmers, young women, and even government officials to indoctrinate Koreans in Imperial Japanese ways. The Yuseong Farmers’ Dōjō was one training camp that was originally set up more as a normal vocational center for local men to learn the latest modern farming techniques, but later taken over by Imperial Way fanatics to become more like a religious cult indoctrination center. There was apparently also a parallel Yuseong Women’s Training Center for young women to learn farming techniques, child rearing, and house chores, which Jeong mentions in his paper.

This article describes inmates singing songs by Ninomiya Sontoku (alternatively named Ninomiya Ginjiro), whose teachings South Korean dictator Park Chung-hee adopted in his New Community Movement, which was a campaign to modernize rural South Korea incorporating ideas from traditional Korean communalism and didactic techniques that were commonly used in Imperial Japan. Quoting a passage from The New Community Movement: Park Chung Hee and the Making of State Populism in Korea by Han Seung-mi:

Nevertheless, the New Community Movement met with genuine response from the countryside. Its key methodology was spiritual training. It was enforced under guidelines set by Park himself, and “non-economic” mental/social issues were addressed in order for the economy to prosper. Park was influenced by Japanese-style mental training, as were his high-ranking officials and policy advisors, who also believed in a Weberian emphasis on work ethics. “The Swiss had the Puritans, and the Japanese have Ninomiya Ginjiro” (interview, April 1999). Interesting, this comment by a former NCM policy maker at the Blue House was echoed by an elderly farmer in the countryside: “I knew instantly what the president was getting across. It was Ninoyama Ginjiro! He was in our 6th grade textbook!” (Interview with a farmer in his seventies, Yeoju County, Kyunggi Province, May 1999). In fact, it assumed an urban bias to assume that the culture of poverty—laziness, despair, and intemperance—was behind the slow economic growth in the countryside. Farmers in general had not given up on life before the NCM was introduced, as the slogans suggested. Rather, the problem was structural in nature.

(Translation)

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) May 3, 1943 (Monday Special Edition)

Increase Production in Harmony with the Earth

Valiant Training Without Any Sundays Off

Young People Leading Tomorrow’s Farming Communities

In order to win the Greater East Asia War, it is necessary to increase production in all areas of production, and the Korean peninsula is currently continuing its daring battle toward increasing its military strength. In particular, Korea, which is called the ‘granary peninsula,’ is in a position of having to fulfill its duty given to it to increase food production. However, the emphasis on increasing food production is not limited to the conventional increase in crop yields. Indeed, Governor-General Koiso stresses the need to turn the farmers of the Korean peninsula into farmers of the Imperial Way at every opportunity, and explains the necessity of spiritual training. To this end, each province is committed to training the young men who are to become the central figures in the rural villages, and they are constantly training day and night at their respective farmers’ dōjōs.

