A Japanese author took a Busan-Seoul train in 1943 and saw some stylishly dressed young Koreans with a guitar and ‘American vibe’ speaking mostly in Korean mixed with English ‘okay’s, and was shocked that none onboard cared to observe the noon Moment of Silence to honor fallen Imperial soldiers

2023-03-18

657

1148

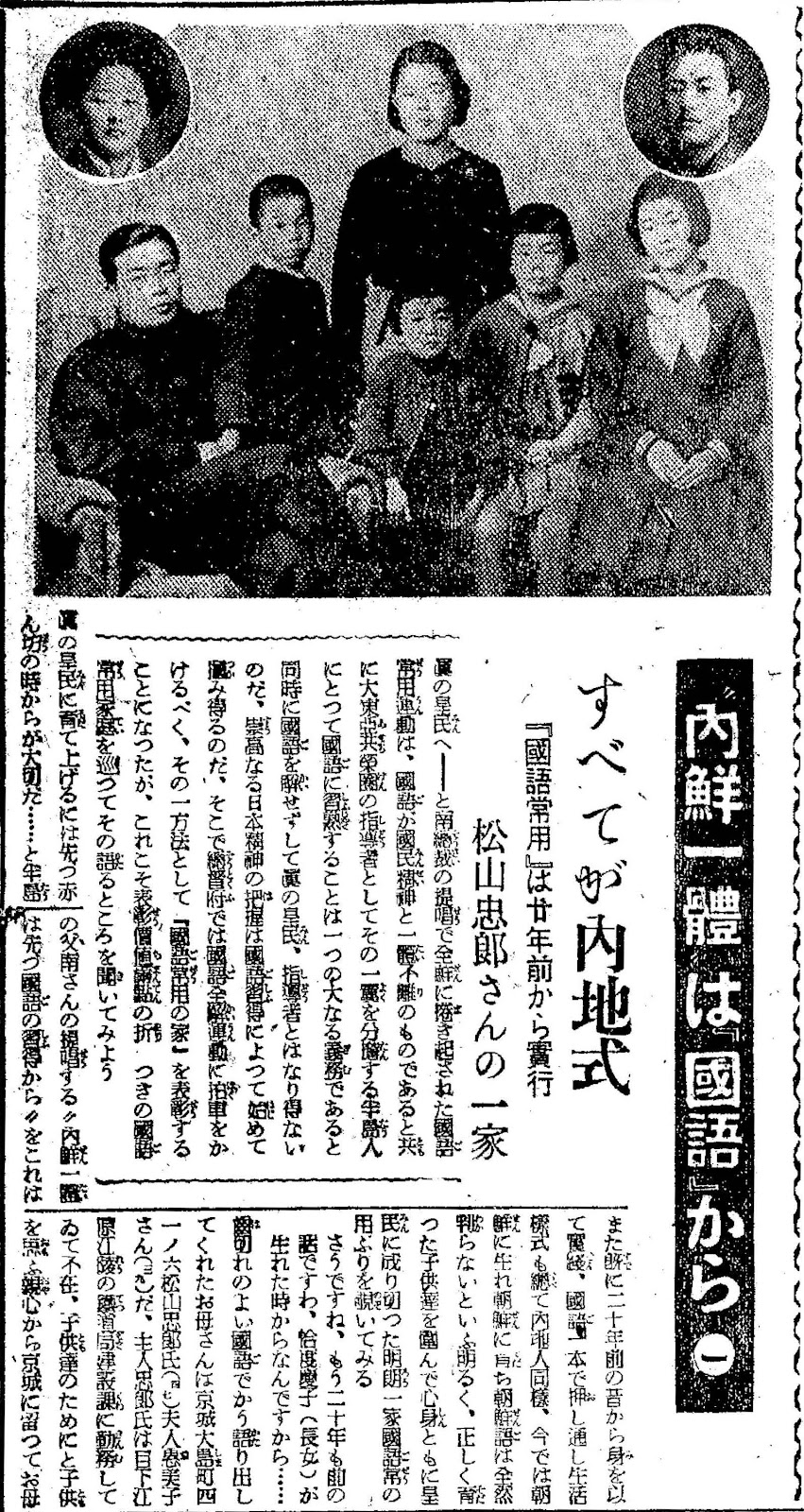

In this article, a famous Japanese author and novelist named Maruoka Akira (1907-1968) takes a trip to Korea in early 1943, writing a bit about his experience taking a train from Busan to Seoul, in which he encountered a group of 7 or 8 young Korean people wearing stylish Western clothes and having an ‘American vibe’. The only woman in the group wore the latest Ginza fashion, while the men wore flat caps which reminded the author of American movie stars. The author thought it was notable that they mostly spoke Korean with some Japanese and interspersed with the English word ‘okay’. He was shocked to find that neither the Japanese nor the Korean train passengers cared to observe the Moment of Silence at noon to honor fallen Imperial soldiers.

In August 1943, this would all change with silent prayers in trains becoming more vigorously enforced. In September 1943, the young Koreans would no longer be able to wear their stylish clothing in public with the passing of onerous clothing regulations enforcing a wartime minimalist fashion.

This article also features a travel story from Mr. Nobuyuki Tateno, a Keijo Nippo correspondent who also covered a 1944 story about Korean parents who picked up their son’s remains at a military facility in Japan. He observed young Koreans boys being forced to work in Pyongyang at Pothong river using a Mokko sling, which was a woven net traditionally used to carry heavy materials (dirt, rocks) in construction projects. The boys belonged to an Imperial Training Institute, which eventually became more of a source of cheap labor than a place to ‘train’ Koreans into becoming ‘true Imperial subjects’.

