Annie Ellers Bunker, American missionary who went from personal physician to Empress Myeongseong to thriving philanthropist in Colonial Korea, was praised in this 1938 Keijo Nippo obituary for endorsing the Imperial Japanese Army

2023-11-14

464

2102

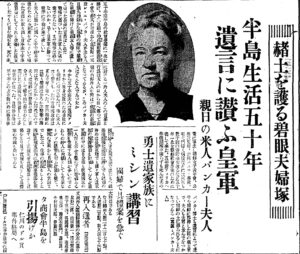

This obituary from October 1938, published in Keijo Nippo newspaper, an organ of the Imperial Japanese colonial regime which ruled Korea from 1905 to 1945, features Annie Ellers Bunker, an American Methodist missionary and physician who spent around 50 years in Korea. This article sheds light on her remarkable journey, from being Empress Myeongseong’s personal physician to her involvement in colonial Korea’s society.

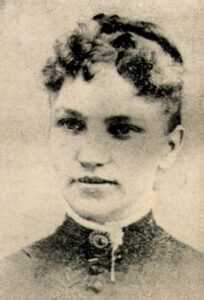

Born on August 31, 1860, and passing away on October 8, 1938 (exactly 43 years after the assassination of the Empress), Annie’s life spanned significant historical events. Her role as the personal physician to Empress Myeongseong, especially leading up to the Empress’s assassination in October 1895, granted her intimate access to the royal court. After the annexation of Korea by Imperial Japan, she seemed to prosper, raising thousands of yen to support various institutions including the Korean Young Women’s Christian Association, Gongju Orphanage, Gongju M&A School, and Dongdaemun Women’s Hospital. This indicates her significant influence in colonial Korea.

Interestingly, her last words before her death in 1938 were “I wish the Japanese Army will win soon and bring peace to the East”, raising questions about her possible pro-Japanese sentiments, even during her time as the Empress’s physician. Given her intimate access to the royal court at the time of the Empress’s assassination, her documented pro-Japanese sentiments, and her subsequent successful career as a philanthropist in Korea under Imperial Japanese rule, it naturally raises a delicate question: could she have had any involvement or knowledge regarding the Imperial Japanese conspirators who assassinated the Empress? This is a matter left to historians to ponder, and it is not my intention to accuse Annie Ellers of any wrongdoing but to highlight the complexities and controversies surrounding her life.

Annie’s closeness with Empress Myeongseong is further highlighted by an incident where, upon her marriage to Dalzell Bunker, the Empress demanded to see her wedding dress, examining it meticulously.

Annie’s impact extended to nursing in Korea, being the first female medical missionary in the country. A Boston University Medical College student, she arrived in Korea in 1886, founded the Chungshin Girl’s School, and became a trailblazer in women’s healthcare and education.

