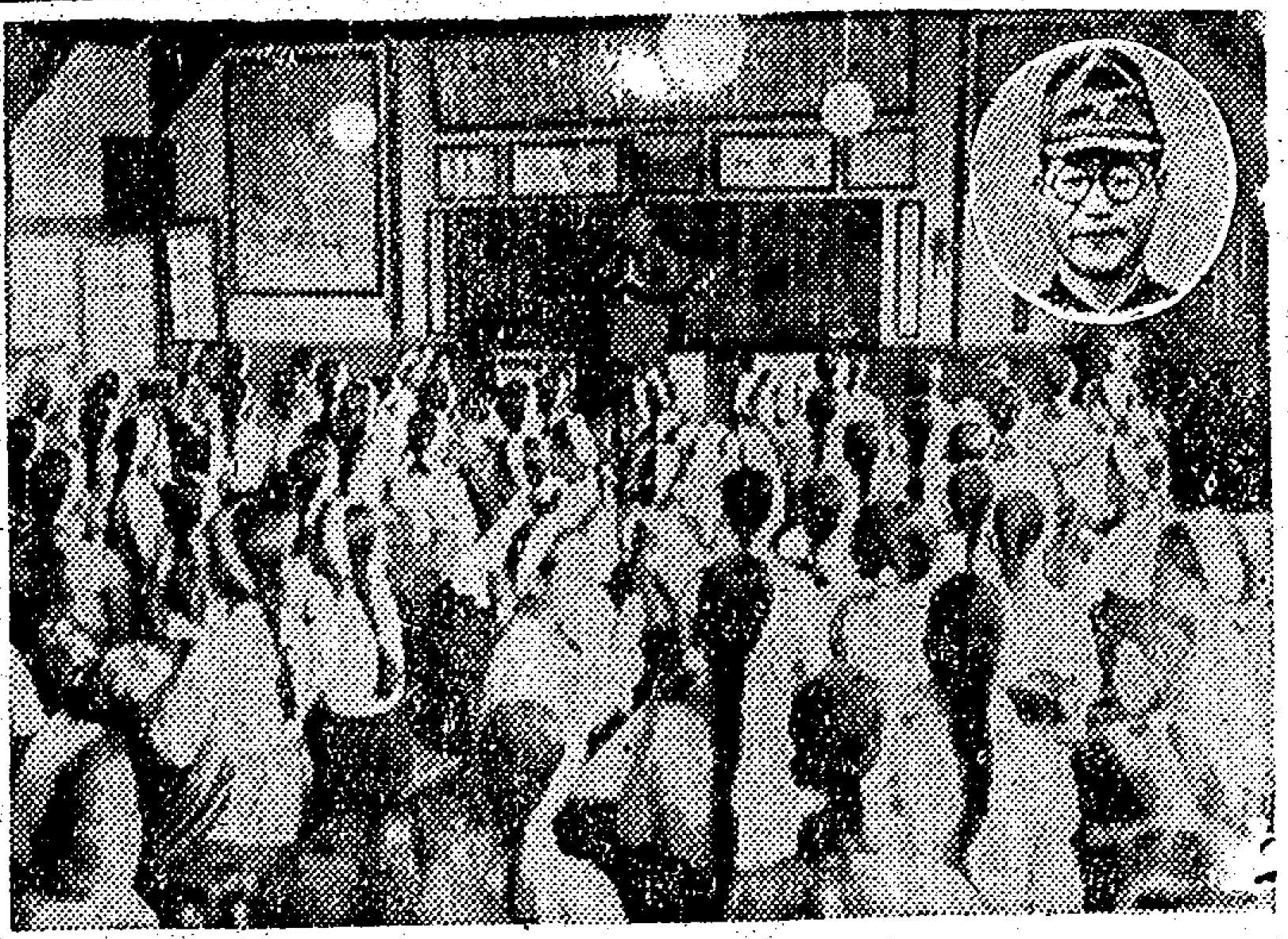

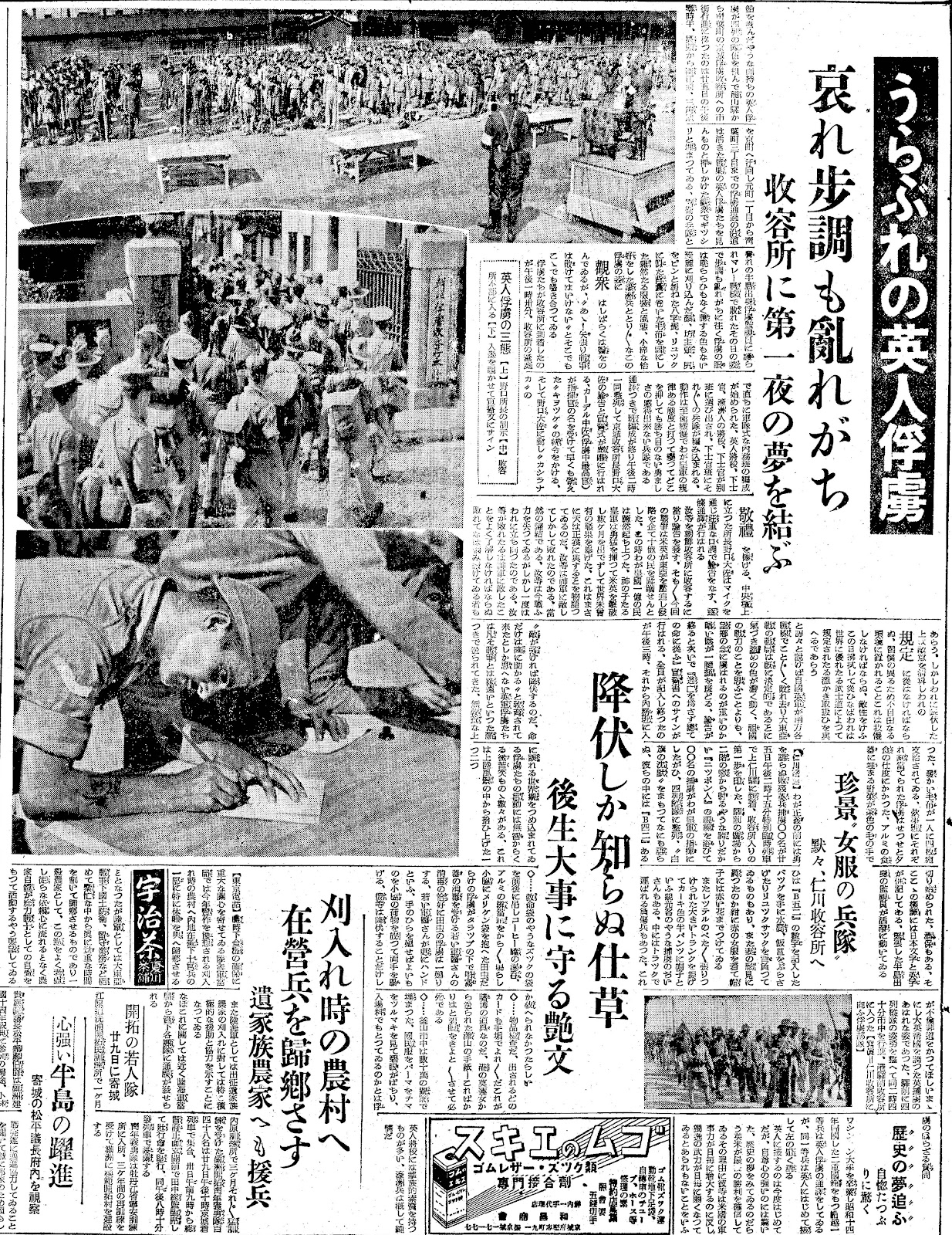

February 1943 news article of British prisoners of war interviewed by their Imperial Army captors in Keijo (Seoul) POW camp