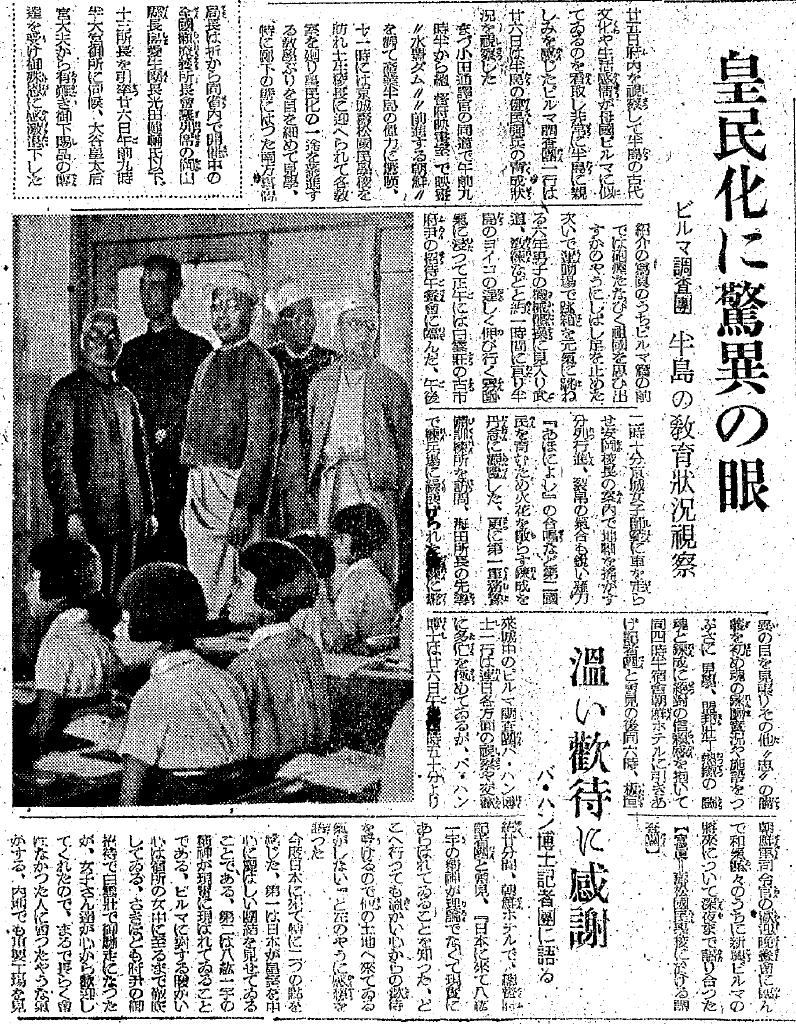

How are the young farmers being trained? How are they creating the core group of young farming men who will carry the future of the Korean peninsula’s farming villages on their shoulders? This newspaper visited the Yuseong Farmers’ dōjō in Chungnam, the oldest farmers’ dōjō in Korea and a model for other provinces, to report with a pen and camera on the reality of “farmers being trained”. [Correspondent Kimura]

|

| The sign says 忠清南道儒城農民道場, or Chungcheongnam-do Yuseong Farmers’ Dōjō. |

How the dōjō is organized

The first farmers’ dōjō was established in Korea not long ago, during the reign of Governor-General Ugaki, as one of the measures to realize the policy of rural development, and was established in each rural village to train a core group of young men to become self-sufficient farmers. The Yuseong Farmers’ dōjō, established in June 1934, was the spearhead of this project. Since then, this facility has been recognized by each province as being very useful for training farmers, especially for creating core groups of young men in each village, and now there are no provinces without a farmers’ dōjō. At first, the goal was to establish self-sufficient farming through self-rehabilitation, but after the war, under the great mission to secure food for the Co-prosperity Sphere under the Greater East Asia War, there will be a strong demand to practice farming the Imperial Way, not simply to expand the area of arable land and rationally use fertilizers. They are being trained to “love the soil, live with the soil, and die with the soil” just as they do in mainland Japan, to practice Korean farming carried forth by spiritual training. For this reason, the Yuseong Farmers’ dōjō, which serves as a model for all of Korea, has increased its capacity from 60 to 100 inmates this year to accelerate the Imperialization of Korean farmers.

|

| Photo: A panoramic view of the Yuseong Farmers’ dōjō in Chungnam. |

This dōjō is located 12 kilometers from Daejeon, or a 30-minute walk from the Yuseong Hot Springs. The dōjō is surrounded by pine forests on one side and farm fields on three sides. It has a blessed environment with a view of orchards run by mainland Japanese operators in the far distance. The dōjō students currently undergoing training here are 60 men selected from the six counties of Daedeok, Yeongi, Gongju, Nonsan, Asan, and Cheonan. They live together in independent farmhouses in groups of five and undergo training without taking time off on Sundays.

The farmhouses were given names such as “rehabilitation,” “promotion,” “self-reliance,” “service,” “community,” “thrift,” “wise farming,” “benevolent farming,” “diligent farming,” “respectful farming,” “encouraging farming,” “loving farming,” and so on. For each farmhouse, whoever had the most outstanding academic background or agricultural ability was chosen to be the house leader, and he was placed in charge of the four remaining housemates. There are 12 farmhouses, six each on the east and west sides of the dōjō, with five people living in the same room, forming a completely independent farmhouse. There is a pigpen, a chicken coop, a compost shed, a cow shed, and so on. While they are cramped, they are equipped with the most ideal facilities for Korean farmers. The 12 farmhouses are of the same standard design and currently accommodate five people each. But since the dōjō is being planned to accommodate another 40 people in the near future, each farmhouse will eventually accommodate seven people each. There are plans to build two additional farmhouses. The dōjō owns arable land including rice paddies (4 chō + 1 se + 6 bu = 4.0 hectares or 9.8 acres), farm fields (5 chō + 4 tan + 6 se = 5.4 hectares or 13.4 acres), muddy fields (9 tan + 8 se + 5 bu = 1.0 hectare or 2.4 acres), forestland (6 chō + 8 tan + 6 bu = 6.7 hectares or 16.7 acres), 12 cows, 60 chickens, 18 sheep, and 12 rabbits, and is self-sufficient in everything except miso and soy sauce. On top of that, since annual revenues are 4,800 yen with vegetables alone, it means that highly intensive farming is being practiced compared to farmers overall. Since the number of inmates is increased by 40 while the amount of cultivated land remains the same, this means that we will have to put extra effort into intensive farming going forward.