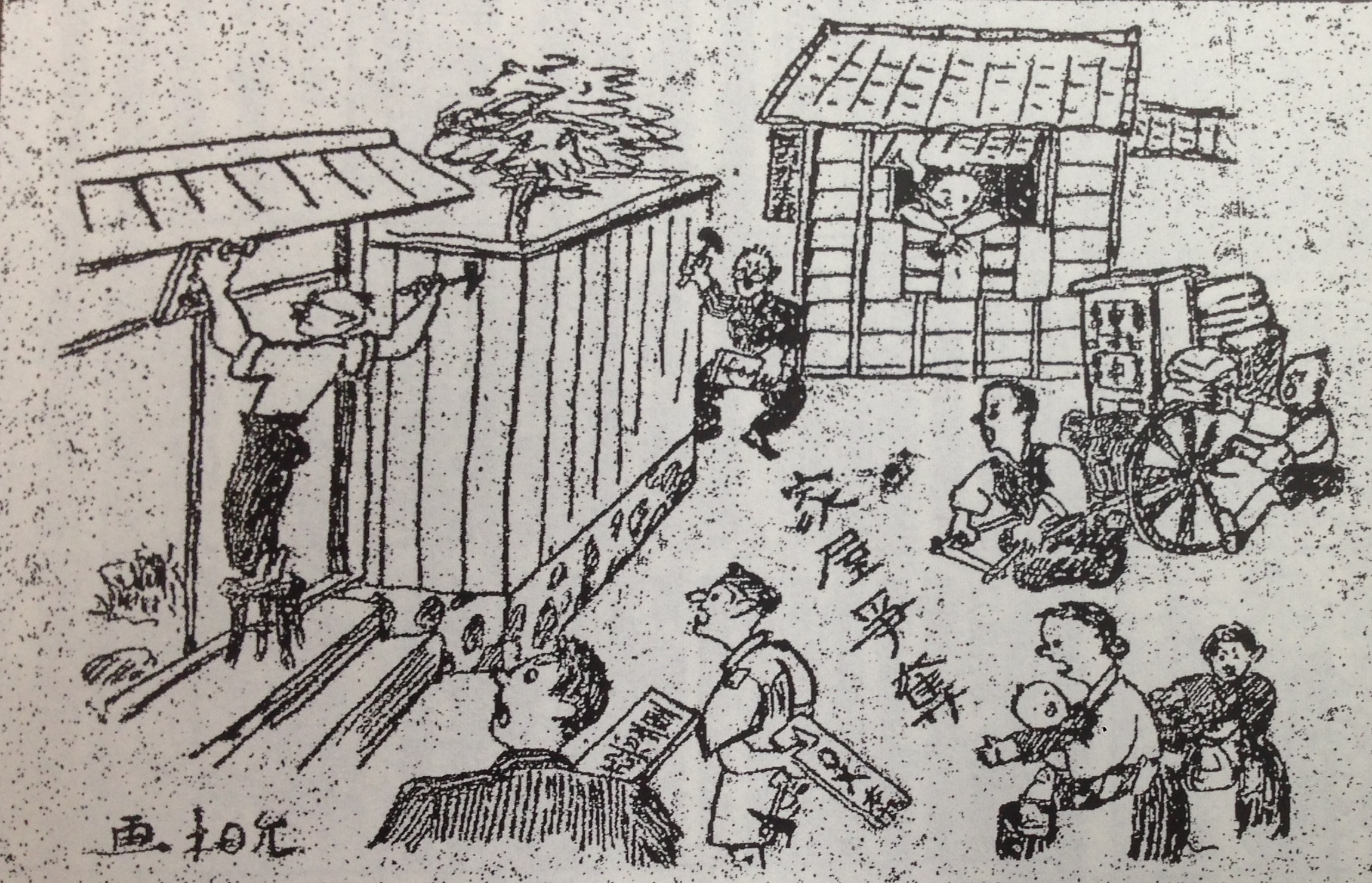

In 1938, the colonial authorities took over the Chungshin Girl’s High School, which she founded, and converted it into a state-controlled school promoting State Shintoism and imposing the Japanese language.

Her first encounter with the Empress is vividly documented in her personal essay published in the Korean Repository, a journal for foreign Christian missionaries published between 1892 and 1899. This account provides a fascinating glimpse into her life and the complexities of her role in Korea. For the sake of improving accessibility, I have transcribed and posted the entire essay below, originally found in a PDF from the Korean Repository which is not OCR enabled.

Annie Ellers Bunker is now buried at the Yanghwajin Foreign Missionary Cemetery in Seoul, where her grave marker notes her 40 years of service as a missionary in Korea, until 1926.

This story is not just about the life of a missionary or a physician; it’s about a woman whose life intersected crucial historical events, raising questions about her beliefs and the impact she had on Korean society.