2023-12-16

554

2110

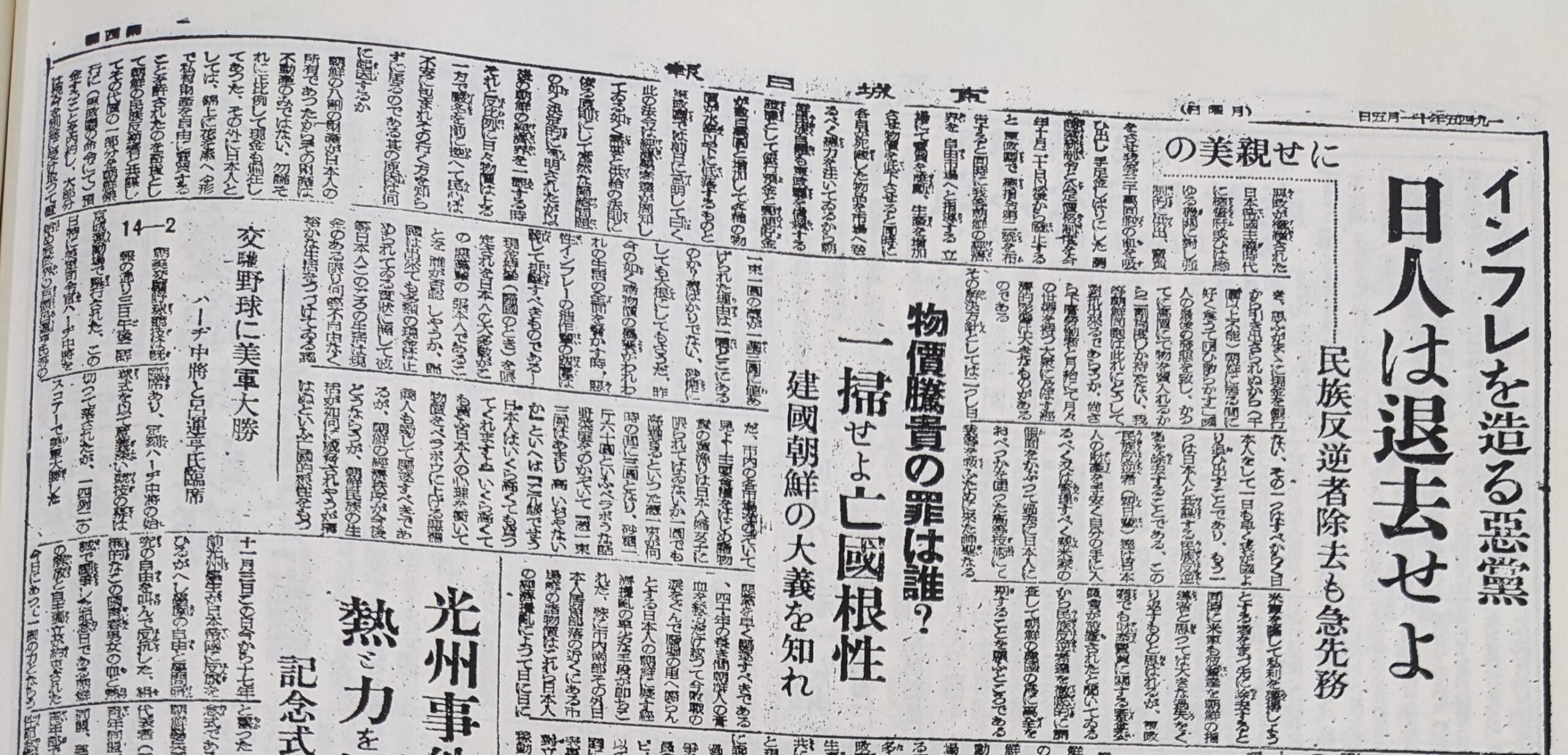

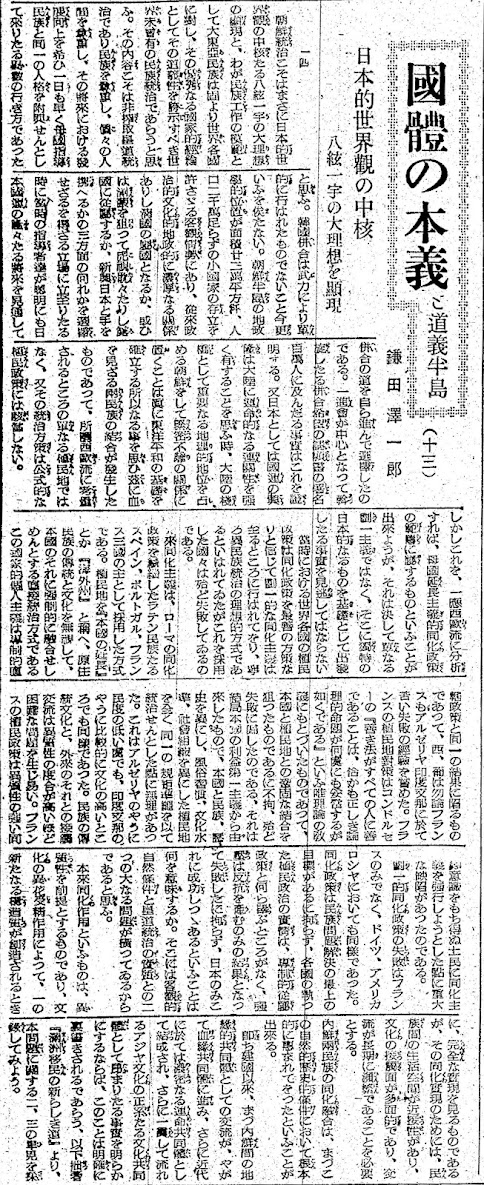

This is a news article from February 1943, published in Keijo Nippo newspaper, an organ of the Imperial Japanese colonial regime which ruled Korea from 1905 to 1945, featuring an interview with British Prisoners of War who were held captive in Seoul (then called Keijo in Japanese) during World War II. For this post, I co-partnered with Richard Baker, an independent researcher who is currently writing a book on the experiences of the POWs who were shipped to Korea for propaganda purposes. He also has a Master’s by Research postgraduate thesis on Keijo camp which can be found at this link: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/72789/

[Translation]

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) February 15, 1943

The Day Singapore Fell

Listening to the British Prisoners of War

The Superior Attack of the Imperial Army

Deep Gratitude for their Fair Treatment

The Dawn of Greater East Asia. It has been a year since Singapore, the proud bastion of the British invasion of East Asia, fell on that significant day in history. On February 15, 1942, at 7 PM, our General Yamashita met with the enemy General Percival. With decisive words from General Yamashita demanding a “Yes or No” answer, Percival signed the unconditional surrender at 7:50 PM with his trembling hand. The fierce battle for Singapore, breaking through the jungle and trudging through the mud, ceased here. This day is celebrated as “The Fall of Singapore”.

