Imperial Japan waged an aggressive Japanese language campaign on Korean villages in the ’30s and ’40s, entering homes to attach Japanese labels on household objects, putting residents under 55 in mandatory classes, applying an “unyielding whip” to “break down their customs and stray dreams”

This article from Japan-occupied Korea in 1943 describes an aggressive Japanese language campaign that was conducted in Korean villages in the 1930s and 1940s, with one village, Guri-myeon, highlighted as a successful model for the rest of Korea. Today, Guri-myeon is now Guri-si and its adjacent Donggureung mausoleum appear to have been swallowed up by the urban sprawl of Seoul.

(my translation)

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) August 6, 1943

Patriotic peninsula in excitement over conscription

Japanese language engraved in all villages

The shining well-being of Guryong-myeon

The conscription system has been strictly enforced in the peninsula with glory and joy, and it has become an urgent issue that the whole peninsula must achieve excellent results in this brilliant system. The basis of this system is the need for the people of the peninsula to be rapidly transformed into true imperial subjects. As the first step in this process, understanding the Japanese language is of the utmost importance. The young men who will go to war as members of the Imperial Military in the next year are being trained with sweat and fervor in their hearts, but the peninsula in general must ceaselessly work hard not to be surpassed by these young men. All sides are now frantically rushing into a fierce campaign saying, “It is the Japanese language! All Korea should rise up to fully understand the Japanese language!” There is a beautiful patriotic village that is making a concerted effort to follow the example of this Japanese language movement.

If you go east from Seoul along the Gyeongchun Road for a while and pass Manguri Cemetery, you will come to Guri-myeon, Yangju-gun, a green farming village that has been cleaned of the dust of the city. This is the village that took the initiative early on in the campaign for the regular use of the Japanese language, pouring their shining efforts in preparation for the military draft. As soon as you step into the village, you will see the slogans and signs of the Japanese language campaign written in Japanese kanji, Japanese kana, and Hangul on signboards, gates of farmhouses, and pillars, such as “Start with the Japanese language for Japan and Korea to unify”.

It’s not just slogans and signs. If you take a step into a house in the village, you will find that everything is written with Japanese furigana, such as “wall,” “pillar,” “clock,” “hoe,” and so on, with explanations in Hangul, such as “this is a wall,” “this is a pillar,” “this is a clock,” and “this is a hoe”.

In this village, they call this teaching method the “Wall Reader” to promote the understanding of the Japanese language through hands-on education. However, it took a lot of careful planning and painstaking efforts to bring this complicated educational movement to fruition today.

Dongchang-ri, Guri-myeon, a model village, is located at the entrance to Donggureung, the site of the royal mausoleum of King Taejo of Joseon and his successors. Most of the villagers lived lives of idleness serving the mausoleum in the days before the annexation of Korea to Japan, and their customs lasted long after the annexation. As it was not easy to awaken into the new age when they were still dreaming of the idleness of the past, at one time they became a delinquent village outside of any administrative control due to the ineffectiveness of the government’s guidance, to the point where descended through idleness into a pit of poverty with the vicissitudes of time.

However, with the outbreak of the Manchurian Incident in 1931, the movement for the promotion of rural areas was vigorously stirred up in 1932, and the warm hands of the fervent spiritual mobilization movement were extended to these delinquent villages. The unyielding whip of welfare was applied to the stubborn villages, so that the villagers tended to wake up one by one from their dreams of idleness.

At this time, the events of the Second Sino-Japanese War strongly pulsed in our ears, and the leaders held many meetings, lectures, and round-table talks to inject the significance of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Holy War from all angles, and started a fierce movement for the imperialization of the country through school children. The current mayor of the ward, Mr. Yoshikazu Kido, took the lead giving beneficial guidance in this movement, and through his dedicated efforts, he succeeded in breaking down the customs and stray dreams of the village and reforming them. The Second Sino-Japanese War soon developed into the Greater East Asia War to defeat the United States and Britain. Upon seeing the results of the various battles, the villagers came to truly see themselves as imperial subjects. We have traversed many difficult paths to reach this point, considering that we expended an all out effort towards imperialization.