Also mentioned are other similar brainwashing institutions for indoctrinating Koreans with Imperial Japanese state propaganda, such as farmers’ dōjōs, women’s training centers, Imperial dōjōs, and Yamato cram schools. They have been covered in detail by other Keijo Nippo articles that I have previously translated, so I have provided links throughout the articles.

(Translation)

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) June 9, 1943

How the powerful Korean Peninsula was viewed by mainland Japanese visitors

Expressions of determination on the faces of the youth fueled by hope

Mr. Nobuyuki Tateno’s Story

I felt that the situation in Korea had brightened when I saw the farmers’ dōjōs, the women’s training centers, and the Imperial dōjōs in the suburbs of Pyongyang. In Pyongyang, people below the conscription age are being gathered, and they are making efforts to grasp the Imperial spirit in the course of doing manual labor. I saw history-making expressions of determination on the faces of the boys carrying Mokko slings at Pothong river. I realized how the announcement of the conscription system had brightened the lives of the Korean youth, and the announcement had indeed been made at the most appropriate timing.

It makes me feel uncomfortable whenever I hear mainland Japanese people who pretend to know so much, telling me things like, “That’s not something that you can understand just by taking a two-week trip”. Whenever I see old Korean men and Korean women visiting and worshiping at Shinto shrines, I think about how well their leaders have managed to guide them up to this point, and I feel as though I have just witnessed a great historic leap forward. When I saw Sup’ung Dam and learned that its construction had gone very smoothly, I thought that this accomplishment silently attested to the success of the leadership.