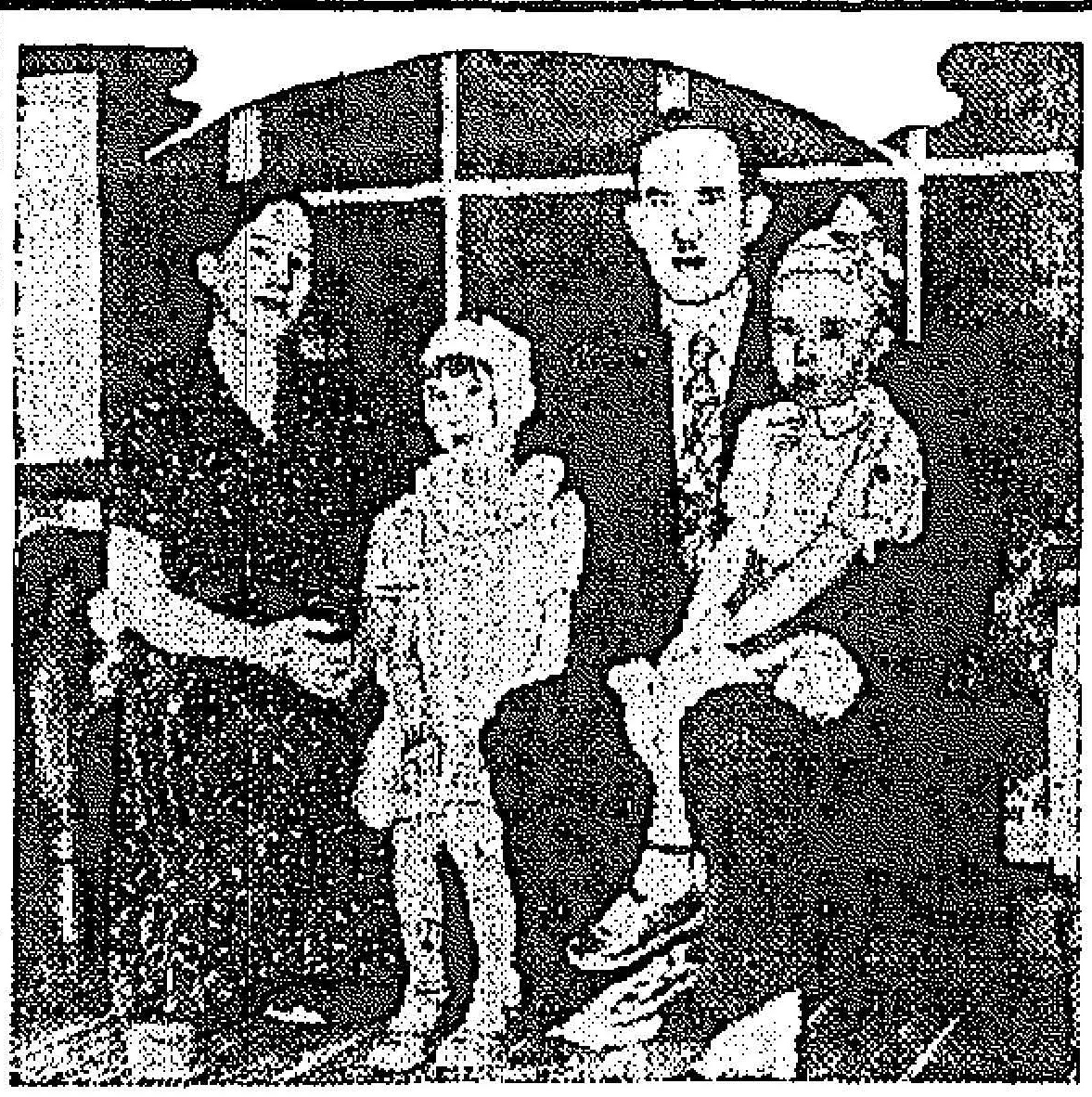

The interviewed British Prisoners of War:

- Commander of the 2nd Battalion, Loyal Regiment: Colonel Elrington (age 45)

- Company Commander of the same, Major Leighton (age 33)

- Adjutant of the 2nd Battalion, Captain Paque (age 36)

- Attached Warrant Officer of the 3rd Company: Moffat (age 39)

- Mortar Company Sergeant and Platoon Leader: Sergeant Strange (age 29)

- Platoon Leader of the 1st Company, 2nd Battalion, Loyal Regiment: Lance Corporal Ankers (age 31)

Q: When did you start preparing for defense on the Malay Peninsula? And how long did you think Singapore would hold out?

Colonel Elrington: My battalion was transferred from Shanghai to Singapore on April 6, 1938. We thought Singapore would hold out forever.

Q: Can a non-commissioned officer become a platoon leader in the British Army?