In addition to the house leader, all four members of the farmhouse are assigned to the following tasks in an organized manner: rice cultivation, vegetables, animal husbandry, and facility management. In addition to the work assignments for each house, the dōjō as a whole is assigned a public morals officer, a power facility officer, a sales officer, a purchasing officer, and a cooking officer. All the harvested produce is submitted to the sales officer, and proceeds are transferred to the savings accounts of each farmhouse.

Beat them into shape to stop their “reliance on others”

Dōjō Life

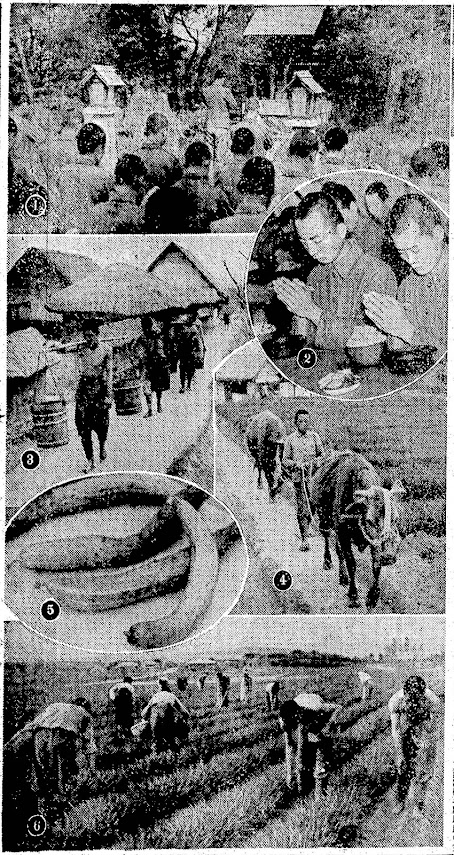

The life of the dōjō students here is the same as that of the Navy: Monday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Friday, and the daily routine is repeated day in and day out with total discipline. In the morning, they wake up at 5:00 a.m., clean up the area around the farmhouse, tidy up the house, and wash up by 5:35 a.m. Then they gather in front of the Ōkura Worship Hall in the pine forest for the morning assembly, during which roll call is held, and then participants reverently bow towards the Worship Hall performing two claps, two bows, and then one clap, followed by Kyūjō Yōhai worship bowing in the direction of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo and then the Ise Jingū Yōhai worship bowing in the direction of Ise Shrine. Then the dōjō leader or instructor gives a speech, followed by national calisthenics exercises. From then until seven o’clock is the first working hour, during which they are assigned to work on such tasks as manure collection, weeding, straw work, farming, and livestock management, and in some cases, they are gathered in the auditorium for lectures.

Breakfast time is from 7:00 to 8:00 a.m. To instill a sense of gratitude for food, they are required to say the pre-meal and post-meal vows three times. For breakfast, the inmate would stand in front of a bowl of miso soup, takuan picked radishes, and a heaping pile of rice, with his palms pressed together, chopsticks between his thumb and forefinger, and say,

“I am deeply grateful to the gods and Buddha for their blessings and the labor of so many people that went into the food being served to us. I will not be averse to eating this food because it tastes bad, nor will I be greedy because it tastes good. Let’s eat.”

After making this vow, he takes his chopsticks, and finishing breakfast, he is full of strength in body and mind, and now he will strive hard to perform the morning’s work. The same vow is made at lunch, but they make the following vow after dinner:

“Now that dinner is over, we are full of strength, so let us reflect on today’s work and prepare for tomorrow.”