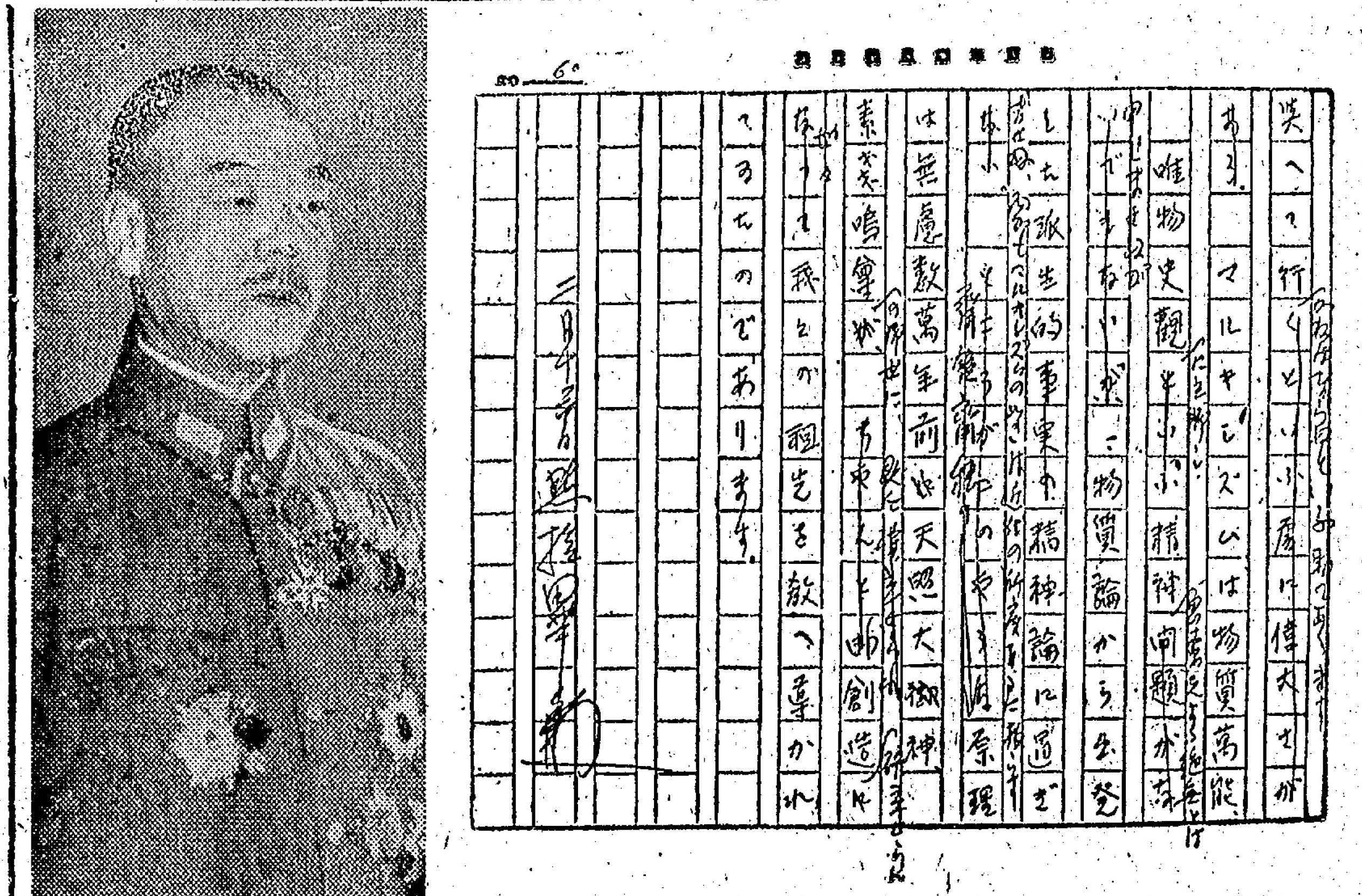

Mr. Akira Maruoka‘s Story

I think there is a great gap between what I heard from my acquaintances living in Korea and what I actually saw in Korea during my visit. I was surprised when I arrived in Busan. I really got the feeling that continental East Asians truly lived here. There was this ‘continental feeling’ that was different from what I felt when I visited Sakhalin and Hokkaido. It made me realize that Korea was really at the edge of a continent that stretched to the Soviet Union, Germany, and Turkey.

When the train stopped, I felt a sense of quietude, which was a kind of a continental quietude that could not be felt in mainland Japan, and it made me feel a sense of harmony. I thought that this was the kind of place where continental East Asian people could relax.

Below, I will just describe what I felt without drawing any conclusions.

