How the war criminals of Imperial Japan shaped modern South Korean politics and business: the pro-Japanese legacy that Kishi, Sasakawa, and Kodama left behind in Korean conservatism

2024-12-10

198

2637

As a Japanese blogger posting content about Imperial Japan’s colonization of Korea, I have been following the latest news coming out of South Korea and noticed the dismay that many Korean citizens have about the “pro-Japanese” nature of their conservative politicians. By “pro-Japanese,” they refer to the way Korean conservative politicians are deferential toward Japanese politicians in matters of historical disputes, economic collaboration, and security agreements.

This deferential stance is often seen in the handling of contentious historical issues, such as the acknowledgment of wartime and colonial atrocities and abuses, reparations for victims of forced labor and sexual slavery, and the preservation of Japan’s national narrative over these events. Furthermore, it is reflected in agreements or compromises that seem to prioritize Japan’s strategic and diplomatic interests over addressing long-standing grievances held by South Korean citizens. These actions have often left a significant portion of the Korean populace feeling that their leaders are neglecting national dignity and justice in favor of maintaining close ties with Japan.

In this post, I’m going to tell a narrative to partly answer the question as to why these “pro-Japanese” tendencies persist in the Korean conservative movement in Korea, including some links with sources for further reading. This is by no means a comprehensive answer, but I hope this post becomes a resource to gather much of the relevant historical information about this issue in one place. In this narrative, I trace how Kishi Nobusuke organized former war criminals and other prominent former Imperial Japanese government and military officials to reconstitute as much of the former Imperial Japanese regime as possible in the post-war environment, then exert influence in Korea. Others have posted more detailed information online which explain how Kishi and his successors came to dominate the Liberal Democratic Party and Japanese politics, but in this post, I will focus more on the interactions that Kishi’s associates had with Korean government officials and businessmen over the decades to exert power and influence over South Korea in the postwar era. Through this exploration, I hope to provide readers with a deeper understanding of why these pro-Japanese tendencies persist in Korea and what it reveals about the ongoing impact of Imperial Japan’s colonial legacy in Korea.

We will begin this narrative in 1940’s defeated post-war Japan, ravaged by World War II and occupied by Allied forces. The Americans have imprisoned the class A war criminals at Sugamo Prison. However, other war criminals were released once the Americans decided that they could become useful anti-Communist leaders of postwar Japan. Among the released war criminals was Kishi Nobusuke, a key architect of Imperial Japan’s wartime economy. Kishi emerged from Sugamo Prison in the post-war years with a renewed ambition: to reconstitute as much of the old Imperial Japan as possible. He was emboldened by his observation that the Americans did not care what his true political beliefs were, as long as he was a staunch anti-Communist. Imprisoned as a suspected Class A war criminal, Kishi befriended two fellow war criminals who would become instrumental to his vision—Ryoichi Sasakawa and Yoshio Kodama. Together, these men cultivated a network that blended political influence, corporate ambition, and organized crime to reshape Japan’s role in East Asia.

In wartime Japan, Sasakawa was the founder and leader of the National Essence League (国粋同盟), one of the most extreme right-wing political organizations in Imperial Japan. Sasakawa admired Benito Mussolini and modeled his organization on Italian Fascist principles, even visiting Nazi Germany and fascist Italy in 1939. While he held a position as a Diet parliament member, Sasakawa spent much of the war giving motivational speeches to the Imperial Army and the general public across the Empire to boost war morale. In his remarks during one visit to Korea in 1943, he encouraged leaders to “punch Koreans with an iron fist” if they seemed unsteady and unfocused (ふらふら), claiming that such actions were acts of love (可愛ければこその鉄拳である) necessary to bring them back in line. This philosophy aligned with the broader Imperial Japanese military culture, which heavily relied on corporal punishment. In this way, he normalized the physical abuse of Koreans and rationalized it as an act of tough love to mold the Koreans into ‘true Japanese people’.

While incarcerated at Sugamo Prison, Sasakawa kept a detailed diary that highlighted his belief in aligning Japan with a pro-American, anti-communist stance. During his time at Sugamo Prison, he worked tirelessly to improve the treatment of prisoners, earning respect from both high-ranking war criminals and lower-tier detainees. Sasakawa famously referred to Sugamo Prison as his “ultimate university,” a place where he built relationships that later connected him to Japan’s post-war establishment.