Sergeant Strange: Normally, it is an officer’s position, but when my unit moved to Malaya, our platoon leader was injured, so I took over.

Q: Where were you captured during battle?

Captain Paque: We were not captured. We were told by Commander Percival to lay down our arms.

Q: Where were you at that time?

Captain Paque: I was in the Gilman Barracks in the Alexander area.

Q: How was the battle against the Japanese forces?

Colonel Elrington: On February 8th and 9th, the Japanese attacked from the northeast and northwest, but we didn’t know where the attack would come from. There were no defense facilities on the west coast before the war. The Australian and Indian troops confronted the Japanese here, and after two days, we were pushed back to Bukit Timah. Our battalion was ordered to move from our barracks to Bukit Timah on the 10th, and we held our position near Bukit Timah until the night of the 12th. On the 12th, we saw Japanese troops breaking through the jungle and moving behind us. These Japanese troops were excellent soldiers.

On the 13th, we received orders to retreat to Buonavista, and that night we fell back to Alexander Road. At that time, the Japanese army was advancing rapidly along roads of Bukit Timah with tanks and infantry. On the 14th and 15th, our battalion defended the Gilman Barracks while being attacked by Japanese artillery and from the air. This battle was the closest we had fought.

We were astonished by the fierce attack of the Japanese. There were bayonet charges by Major Leighton (2nd Company) and Warrant Officer Moffat (attached to the 3rd Company) until the evening of the 14th, but against the Japanese charging with bayonets, our team could only counter with machine guns. No matter how much we shot, the Japanese soldiers kept coming like little demons. It felt like they were not human. In this fierce battle, only a few members of our 2nd and 3rd companies survived.

Our battalion’s left wing had a Malay battalion. The Japanese broke through there and took control of the sea near the left wing. I had to order the next line of defense to be set up on Washington Hill as the battalion commander. This was between 2 and 3 PM on the 15th. At 8 PM, we received an order from General Percival for everyone to surrender. The next day, a Japanese officer came and praised the Loyal Regiment for its bravery.

Captain Paque: Our first encounter with the Japanese army was on January 14 in Segamat. We were bombed, but it was not a battle, we retreated. The Japanese Army we were facing at that time had beautifully broken through the rubber plantations and the jungle, coming around the sea to our rear.

Colonel Elrington: In the battle at Payong, between Muar and Yong Peng, seven Japanese tanks appeared, and the infantry advanced.

Major Leighton: The Japanese tanks broke through the normal barbed wire and anti-tank mine obstacles, but there was no engagement, and we retreated on that day.

Warrant Officer Moffat: We could never predict the actions of the Japanese army; they always came around from behind, forcing us to retreat. The Japanese Army was very good at mobile operations.

Colonel Elrington: We had lost 40% of our soldiers by the time we retreated to Singapore. We arrived in Singapore by truck on the 26th and were re-equipped as a reinforcement unit.

Warrant Officer Moffat: When crossing Johor, we had not yet seen the Japanese army.

Q: How did you feel when Singapore fell?

Colonel Elrington: I was surprised when I received the order to surrender. We did not anticipate this. We had fought with all our might, but there was no choice once the order was received.

Q: How did you feel when you heard that the Japanese army had landed in Singapore?

Colonel Elrington: I expected it at that time.

Captain Paque: We were prepared to fight until we were all killed, but there was no choice once the order was received.

Q: What do you think was the cause of the fall of Singapore?

Colonel Elrington: The facilities for defense against attacks from the north were not sufficient. Singapore was defended facing the southern sea. Also, the air force was very weak. The direct cause of the surrender was “to avoid civilian casualties and destruction of the city, as the Japanese army had taken control of the water supply,” as General Percival said.

Lance Corporal Ankers: The Japanese army was numerically superior, and their air bombing was skilled; we were just defending our position.

Sergeant Strange: I was injured in the hand by a rifle bullet during the battle at the Gilman Barracks. I still have that bullet as a souvenir.

Colonel Elrington: The Japanese army was good at mobile operations like breaking through the jungle and attacking unexpectedly.

Q: So, are you saying that the Japanese Army’s attack through the jungle and mud, striking from unexpected places, was ungentlemanly?

Colonel Elrington: No, no, that is not the case. In our army, the motto is “All is fair in love and war.” The Japanese Army’s attack was excellent.

Q: Colonel Elrington, what was the last order that you gave to your subordinates?

Colonel Elrington: I ordered each company to pile up their weapons and wait for orders from the Japanese Army, and I gave the following message to everyone: “I am pleased that you have fought very well. We surrender not because of your mistakes, but because of orders. Remember your comrades who showed duty and discipline in death and defeat. Do not disgrace the honor of the Loyal Regiment even as prisoners of war.” Currently, we do not harbor any hostility towards Japan as soldiers.

Warrant Officer Moffat: All of us are grateful for our fair treatment by the Japanese Army.