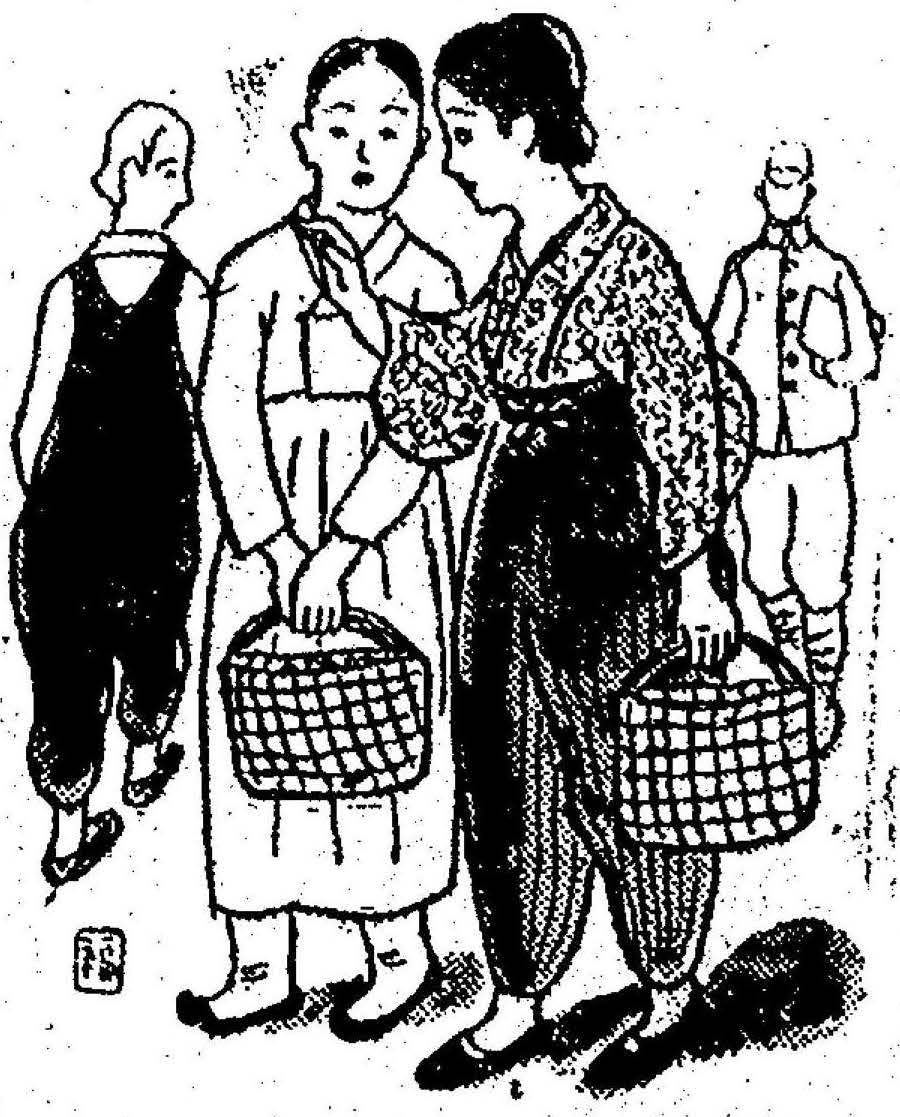

◇...When I was on a train, and there were seven or eight people in a corner who were very stylishly Westernized. They were Koreans. Among them was a woman. At first I thought she was a mainland Japanese woman, but it turned out that she was a Korean woman from around here. They all had an American vibe. The woman was dressed in the same fashion that you would see in Ginza. The men wore flat caps and looked like American movie stars. There was a guitar on the shelf, so I thought they were musicians who played light music. They spoke in Korean, but they occasionally tried speaking in Japanese, and sometimes they even deliberately said “Okay” in English.

◇...When I arrived at a certain train station, the station staff informed us that it was time for the Moment of Silence. A few station staff members stood up and prayed silently. I also stood up and prayed silently, but no one else stood up to observe the Moment of Silence, neither the mainland Japanese people nor the Korean people who were riding in the train. I had been told in mainland Japan that they observed the Moment of Silence on the Korean peninsula, and that it would be a very beautiful scene to behold, so I felt surprised.

◇...When I was eating my lunch on the train, I gave a boiled egg to a Korean child of about five or six years old who was sitting in front of me. The child’s mother seemed to be instructing the child to say “Thank you” but the child didn’t say anything.