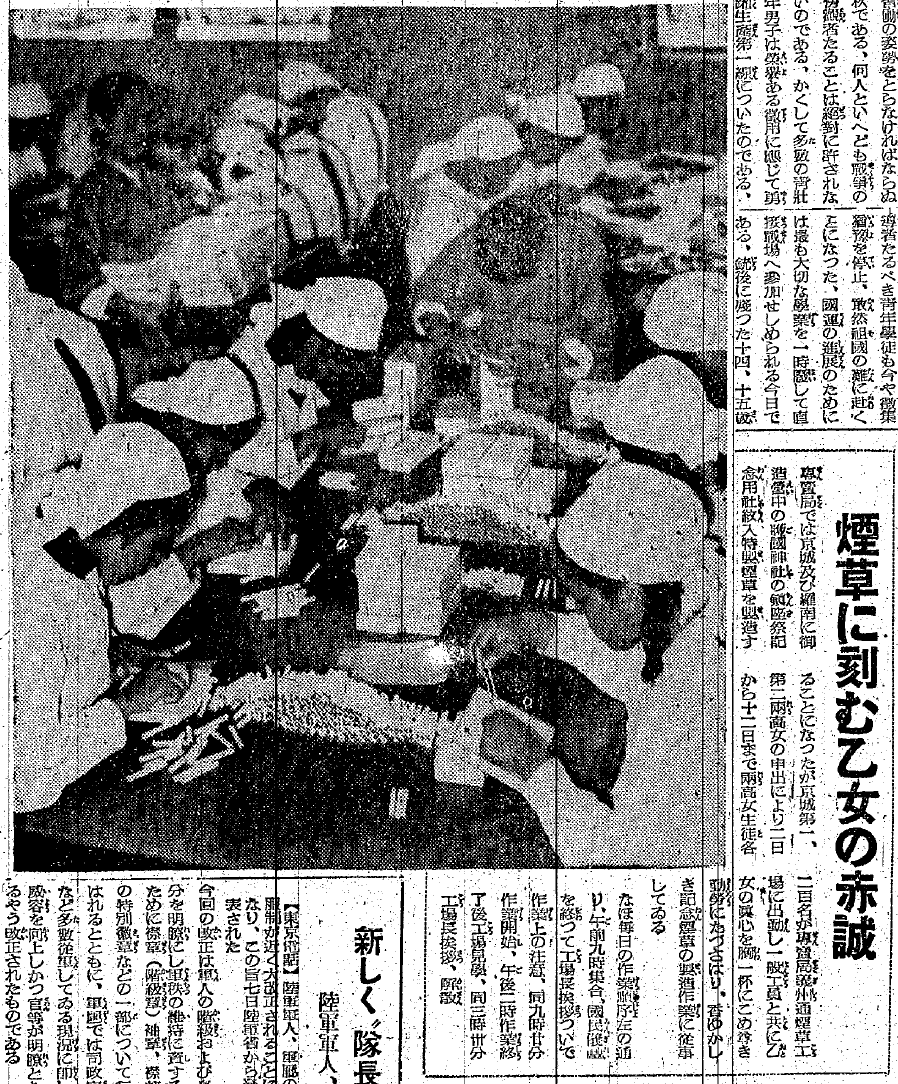

[Translation]

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) October 12, 1938

The Grave of the Blue-Eyed Couple Guarding the Red Earth

- Fifty Years of Life on the Korean Peninsula

- Her Last Testament Praises the Imperial Army

- Pro-Japanese American Mrs. Bunker

The deceased Mrs. L. A. Bunker, who dedicated her life to social work on the Korean peninsula for fifty years, will have her funeral at the Chungdong Methodist Church at 10 am on the 12th at 13 Jeongdong-gil. Her last words, spoken to relatives and friends offering solemn prayers at her peaceful deathbed at 9 am on the 8th, were these: “I feel terribly sorry for the wounded Japanese soldiers on the battlefield. Why isn’t the war over yet? I wish the Japanese Army will win soon and bring peace to the East.”

With a trembling hand, Mrs. Bunker took out the remaining hundred yen from her entire fortune, which she had dispersed for charitable causes, and requested it be used as a fund for the Japanese Red Cross. Then, she closed her eyes in peace. The words and actions of this foreign lady on her deathbed are being passed from mouth to mouth among friends, stirring deep emotion among the Japanese, Koreans, and foreigners in Seoul.