【Censored by the Korean Military】

[Background Notes]

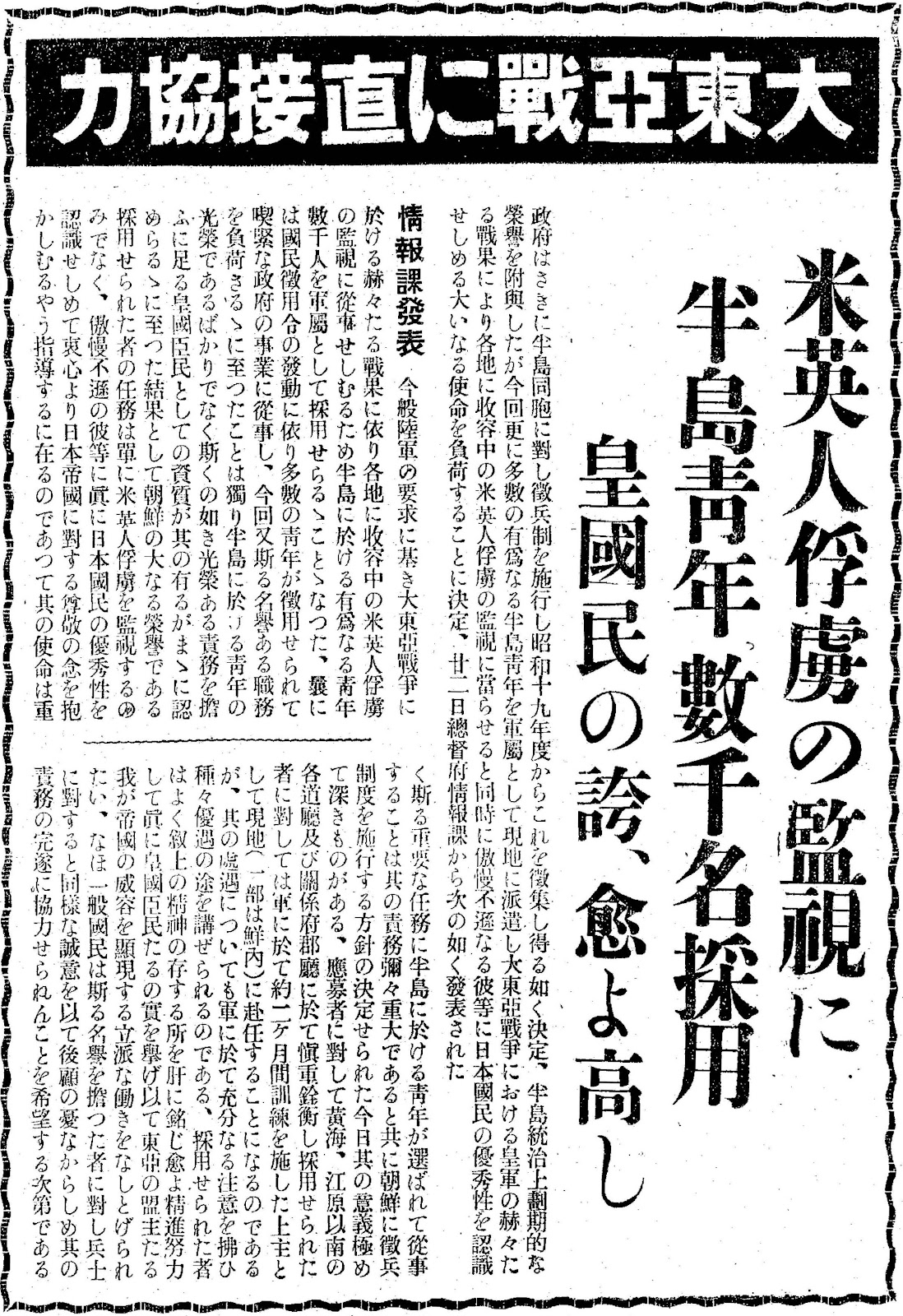

Prisoners of War served two functions for the Japanese: they provided slave labor, and they were exploited for propaganda. Prime Minister Tojo decreed that POWs would be located across Japanese territories to establish confidence in a Japanese victory amongst the local populations and to eradicate any lingering sense of western superiority amongst the people. A group of about 1000 POWs were sent to Korea for this purpose. But prisoners could serve another propaganda purpose, by providing accounts of Japanese military successes. As soon as the prisoners arrived in Korea, they were interviewed by reporters who wanted to hear all about their defeat in Malaya.

The account of the Malayan campaign and the Fall of Singapore in the newspaper article is based on a substratum of truth overlaid with Japanese inventions. The prisoners they interviewed were members of the 2nd Battalion, Loyal Regiment, who had been stationed at Singapore since 1938. In the interview, their senior officer, Colonel ‘Bill’ Elrington rightly admits that the northern defences on Singapore island were inadequate, and that the Japanese were more mobile than the forces under the command of Percival. Most of the British and Dominion troops lacked training in jungle warfare and were constantly outflanked by the Japanese, who made rapid progress down the Malayan peninsula. He also states, correctly, that the Japanese were able to establish air superiority from the early days of the fighting, and this was a significant contributory factor in the Japanese victory. Elrington’s men fought bravely and were indeed congratulated by their opponents immediately after the capitulation. But they suffered heavy losses: the total of 40% given by Elrington is possibly an under-estimate. The bayonet charges mentioned in the article are fictitious, although the Japanese troops did use bayonets in the last days of fighting, when they killed approximately 200 patients and staff in Alexandra Military hospital.