◇...When the train was crowded, a young Korean man took a seat next to me. After he went to the bathroom, a young woman came and took a seat in his place. When the man came back from the bathroom, he did not say a word to the woman, but continued his cheerful conversation. In mainland Japan, when you go to the bathroom, you are supposed to put your hat on your seat or something, and if your seat is taken, you are supposed to say something about it, but he didn’t say anything and continued his conversation. I thought that was strange.

◇...In Seoul, I visited Yamato Cram School, where I saw young people who could be called the wings of the future. [END]

Source: https://www.archive.org/details/kjnp-1943-06-09

(Transcription)

京城日報 1943年6月9日

総力半島は如何に視られたか

“生き抜かん”表情、希望に燃ゆる青少年

立野信之氏談

農民道場や女子訓練所或いは平壌郊外の皇民道場等を視て朝鮮の動きが明るくなったことを感じた。平壌では徴兵適齢前の者を集め、労働のうちから皇民精神を掴むことに努力している。普通江でモッコを担ぐ少年の顔を見ると、歴史的なもののなから生き抜かんとする表情がある。これらをみて徴兵制の発表が如何に半島の青少年を明るくしたことかを知った。最も良き時期に発表したものである。

内地で聞くことであるが、『僅か二週間やそこいらの旅行で判るものではない』などと如何にも知ったか振りの人の言葉を聴くと私は実に不快に思う。神社に参拝する朝鮮の老人や婦人をみると、指導者はよくぞここまで導いた、ということを考え、歴史的飛躍を感ずるのである。水豊ダムを観たとき、その建設は非常に順調に進んだと聴き、これは無言のうちに指導の成果を語るものであると思った。

丸岡明氏談

朝鮮に住んでいる知人から聴いたことと、今度私が視た朝鮮は非常にひらきがあると思う。私は釜山に着いたときからビックリした。東洋人が住んでいるという感じであった。これは樺太や北海道に行ったときに感じたものとは違う大陸的な感じである。朝鮮はソ連にドイツに、トルコに通ずる大陸の端であると思った。

汽車のなかで感じたことであるが、汽車が留まると車内は実にシーンと静かさを感ずる。この静かさは内地では感じられない自分が和になる大陸的な静かさであった。東洋人の憩う場所はこんな處だと思った。

以下、結論を抜きにして感じたままを話そう。

◇...汽車の中での話だが、隅の方に七八人のハイカラな人が居た。朝鮮の人である。このなかに一人の女が混ざっていた。最初は内地の女だと思ったが、やはりこちらの女であることが判った。みんなアメリカ的な感じである。女は銀座などでみるのと同じような服装。男は鳥打帽を被りアメリカ映画の二枚目のような感じである。棚の上にはギターがあるので、軽音楽でもやる人達かと思った。言葉は朝鮮語である。たまには国語で話してみたり、なかにはことさら『オーケー』などといってみたりしている。

◇...或る駅に着いた時の話である。黙祷の時間を駅員が知らせている。そして僅かな駅員が立って黙祷をする。私も立って黙祷をしたが、乗っていた内地人も半島人も誰も立たず、黙祷もしない。内地で聴いたことによると、半島には黙祷の時間があり、非常に美しい場面がある、と知らされていたが、これはと思った。

◇...汽車のなかで弁当を食う時、前に掛けていた五つ六つくらいの半島の子供へ私はゆで卵を一つ与えた。その子供の母親らしいのが『有難う』をいえと訓えているようだったが、その子供はなんともいわなかった。

◇...列車内が混んでいる時だったが、半島の青年が私の横に席をとった。その男が便所に行った後、或る若い女がきてそこへ掛けた。男は便所から帰ってきてもその女には小言も言わずに朗らかに語っていた。内地では便所に行くときには自分の座席へ帽子を置くとか何とかするものであり、座をとられれば何とかいうのだが文句もいわずに朗らかに語っているのだ。私は不思議に思った。

◇...京城で大和塾を観たが、そこにはこれからの翼ともいうべき若き人達をみた(おわり)