The core of the movement for the imperialization of Korea was the movement for the regular use of the Japanese language, but at first, the unawakened villagers made the myeon leaders and school principals suffer a great deal of hardship. Now, after four years of painstaking efforts, we have been rewarded with the results of this language training, and even the illiterate women of the village, who could not read a single character, are now able to understand Japanese katakana.

It is the pride of this model village that there is not a single man or woman from school-age children to 50-year-olds among the 16,000 people of Guri-myeon who does not understand the Japanese language.

The two men taking the lead are Mr. Aomatsu the myeon leader and Mr. Takayama the principal of Inchang Elementary School, and they have been working tirelessly to provide guidance. The painstaking work that these two leaders have put in can be traced back as follows.

Based on the firm belief that “without an understanding of the Japanese language, there can be no all-out national movement,” a leadership consultation conference was held among the leaders of the village offices, schools, police stations, financial associations, etc. As a result, the first thing they did was to set up academic training centers at five locations other than Inchang Elementary School. 1,200 children who have not graduated elementary school were housed in these academic training centers, and the young men of the village acted as instructors in embarking upon service education. On Wednesdays it was the turn of the boys group, and on Saturdays it was the turn of the girls group – both groups continued their earnest studies in two hour sessions. On the second Saturday of each month and on the 25th day of the month, a joint class was held at Inchang Elementary School, where the first year was spent learning vocabulary and the second year was spent learning conversational skills.

Not satisfied with merely teaching, officials have been actively encouraging and practicing the regular use of the Japanese language by doing things such as: 1. Attaching labels with the names of household items written in Japanese, 2. Placing Japanese slogans at required places, and 3. Having them agree to say simple words, such as greetings, all in Japanese. Officials gave teachers a monthly reward payment of 10 sen, and the village offices also gave priority distribution of kerosene to the language class sites, and designated the “Houses of the Japanese Language” as a model for the villagers to encourage them to continue their lofty endeavors. The process of Japanese language training continues to this day, and there is a night meeting for Japanese language training held in the community workshop of the village.