The interviewees would never had said that they felt ‘deep gratitude’ towards their captors: this is a trope of Japanese POW propaganda, nor would they have articulated the overly effusive praises for the Japanese soldiers that are attributed to them. Nevertheless, the reported words of the prisoners offer a real sense of the speaker’s personality: something of Captain Paque’s pugnacious and combative attitude towards his captors is seen when he tells the interviewers that the Loyals did not surrender of their own volition, but were ordered to, and were ready to fight to the death. What the article misses is that the men they interviewed all believed that the defeat was the result of poor leadership from the Commander-in-chief, Lieutenant General Percival and his senior staff. Later, it would be accepted that both the British armed forces and the British government had been complacent and wrongly assumed that they would be technologically and militarily superior to any Japanese fighting forces that dared to attack Singapore.

The prisoners were held at Keijo, a show camp, where visits by the Red Cross were manipulated to suggest that Japan was treating its captives fairly. Consequently, conditions in the camp were as good as in any Japanese POW camp. But the prisoners were regularly beaten, and lived on the verge of starvation. They suffered from diseases caused by malnutrition, the unhygienic living conditions and inadequate protection from the cold. At the time of the interview, Colonel Elrington was suffering from acute bronchitis which he had developed during the harsh Korean winter; his lungs never recovered. In 1945, the camp no longer served a useful propaganda purpose and Elrington was informed that, like the prisoners in the other camps in Korea, he and his men would all be executed in the event of a Russian or American invasion. Only the Japanese surrender prevented this.

The following is an excerpt from the diary of a fellow POW, A. V. Toze, which was at the Imperial War Museum in London:

February 12th 1943

Stan [Strange] together with Colonel E.[Elrington] and others were hailed to press conference ‘Office’ at 2pm and were interviewed by a host of reporters about fighting in Malaya.

They wanted to know why so many surrendered, were disappointed to learn that there were no bayonet fights, couldn’t understand ‘all’s fair in love and war’, the answer given to question ‘Did we consider the Japanese soldiers’ methods honourable?’

[Transcription]

京城日報 1943年2月15日

シンガポール崩るるの日

在鮮英俘虜にきく

優秀な皇軍の攻撃

正遇に心から感謝

大東亜の黎明。英国が東亜侵略の牙城として世界に誇ったシンガポールが陥落して一周年。大いなる歴史の日。昭和十七年二月十五日午後七時、わが山下将軍と敵将パーシバルと会見。”イェス”か”ノー”か断乎たる山下将軍の一声にパーシバルが震える手で無条件降伏に署名したのが同五十分ジャングルを突破し泥濘を踏み越え凄絶極まるシンガポール攻略戦はここに停戦したのだ。この日”祝シンガポール陥落”。

語る英軍俘虜:

- ローヤル聯隊第二大隊長:中佐エリントン(四五)

- 同第二中隊長少佐:ライトン(三三)

- 同第二大隊副官大尉:ペイク(三六)

- 同第三中隊附属准尉:モファット(三九)

- 迫撃砲中隊小隊長軍曹:ストレンジ(二九)

- ローヤル聯隊第二大隊第一中隊分隊長兵長:アンカース(三一)

問:マレー半島の防備には何時から就いたか?またシンガポールは何時までもちこたえると思っていたのか?

エリントン中佐:自分の大隊は一九三八年四月六日上海からシンガポールに移駐したのである。シンガポールは永久に持ちこたえると思っていた。

問:英軍は下士官でも小隊長になれるのか?

ストレンジ軍曹:普通は将校であるが、自分の隊はマレーに進んだ時、小隊長が負傷したので自分が代ったわけだ。

問:何処の戦闘で俘虜になったか?

ペイク大尉:自分達は捕らえられたのではない。パーシバル司令官から武器を捨てるようにいわれたのだ。

問:その時は何処に居たか?

ペイク大尉:アレキサンダー地区のギルマン兵営にいた。

問:日本軍との戦闘経過はどうか?