In addition, from February until the end of the training period in December, the students are required to memorize six Chinese characters a day, two at a time after each meal, in order to reach the goal of learning 2,000 Chinese characters. Although the dōjō students are usually graduates of national schools (elementary schools), they cannot actually write letters in their everyday language, so this training in Chinese characters is based on their parents’ wishes that, after they return to their villages, they will be able to read the correspondence from the local myeon (township) office and explain the contents to fellow villagers, or at least be able to write letters on their parents’ behalf.

After breakfast and learning Chinese characters, the second work period lasts until 12:50 in the afternoon, and the third work period lasts from 2:00 p.m. to sundown at 7:00 p.m. These are meant to be thorough “training periods” for the dōjō students to become farmers of the Imperial Nation. This daily routine is a time to seek a rethinking of the farming practices which they had been doing at home under the orders of their parents. It is a time to beat them into shape to rethink older farming practices involving reliance on others, which include sowing seasonal seeds according to the calendar, applying fertilizer when they sprout, giving up when it does not rain, and relying on others for help when there is drought. We teach them, if it doesn’t rain, dig a well. If insects appear, take them out. If there is not enough fertilizer, make more compost.

In fact, the farmers in this area only add 100 kan (375 kg) or at most 200 kan (750 kg) of compost per tan (0.1 hectare, or about 1/4 acre), but at this dōjō, they make it an absolute requirement to add 2,000 kan (7500 kg) of compost per tan. At 8:00 p.m., after the hard daytime agricultural training is over and dinner and after-dinner events are finished, lectures, diary entries, and round-table discussions are held as needed. At 9:00 p.m., the night assembly, roll call, night greetings, and greetings to the hometowns are held, and at the sound of the bell at 9:30 p.m., all 12 farmhouses turn off the lights and go to bed at once.

Competence is better than talk

All training is done in the military style, reward good work and punish bad work

Training of dōjō students

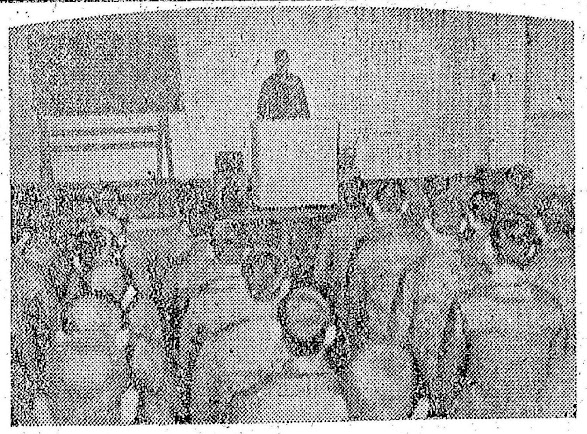

Dōjō students are selected among young men between 17 and 25 years of age. From the time they enter the dōjō in February until the busy farming season in April, they are exclusively trained to become accustomed to group life. This year’s dōjō students have completely picked up military-style training after only two months. One ring of the bell under the worship hall will prompt them to immediately gather at the same time, each farmhouse reporting nothing unusual among the five housemates, and all sixty of them instantly line up.

When the inmates first entered the dōjō, they were all different from each other. The children of poor farmers were accustomed to work, but their behavior was rough, and the worst ones did not even know how to use the toilet. The sons of independent farmers were frail and useless, and the best way to train them all at the same time was to train them military style. Next, it is important for the instructors to blend in with the dōjō students and be with them. Per long-standing practice, head instructors wake up before the students, ring the bell to wake them up, and eat the same meals together with the students. We also strictly enforce the “reward and punishment” policy, profusely praising students for good behavior and readily scolding them for bad behavior, and within two months they somehow become full-fledged dōjō students, just like in the military during the first inspection period.

The dining/lecture hall is crude with desks like chopping blocks, but all around hang the nameplates of students who completed the first through the ninth terms, and in front of them hangs a portrait of Yamazaki Nobuyoshi, a distinguished agricultural expert who is lauded as the ‘father of the Korean farmers’. Written on the portrait are the words, “Ideals are more important than appearances, beliefs are more important than titles, and competence is more important than talk”. The students strive to cultivate their spirit by singing the songs of Ninomiya Sontoku, following the lead of their instructors, so that these words are deeply engraved in the minds of the students.