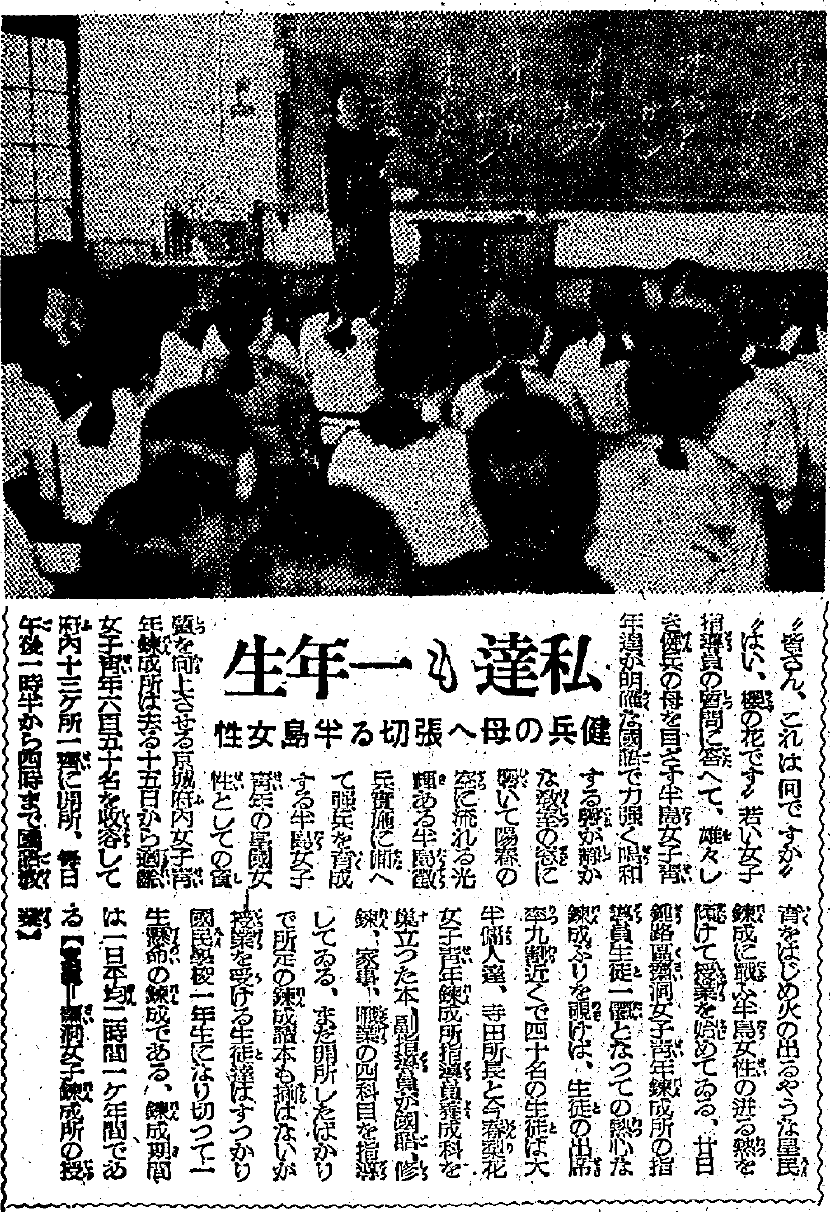

Those who gather there are divided into three groups according to their memory abilities: from 8 to 15 years old, from 16 to 20 years old, and from 31 to 55 years old. The young men in the village who are well versed in the Japanese language serve as teachers and give detailed guidance. Upperclassmen and graduates of the Elementary School always provide thorough instruction to women from ordinary households. In addition to holding occasional “speech presentations” at the workshop, efforts are being made to have the children of the Elementary School and the villagers use the Japanese language as much as possible, so that they can memorize and become familiar with as many words as possible.