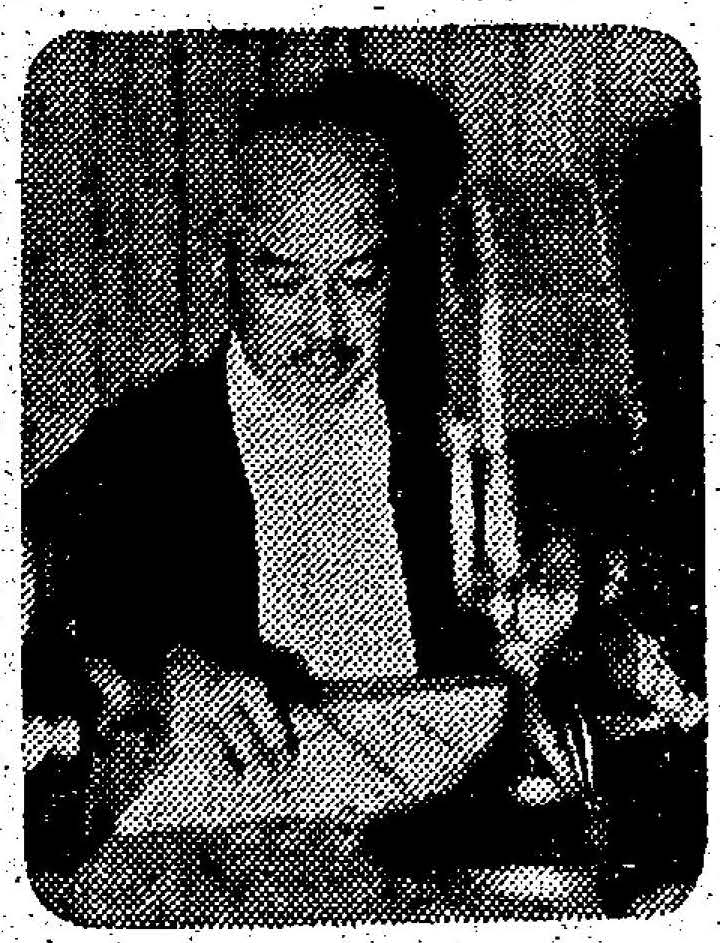

But who was Mrs. Bunker? Fifty years ago, she bravely came to Korea from her native America alone for missionary work. Fortunately, being a female doctor, she was warmly welcomed by the Korean government. At that time, there were hardly any Western medical facilities in Korea, so Mrs. Bunker, as a pioneer in Western medicine in Korea, dedicated herself and served for many years in the palace as the personal physician to the deceased Empress Myeongseong. After the annexation of Korea by Japan, she focused on missionary and charitable work for thirty years, contributing thousands of yen to various institutions such as the Korean Young Women’s Christian Association, Gongju Orphanage, Gongju M&A School, and Dongdaemun Women’s Hospital, dedicating her life to social work in Korea for fifty years. Five years ago, her husband Dr. Bunker died while she was on holiday in America. Her husband was so pro-Japanese that he requested in his will to have his remains moved to Korea. Mrs. Bunker, too, will be buried in the beloved Korean soil alongside her husband. [Photo: Mrs. Bunker]

[Transcription]

京城日報 1938年10月12日

赭土を護る碧眼夫婦塚

- 半島生活五十年

- 遺言に讃う皇軍

- 親日の米人バンカー夫人

五十年間半島の社会事業に一生を捧げ、十二日朝十時貞洞町監理教教会で葬式が行われる貞洞町一三故レ・エ・バンカー夫人が去る八日朝九時、静かな臨終の病床で厳粛な祈祷を捧げる親戚友人等に遺して去った最後の言葉はこれだ。

「戦場に傷ついた日本軍人が気の毒でならない。まだ戦争が終らないのか。早く日本軍が勝って東洋に平和が来て欲しい」と夫人は微かに震える手で慈善事業のために全財産をばらまいて残った百円を取り出し日本赤十字事業資金にしてくれと依頼した後、安心したように目を閉じた。死の床に於ける一外人夫人のこの言葉と行為は友人の口から口へ伝わって在城の内鮮外人を問わず感激の話題となっているが、このバンカー夫人はどんな人であったか。

今から五十年前、夫人は故国アメリカから単身宣教のため、勇敢にも朝鮮に飛び込んだ。幸いに夫人は女医でもあったので韓国政府は喜んで厚く迎えた。当時朝鮮はおろか洋医薬の施設は殆どなかった時代なので、夫人は朝鮮に洋医術を済した草分けとして献身的な努力をなし選ばれて故閔妃の侍医として多年宮中に仕えた。日韓併合後は三十年この方布教の外に慈善事業に専念し、朝鮮女子青年会、公州託児所、公州エムエー学校、東大門夫人病院などには何れも数千円の寄付金をおくるなど五十年一生の朝鮮社会事業のために尽くして来た。五年前アメリカへ休暇帰国中図らずも死んだ夫のバンカー博士も遺言によって遺骨を朝鮮に移葬した程の親日家で、夫人も夫君と並んでなつかしい朝鮮の土に葬られることになっている。【写真=バンカー夫人】

Source: https://archive.org/details/kjnp-1938-10-12/page/n9/mode/1up

[The Korean Repository, October 1895, pp. 373-375.]

My First Visit to Her Majesty, The Queen

During the visit of Mrs. H. G. Underwood and myself to Her Majesty on the 14th of September we saw the Queen Dowager and she gave us each a handsome gold-embroidered chumoncy or purse-Our visit to Her Royal Highness was in the same place where some years ago I went to see the Queen. Many changes have come since then and the Queen now lives in a new building, beautifully lighted with electricity, in another part of the grounds.