Open Your Eyes

Characteristics of the dōjō

“Open your eyes! The eyes are not only for seeing what is on the surface. Look at the difference in the growth of the barley here and the barley next to it, and look for what is causing this difference. Opening your eyes means to look and to think.” When managing and sowing the barley, or practicing any work task, they are told to pay attention to the way they look at things. Just because you have sown the seeds and a crop is produced, it does not necessarily mean that you have ‘made’ the crop. Rather, the accomplishment comes when you work hard to take care of the soil, when there is not a single weed in the rice paddy, and the crop has been pleasantly produced. That’s the first time you can say that you have ‘made’ the crop. The dōjō’s approach to crops is aimed at instilling the concept of breathing in harmony with the soil, breaking away from the plundering mentality of agriculture that Korean farmers tend to fall into.

In order to take advantage of the creativity and ingenuity of the dōjō students, the students are allowed to build their own livestock barns, compost sheds, and fences to accompany the 12 farmhouses, designing the structures in accordance with their own ideas. The dōjō is unique in that each farmhouse is led by a house leader, and each cow shed is built according to the students’ own ideas, and each chicken coop is built in a different way.

The production amount for fiscal year 1943 is projected to be 14,434 yen, and the farmers are instructed to reduce the amount land that they have been using to cultivate vegetables from 1 chō + 2 tan (2.9 acres or 1.2 hectares) last year to just 6 tan + 1 bu (1.5 acres or 0.6 hectares) this year, which is half the amount of land used last year, and still generate the same income as last year of 4,800 yen. In order not to reduce the amount of income by cutting back on cultivated land, cultivation cannot be done arbitrarily. Therefore, the farmers are taught accelerated cultivation under the guidance of the staff, and depending on their techniques, they are taught that they can increase their income. In fact, a paper greenhouse has been built on part of the farmland for early cultivation of cucumbers and eggplants, and some of the cucumbers have already been shipped out on April 10th.

Source: https://www.archive.org/details/kjnp-1943-05-03

(Transcription)

京城日報 1943年5月3日 (月曜特輯)

大地と共に増産へ

逞しい日曜なしの錬成

明日の農村を担う若き人々

大東亜戦争を勝ち抜くためには凡ゆる生産部門の増産が要請され、今や半島は挙げて戦力増強に向かって敢闘を続けているが、特に『穀倉半島』と呼称されている我が朝鮮は食糧増産によって与えられた義務を果たさなければならぬ立場に置かれている。而して食糧増産の要諦は従来の作付反別の増加だけに止まらず、小磯総督は機会ある毎に半島農民の皇道農民化を強調し、精神的訓練の必要を説いている。そのためには各道とも農村部落の中心人物たるべき青年層の錬成に心がけ、夫々の農民道場で日夜絶え間なき錬成を行っている。

若き農民は如何に鍛えられつつあるか。明日の半島農村を背負って立つ農村中堅青年はどうして作り出されるか。本紙は農民道場として最古の存在であり、他道の範となっている忠南儒城農民道場を訪れて、ここにペンとカメラによって『鍛えられる農民』の実態を報告する。【木村特派員記】

道場の組織

朝鮮に農民道場が創設されたのは古いことでなく、宇垣総督時代、農村振興政策を具現する一方策として各農村部落に中堅青年の自作農を作るために出来たもので、昭和九年六月設立した儒城農民道場をもって嚆矢とする。その後、この施設が農民錬成のため、特に部落中堅青年を作り出す上に非常に役立つことが各道に認められ、現在農民道場をもたぬ道はない。初めは自力更生による自作農設定を目標としていたが、戦争後は、大東亜戦下の共栄圏内の食糧確保という大使命の下に、単なる耕地面積の拡大、肥料の合理的使用に局限せず、皇国農民道の実践が強く要請され、精神的訓練によって運ばれた半島営農を内地と同様『土を愛し、土と共に生き、土と共に死す』の訓練を行っている。このため全鮮の模範である儒城農民道場では今年から従来の収容人員六十名を百名に増員して、半島農民の皇民化に拍車をかけることになった。

【写真=忠南儒城農民道場の全景】

この道場は大田から十二キロの儒城温泉から更に歩行三十分の地点にあり、一方を松林、三方は道場耕地に囲まれ、遥か彼方には内地人経営の果樹園などが望見出来る恵まれた環境をもっている。現在ここに入所して訓練を受けている道場生は大徳、燕岐、公州、論山、牙山、天安の六郡から選抜された六十名で、これ等が各独立した農舎で五名づつ起居を共にして、日曜日なしの訓練を受けている。