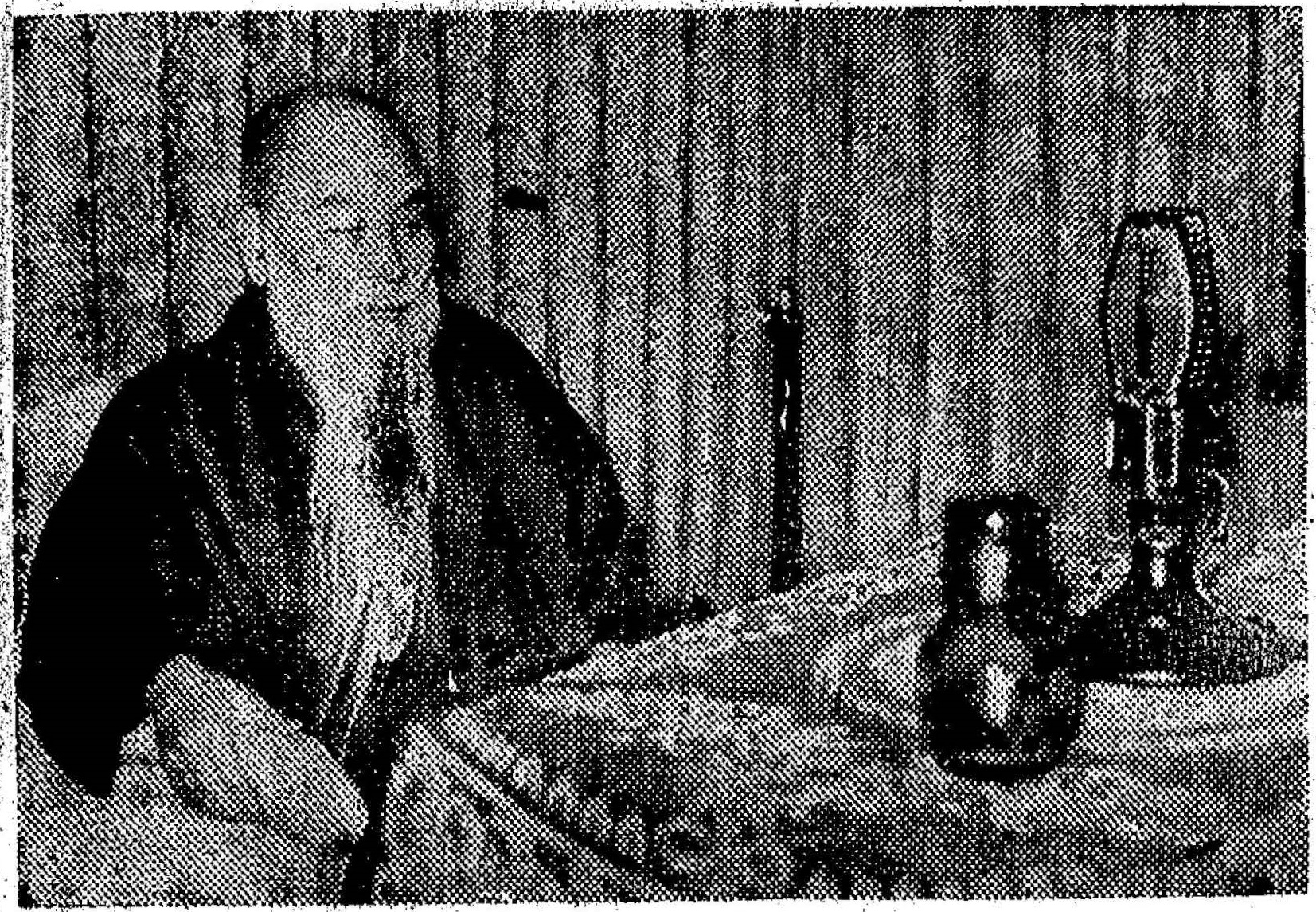

This campaign for the regular use of the Japanese language has led to the complete rehabilitation of the village. Today, the village is working together to develop an all out comprehensive campaign for all men between the ages of 14 and 60 and all unmarried women between the ages of 14 and 25. A national labor corps was formed, and it is yielding good results. Savings are also booming. Today, Guri-myeon is a beautiful, patriotic model village that is taking giant steps toward producing true imperial subjects, cooperating in crime prevention and building a village without a single criminal record in preparation for conscription, and making great strides in hygiene. Photo: Nighttime Japanese language class for women at the Elementary School.

(my transcription into modern Japanese orthography with punctuation marks modified and added for clarity)