Sasakawa later supported the controversial Unification Church founder Sun Myung Moon in his anti-communist activities. From 1968 to 1972, Sasakawa was the honorary president and patron of the Japanese branch of the International Federation for Victory over Communism (Kokusai Shōkyō Rengō), which forged intimate ties with Japan’s conservative politicians. Allen Tate Wood, a former top American political leader of the Unification Church of the United States, recalled his surprise upon hearing Sasakawa telling an audience, referring to himself, “I am Mr. Moon’s dog.”

Kodama, who was designated as the “fixer” by Kishi, utilized his connections to play a pivotal role in normalizing Japan-South Korea relations in 1965. Following the normalization treaty, Kodama frequently visited South Korea, where he liaised with members of Park Chung-hee’s administration, serving as a fixer for Japanese corporations and the yakuza. Kodama’s influence facilitated the inflow of $500 million in reparations and economic aid from Japan, which jump-started South Korea’s industrial development and created lucrative opportunities for Japanese businesses.

One of Kishi’s most significant collaborations was with Ryuzo Sejima, a former Imperial Army officer turned corporate strategist. Sejima, who survived 11 years as a Soviet prisoner of war, joined Kishi in forging the Japan-South Korea Cooperation Committee, which solidified ties between the two nations. This committee laid the groundwork for deep economic and political collaboration, with figures like Sejima serving as trusted intermediaries.

The normalization of relations between Japan and South Korea in 1965, made possible by a partnership between Kishi and South Korean dictator Park Chung-hee, was not merely a diplomatic milestone; it was a strategic alignment against the shared threat of communism. The reparations package and subsequent economic cooperation enabled Japanese firms to enter the Korean market, further intertwining the two countries’ fates. Park Chung-hee, a former officer in the Japanese-controlled Manchukuo Army, shared ideological and personal ties with Kishi and his associates. Park preferred to surround himself with fellow Imperial Army academy graduates, such as Paik Sun-yup, a decorated hero of the Korean War but a controversial figure due to his earlier service in the Gando Special Force of the Imperial Japanese Army in Manchuria from 1943 to 1945. Paik was also involved in putting down the Yeosu-Sunchon Rebellion (거수·순천 사건) of October 1948, a brutal operation marked by ransacking, raping, and killing of civilians, with many of the soldiers still wearing old Japanese army uniforms. This choice of associates reflected Park’s reliance on figures who, like himself, shared a connection to Japan’s colonial and military institutions.