その農舎にはそれぞれ更生、振興、自力、奉仕、共同、勤倹、賢農、篤農、精農、尊農、勧農、愛農等々の舎名がつけられていて、一舎のうち、学歴、農業能力などの優れた者を家長とし、残る四名の舎生の統率をしている。十二農舎は東西に六戸づつ建ててあり、五名の者が同室に起居し、全く独立した農家を形成している。豚舎あり、鶏舎あり、堆肥小屋あり、牛小屋あり...狭い乍らも半島農家の最も理想的な施設が具備されており、十二の農舎は同一規格で、現在は一舎五名づつを収容しているが、近く更に四十名を収容することになっており、そうなると一舎七名となり、ほかに二舎増築の予定になっているが、道場所有耕地は畓四町一畝六歩、田五町四反六畝、垈九反八畝五歩、林野六町八反六歩、家畜は牛十二頭、鶏六十羽、緬羊十八頭、兎十二羽で、味噌、醤油以外のものは一切自給自足し、なおその上蔬菜だけでも年収四千八百円をあげているから他の一般農家に比し高度の集約営農を行っていることになり、人員が四十名殖えても耕地は従前通りであるため今後は一層集約営農という点に力を注ぐことになっている。

農舎には家長のほか四名のもの全部に田畓作係、蔬菜係、飼育係、施設係を決めて秩序ある作業を割り当てている。各舎の割り当ての上に道場全体にも風紀、動力施設、販売、購買、炊事係をそれぞれ決めて、出来た作物は全部販売係に提出し、売上金は農舎毎に貯蓄に繰り入れる。

叩き直す”他力本願”

道場の生活

此処の道場生たちの生活は海軍と同じように月月火水木金金を実行し、総て規律をもって一日の課程を、来る日も来る日も変わらず繰り返している。朝は先ず午前五時起床、五時三十五分までの間に農舎附近の清掃、舎内の整頓、洗面を終って、松林内の大蔵奉祀殿前に集合して朝礼を行う。朝礼は人員点呼ののち奉祀殿に向かって恭しく二拍手、二礼、一拍手の拝礼をし、宮城、伊勢神宮遥拝ののち道場長又は輔導員の訓話があって国民体操をする。それから七時までが第一就業時間で、採肥、除草、藁細工、農耕、家畜管理などをやらせ、場合によっては講堂に集めて講義をすることもある。

七時から八時までが朝食時間であるが、食物に対する感謝の念を植えつけるために三度度々、食前、食後の誓いをさせる。朝食ならば味噌汁と沢庵漬け、山盛りの飯を前にして、合掌の姿勢をとり拇指と人差し指の間に箸をはさんで、

「この食物が食膳に上るまでには幾多の人々の労力と神仏の加護あることを思い、深く感謝致します。この食物を戴くことを過分に思い、不味いからとて厭うことなく、美味しいからとて貪る心を起こしません。戴きます」

と食前の誓いをしてから箸を取り、朝食を終りて身(心)力満ちたり、いでやこれより午前の作業に奮闘努力せん、御馳走さまと感謝の言葉を捧げる。昼食も同じような誓いをするが、夕食後の誓いは、

「夕食を終りて身力満ちたり、いでやこれより今日の課業を反省し明日に備えん」と唱和する。

そのほかに二月から十二月の修了期までに常用漢字二千を目標に食後必ず二字づつを教えて一日六字を覚えさせることにしている。道場生は大体国民学校出身者であるが、実際に日常語を手紙に書き現すことは出来ないそうで、部落へ帰ってから面事務所などから廻って来る書面を読みこなして部落民に伝えたり、手紙の代筆位は出来るようにとの親心から出た訓育である。

朝食と漢字習得が終ってから午後零時五十分までが第二就業時間で、午後二時から日没七時までの第三就業の時間とともに、道場生に対する皇国農民としての徹底した『鍛える時間』なのである。この日課のうちには、今まで自家にいて、仕方なしに父兄の命令でやっていた農耕に対し再認識を求める時間なのである。暦に従って季節季節の種蒔き、芽生えたならば申しわけの肥料をやり、雨が降らなければ『どうにもならぬ』と諦めて、干害ならばお上のお助けがあるだろうといった他力本願式の営農法を叩き直す時間なのである。雨が降らなければ井戸を掘れ。虫がついたらとれ。肥料が足りなければ堆肥をうんと作れと教え込むのである。