エリントン中佐:二月八九日に日本軍が東北と西北の二方面から攻撃してきたのであるが、自分達は日本軍から何処から攻撃してくるか判らなかった。戦前西海岸には防御設備はなかったのであり、此処で日本軍に対抗したのは豪州兵と印度兵であり、二日後にはブキテマ高地まで押されてしまったのである。自分達の聯隊は二月十日ブラクからブキテマへ行くよう命令され、わが大隊は十二日夜中までプキテマ附近で防備し待ちこたえていた。十二日になってから日本の兵隊がジャングルを突破し、自分の隊の後方に廻ってくるのを見受けた。これらの日本の兵隊は優秀な兵隊であった。

十三日、ボナビスターまで退却するように命令を受け、その夜アレキサンダーの街道へ後退した。この頃日本軍はブキテマ街道を戦車と歩兵で猛進撃し来った。十四、五の両日わが大隊は日本軍の砲兵と空中から攻撃を受けながらギルマン兵営を防御したのであるが、この戦闘が最も近接して戦ったものであった。

日本軍の猛烈なる攻撃には全く驚嘆した。白兵戦はライトン少佐(第二中隊)とモファット准尉(第三中隊附)とが十四日の夕方まで行ったのであるが、日本の兵隊は銃剣で突き込んでくるのに対し、わが隊は機関銃で対抗し、いくら撃っても日本の兵隊は小さな鬼のようにつぎからつぎと突き込んでくる。これには如何の精巧な機関銃でも駄目だった。日本の兵隊は人間ではないような気持ちがした。この激戦でわが第二、三中隊は僅か数名しか残さずやられてしまった。

自分達の大隊の左翼にマレー人の大隊が居た。これに日本軍が突入し左翼の海に近い方を日本軍が押さえたのである。仕方なく自分は大隊長として次の防備線はワシントン丘に新陣地を占めるよう命令した。これは十五日の午後二時から三時の間であった。夜八時パーシバル将軍から『全員降伏せよ』と命令がきた。翌日、日本軍の将校がきてローヤル聯隊は勇敢であったと讃えていた。

ペイク大尉:一月十四日、セーガーマットで日本軍と遭遇したのが最初であり、爆撃を受けたが戦闘ではなく退却した。この時対峙していた日本軍はゴム林とジャングルを見事に突破し海を通ってわが軍の後に廻ってきたのだ。

エリントン中佐:ムーアとホンベンの間に当るペーアンの戦闘には日本の戦車七台が現れ、歩兵が前進してきた。

ライトン少佐:普通の鉄条網と対戦車地雷で作った戦車障碍を日本の戦車が突破してきたが、交戦はなく、その日のうちに退却した。

モファット准尉:日本軍の行動は全く予想出来ず、後に廻ってくるので、いつも退却していた。日本軍は機動作戦が実に上手だ。

エリントン中佐:シンガポールに退却するまで四〇%の兵を失っていた。二十六日トラックでシンガポールに到着し補充隊として装備を整えていた。

モファット准尉:ジョホールを渡るときは日本軍の姿はまだ見えなかった。

問:シンガポール陥落の時の気持ちはどうだった?

エリントン中佐:降伏の命令を受けたときはビックリした。自分らはこんなことを予期してはいなかった。自分らは全力を尽くして戦ってきたが、命令を受けたから仕方がなかったのだ。

問:シンガポールに日本軍が上陸した報を聴いた時の気持ちは?

エリントン中佐:その時は予期していた。

ペイク大尉:自分達は全部殺されるまで戦う意志をもっていたが、命令を受けたから仕方がない。

問:シンガポール陥落の原因は何処にあると思うか?

エリントン中佐:北の方からの攻撃に対する設備は充分でなかった。シンガポールは南の海に面して防備していたのである。また空軍が非常に貧弱であった。降伏の直接の原因は”住民の死傷と街を壊さぬことことに日本軍が水道を占領していた”ことであり、これはパーシバル将軍の言でもある。

アンカース兵長:日本軍は数的にも優勢であり、空中からの爆撃が上手で自分等は陣地を守るだけだった。

ストレンジ軍曹:自分はギルマン兵営で戦闘中小銃弾が手先に当り負傷した。その時の記念に今でもその弾をもっている。

エリントン中佐:日本軍はジャングル突破などの機動作戦が上手で意表外な所から攻撃してくる。

問:では日本軍はジャングルを突き泥濘を冒し意外な所から攻撃するので非紳士的であるというのか?

エリントン中佐:いやいや、そうではない。自分らの軍隊では”戦争と恋愛とに於いては何をしても正しい”という標語である。日本軍攻撃は優秀である。

問:エリントン隊長が最後に部下に与えた訓示はどんなものか?

エリントン中佐:各中隊毎に武器を積み上げ日本軍の命令を待てと命令し、つぎのメッセージを全員に告げた:「自分は諸君が非常によく戦ったことを喜ぶ。諸君自身のあやまちではなく命令を受けたので降伏する。戦死に当り敗北に際しても義務と規律を示した諸君の戦友を記憶せよ。俘虜となってもローヤル聯隊の名誉を辱めるな」というのである。現在自分達は軍人として日本に対して敵意を持っていない。

モファット准尉:我々一同は日本軍の正遇に感謝している。

【朝鮮軍検閲済み】

Source: https://archive.org/details/kjnp-1943-02-15/mode/1up