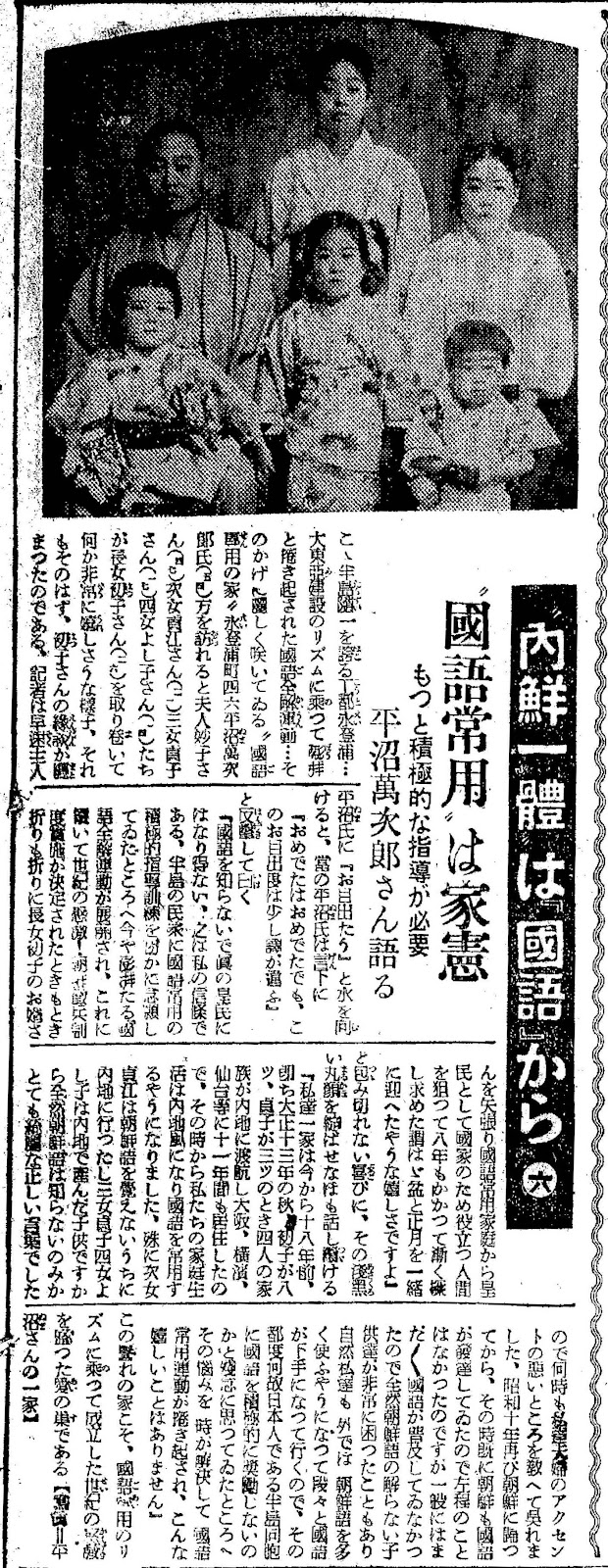

The predominance of pro-Japanese sentiments within South Korea’s conservative elite can be traced back to the early days of Syngman Rhee’s presidency. Rhee, whose domestic support base was weak, was forced to rely on collaborators with Imperial Japan to staff key positions in the police and military. The South Korean army, for instance, was largely founded and commanded by former officers of the Japanese military, while the police force was similarly dominated by those who had served under the colonial administration. This extended to other sectors as well, including the judiciary, media, education, culture, and religion. While Rhee himself cannot be described as pro-Japanese, the pillars of his government overlapped significantly with individuals who had thrived during Japan’s colonial rule.

The Special Committee for Prosecution of Anti-National Activities, established in October 1948 to address collaboration during the colonial period, was quickly dismantled after just over a year of activity. Although the committee compiled a list of approximately 7,000 alleged collaborators and arrested some prominent figures, its efforts were suppressed by the very police force that included former colonial officials. The committee’s offices were raided, effectively curbing its operations. [Source: Asahi Webronza Article]

The narrative of South Korea’s conservative elite shifted after independence. Their justification for maintaining power and influence centered on staunch anti-communism, pro-Americanism, and conservatism. Many former collaborators, once aligned with Japan, rapidly recast themselves as pro-American defenders of South Korea’s nascent democracy. In the context of a fierce Cold War rivalry with North Korea, this repositioning allowed them to frame their actions as vital for the survival of the state, rather than remnants of colonial oppression.

During the postwar period, Kishi and his allies cultivated relationships with South Korea’s emerging conservative elite, including Reverend Sun Myung Moon and business magnates such as Samsung’s Lee Byung-chul and POSCO’s Park Tae-joon. Lee Byung-chul’s business empire had its origins during the colonial era in Korea, with the establishment of Samsung Sanghoe in Daegu on March 1, 1938, initially focused on exporting dried fish and apples. His business success during this period likely would not have been possible without at least some collaboration with Imperial Japanese authorities. Samsung continues to exert significant political influence in conservative circles to this day. For example, The People’s Power party recruited Koh Dong-jin, an adviser to Samsung Electronics, ahead of the April 10 general elections in 2024.

Sejima played an instrumental role in shaping South Korea’s export-driven economy by advising on the establishment of trading companies and industrial giants. His insights were so valued that employees at Samsung Group organized book clubs around the Japanese novel Fumou Chitai (The Wasteland), whose protagonist was modeled after Sejima.

Another key contact for Kishi’s associates was Kim Jong-pil, head of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) and a close associate of Park Chung-hee. Kim’s support for the Unification Church, led by Reverend Moon, exemplified his efforts to consolidate a conservative, anti-communist bloc within South Korea. Notably, Kim, along with Park Chung-hee and Park Tae-joon, spoke Japanese so fluently that a Japanese diplomat once remarked that they seemed indistinguishable from native Japanese speakers. Additionally, Kim’s brother held secret discussions in Japan with Ichiro Kono, leading to an agreement to leave the contentious Takeshima/Dokdo issue unresolved, encapsulated by the phrase “settlement by not settling.”

Sejima’s deep connection with South Korea is evident in his memoir Many Mountains and Rivers (Ikuzanga), published in 1995. Sejima praised former President Park Chung-hee as “a self-disciplined leader with profound insight and leadership,” and expressed special respect for Lee Byung-chul, the founder of Samsung, calling him “a revered senior, brother, and teacher.” Through Lee Byung-chul, Sejima also forged ties with former Presidents Chun Doo-hwan and Roh Tae-woo.