事実この附近の農民は反当百貫、よくて二百貫しか堆肥をやらぬのに、この道場では反当り二千貫の堆肥をやることを絶対の条件として実行している。はげしい日中の農業実習が終って午後八時夕食と食後の行事が終ると、課外として随時に講義や日記記帳、座談会が開かれ九時夜礼、人員点呼、夜の挨拶、家郷に向かっての挨拶があって、九時半、鐘の音と共に十二の農舎は一斉に消灯就寝するのである。

弁口よりも実力

信賞必罰、総て軍隊式

場生の訓練

道場生は十七歳から二十五歳までの青年から選び、二月の入所から四月の農繁期までは専ら集団生活に馴れるための訓育を行うが、本年度の場生は僅か二ヶ月の間にすっかり軍隊式の訓練を会得し、講堂の軒下にある鐘の音一つで同時でも直ちに集合し『××農舎五名異常なし』と報告して全員六十名が瞬時に整列する。

入所した当初は千差万別であった。貧農の子は労働には馴れているが、挙措が粗暴で、甚だしいのは便所の使い方も知らない。自作農の息子は身体が脆弱で役に立たず、これ等を同時に訓練するには軍隊式にやるのが第一である。次には輔導員が道場生の中に溶け込んで、彼等と共に在ることが大切である。陣頭指揮ということは、この道場では、ずっと以前から実行していることで、我々職員は生徒より先に起きて起床の鐘を鳴らし、飯も一緒に同じものを食べるようにしている。それと信賞必罰を厳重にして良いことは大いに褒め、悪いことはびしびしと叱っているが、二ヶ月もすれば軍隊の第一期検閲と同様、どうにか一人前の道場生になる。

食堂兼講堂は俎机の粗末なものであるが、周囲にずらりと第一期から第九期までの修了生の名札がかけてあり、正面には半島農民の父と謳われる我農生、山崎延吉翁の扁額がかかっている。「体裁よりも理想、肩書よりも信念、弁口よりも実力」と書いた言葉は生徒の頭に深く刻みこまれて行くよう、二宮翁道歌と共に輔導員が先唱し合唱して精神修養に努めている。

活眼を開く

道場の特徴

『活眼を開け。眼はただ上っ面のものを見るだけにあるんではない。此処の麥と隣の麥の伸び具合が異なっているが、その原因は何処にあるかをよく見ろ。活眼とは見てよく考えることだぞ』と麥の管理の時、播種のとき、凡ゆる作業実習の際に『物の観方』という点に注意を向けさせる。種を蒔いて稔ったからとて作ったことにはならぬ。それは『出来た』のだ。一生懸命土を可愛がって一本の雑草も畓田になく作物が気持ちよく稔った時に初めて『作った』ということが出来るんだぞーと、この道場の作物に対する考え方は、半島農民が陥りがちな掠奪農業から脱却して土とともに呼吸するという観念を植えつけるのを眼目としている。

また道場生の創意工夫を活かすためには、十二の農舎に付随する畜舎、堆肥小屋、塀などの築造は生徒の勝手な構想の下にやらせている。各農舎とも家長を中心に思い思いの牛小屋を作り、鶏舎の作り方も全部区々であるところに、この道場の特徴が現れている。

十八年度の生産額の予想は一万四千四百三十四円となっており、蔬菜類などは昨年まで一町二反歩を栽培していたのを今年は半分の六反歩に減らして、なお且つ収入は昨年と同じ四千八百円を挙げるように指導している。減反して収入を減らさぬためには投げやりの耕作では駄目だというので、職員の指導で促成栽培を行い、技術によっては収入が殖えることを教えている。現に耕地の一部に紙温室を作って胡瓜茄子の早期栽培をやり、既に胡瓜などは四月十日に一部を出荷している。

農民道場の一日:写真説明:(1)大蔵奉祀殿前の朝礼、(2)食前の誓い、(3)肥料の運搬、(4)畜牛の当番、(5)ペーパーハウスで速成栽培の胡瓜、(6)麥畑の間作に棉の播種=忠南儒城農民道場にて【原田特派員撮影】