It is just nine years ago this fall since I was first, in company with Dr. H. N. Allen the King’s physician, called to visit, Her Majesty, the Queen. She had been ill for some time and they had sent to Dr. Allen for medicines. As there was no improvement in her condition the Doctor assured them, that, in order to treat Her Majesty properly, she must be examined, and so the writer was called.

It was a lovely autumn day, when in the early afternoon, we started for the Palace in our sedan chairs, with our keysos (soldiers) running ahead and clearing the way. My heart was thumping vigorously and I wondered how I would be received, half fearing the ordeal.

On our arrival at the outer side-gate of the palace wall, we had to get out of our chairs and walk quite a distance, about a quarter of a mile, I should judge, to the Reception Hall. As we neared the place we were met by Prince Min Young Ik whom I had met, and who, having travelled much, knew something of the customs of foreigners.

He showed us some of the beauties of the palace grounds and after our walk around the artificial lake, he escorted us to the waiting-room and there had us served with foreign food, Korean fruit and nuts.

Soon a messenger dressed in court costume came for me and, Prince Min accompanying me, we started for the Audience Hall. We first crossed a large open court, which I noticed had large potted plants around three sides of it but not a spear of grass growing in it anywhere. Ascending a flight of broad stone steps, crossing the narrow verandah and stepping over a high door sill, I found that we were at one end of a long, wide hall, the floors of which were covered with the soft, beautiful, figured Korean matting which is such a fine article and so hard to obtain. At the farther end of the hall, I saw a large number of Koreans, men, women, and young girls. I made my three bows as I advanced and then found myself in front of the company among whom I soon singled out Her Majesty and for the rest of that visit I had eyes for no one but her. In later visits I learned to distinguish the gentlemen from the eunuchs, and also the ladies-in-waiting by their peculiar head-gear and their fine skirts of silk gauze. The immense chignons worn by these ladies are objects of wonder not only as to size but also as to how the intricate windings and braidings of the glossy strands is accomplished. One evening while witnessing some of the delightful and peculiar posture-dancing done by the dancing girls at the palace, I asked one of them if her chignon was not heavy – “Oh, said she, it is very heavy and makes my head ache.” These head dressings vary in shape; sometimes they are long and narrow and then again they have large lateral loops.

The Queen, beautifully dressed in silk gauze skirts, with strings of pearls in her raven locks, a lady, short of stature, with white skin black eyes and black hair, greeted me most pleasantly. She had on no enormous head dress but only her own glistening locks twisted in a most becoming know low down on her neck. She wears on the top of her forehead her Korean insignia of rank. All the ladies of the nobility wear a similar decoration but of inferior quality and workmanship. To me the face of the Queen especially when she smiles, is full of beauty. She is a superior woman and she impressed one as having a strong will and great force of character, with much kindliness of heart. I have always received the kindest words and treatment from her and I have much admiration and great respect for her. After first asking if I were well, how old I was, how my parents were, if I had brothers and sisters and how they were, she proceeded to tell me that they had been told by Dr. Allen of my arrival in Korea, that she was much pleased at my coming and hoped I would like the country. All of this conversation was carried on through an interpreter who stood, with his body bent double, back of a door where he could hear but not see.

Prince Min, who had been standing by, now had a chair brought for me and I noticed that back of Her Majesty there was a foreign couch. The Queen telling me to be seated sat down on this couch and then the medical part of the interview began.

I had noticed that two gentlemen had seated themselves when the Queen sat and when I got up to leave, they with Her Majesty rose and returned my bows.

Prince Min conducted me back to the waiting room and there I waited for Dr. Allen who was having an audience with His Majesty. When he returned I learned from him that both the King and Crown Prince had been present during my interview. I was very glad that I had not known who the two gentlemen were, for I fear my composure would not have been even such at it was. After being served with more food and fruit we were each given a certain number of soldiers to accompany us home and also, as it was dark, lantern bearers. The sight of the Korean lantern with its outer covering of red and green silk gauze is very picturesque and as we passed, many a dusky head peeped out through opened doors and windows to see what it all meant. The empty dark streets with the dark low houses on either side, the lantern bearers of the Doctor’s chair and of mine with the attendant soldiers, carrying their rifles made a picture at once interesting and unique. In recent visits we are permitted to go through the large front gate into the grounds and right up to the waiting room door. Upon arriving here tea, coffee, and fruit are served and then we are called in to Her Majesty, who receives us in one of the smaller private appartments. The King and Crown Prince are always present. After the interview we are permitted to proceed home immediately.

Annie Ellers Bunker