Chun Doo-hwan and Roh Tae-woo, both military generals-turned-presidents who succeeded Park Chung-hee after his assassination in 1979, admired Sejima as a senior officer and respected his strategic insights. Chun Doo-hwan, in particular, felt that defending the Korean Peninsula from the North Korean threat was not solely South Korea’s burden but a shared responsibility with Japan. Chun argued that Japan, given its proximity and vested interests in regional stability, should actively contribute to South Korea’s defense capabilities. This stance led Chun to push for economic and military support from Japan, framing it as essential for the collective security of East Asia. These appeals resonated with Japanese leaders, who viewed a stable and anti-communist South Korea as a crucial buffer against Northern aggression.

A key episode highlighting Sejima’s close connections with South Korean leadership was his meeting with Kwon Ik-hyun, a prominent member of the Democratic Justice Party with strong ties to Samsung. In December 1982, acting as a special envoy for Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone, Sejima met Kwon Ik-hyun at Gimhae Airport for a secret meeting. The two reached a fundamental agreement to resolve the strained Japan-South Korea relations caused by issues such as Japan’s history textbook controversies and economic cooperation loans. This agreement paved the way for Yasuhiro Nakasone’s official visit to South Korea, aimed at resetting bilateral ties. Kwon, known for his strategic thinking and influence within South Korea’s conservative elite, worked closely with business magnates like Lee Byung-chul to align political and corporate interests. Through Kwon, Sejima was able to deepen his understanding of South Korea’s economic and political dynamics, further solidifying the partnership between Japanese and Korean elites.

Yasuhiro Nakasone‘s historic visit to Seoul in 1983 marked a new phase of Japan-South Korea cooperation. Behind the scenes, Sejima’s quiet diplomacy helped negotiate key economic loans that funded South Korea’s infrastructure, including the Seoul subway and power plants, while advancing Japan’s regional interests. This allowed Japan to influence South Korea’s political and economic trajectory in the 1980’s, culminating in events like the 1988 Seoul Olympics, which bolstered South Korea’s global standing.

The historical legacy of this network resurfaced in later years when Park Chung-hee’s daughter, Park Geun-hye, served as President of South Korea. In a poignant moment of historical significance, she met with Shinzo Abe, the grandson of Kishi Nobusuke, in 2015 during her presidency. This meeting resulted in an agreement intended to “finally and irreversibly” settle the contentious issue of comfort women. As part of the agreement, the Japanese government pledged $9 million to a fund for the surviving victims. For Japanese conservatives, this relatively small sum was seen as a way to put the darker aspects of Imperial Japan’s past to rest permanently, effectively allowing them to bury the history of wartime atrocities and abuses without further scrutiny. They viewed this as a significant political victory, expressing gratitude to South Korea’s conservative leadership for facilitating such a resolution. Indeed, Korean conservatives honored this agreement by refraining from criticizing Japan on the comfort women issue at a recent UN conference discussing women’s human rights issues.

This 2015 meeting between Park and Abe also symbolized the enduring influence of their respective family legacies in shaping Japan-South Korea relations. The interaction highlighted how the ideological and political frameworks established by Kishi and Park Chung-hee have continued to influence the bilateral dynamics between the two nations.

So what now? How is this relevant to the present? Many of the politicians and businessmen mentioned in this post have descendants and proteges who continue to carry on their legacy and dominate Korean conservative politics today. For instance, Paik Sun-yup’s daughter, Paik Nam-hee (백남희), recently established the Paik Sun-yup Memorial Foundation, describing it as “an organization of hope that consoles the hearts of the victims of the Korean War and their bereaved families.” This foundation portrays her father’s career in the most favorable light while omitting references to his controversial actions. Similarly, Samsung remains a family-run enterprise, with the founder Lee Byung-chul’s grandson now serving as its chairman, perpetuating the legacy of its founder.

The People’s Power Party of Korea today has strong incentives to safeguard the reputations of their predecessors, actively avoiding any revelations that might tarnish their image. This includes downplaying or suppressing colonial history, as such scrutiny could expose uncomfortable truths about Korean collaborators during the Imperial Japanese colonial period. As long as the collaborators and their descendants retain influence, a comprehensive and honest examination of Korea’s colonial and Cold War history may remain out of reach.

Ultimately, the neo-Imperialist ambitions of Kishi Nobusuke and his allies were not a direct attempt to restore Imperial Japan but rather to secure Japan’s position as a regional leader in the Cold War context. Through alliances with figures like Park Chung-hee, Chun Doo-hwan, and South Korea’s business elite, they leveraged historical ties and strategic interests to reshape East Asia. Today, their legacy remains deeply embedded in the political and economic structures of Japan-South Korea relations, for better or worse.