Source: https://archive.org/details/kjnp-1943-08-06

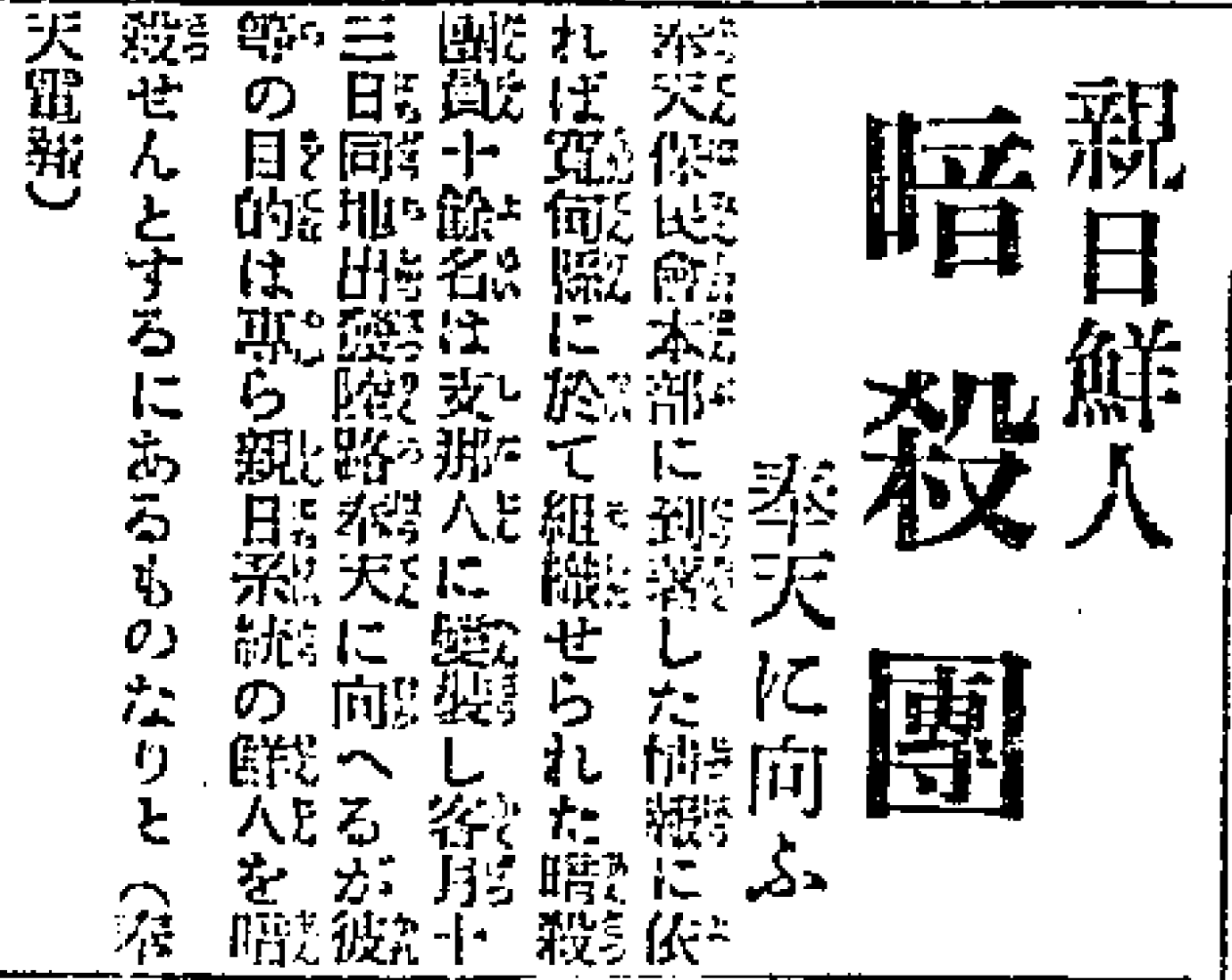

昭和十八年八月六日 京城日報

徴兵に沸る愛国半島

全村に刻む”国語”

九龍面の輝く厚生ぶり

徴兵制は栄光と歓喜のうちに半島に厳と布かれ、半島あげてこの輝く制度に見事なる成果をあげることが課せられた焦眉の問題となった。その根本をなすものは何を措いても速く真の皇民と純化されること。その実践の第一歩として国語の理解が何よりも緊要である。晴れて明年、皇軍の一員として戦争に起つ若人はいま汗と熱血の赤心を沸らせて錬成されているが、この若者達に断じて負けることなく半島一般も絶えず努力が払われなければならないーー国語だ、国語の全解に全鮮は挙れーーと各方面はいま必死となって猛運動に突入している。この国語常用運動に全部落挙って懸命な努力を払い垂範している麗しい愛国の村がある。

京城から東へ京春街道をしばらく行き、府の共同墓地忘優里を超えると都塵を洗い払った緑豊な農村楊州郡九里面がある。この村こそは晴れの徴兵制に備えて早くから国語常用運動に率先挺身して来た努力輝く村なのだ。この村に足を一歩踏み入れるや、立看板に、農家の大門に、柱に”内鮮一体まず国語”といった風な国語常用運動の標語、標識がそこにも、ここにも漢字と仮名と諺文とを併せて書き連ねてある。

標語や標識ばかりではない。一歩部落の民家を訪ねると、壁柱、時計、鍬など何から何まで振り仮名をつけ、それに諺文でこれが壁であり、柱、時計、鍬であると言った風な説明をつけている。

この村ではこれを”壁読本”と称して国語の理解を実物教育で推し進めているのである。しかし、この手数のこんだ困難な教育運動が今日よく結実するまでには精緻微密な計画と涙ぐましい努力が秘められている。

模範部落九里面東倉里はそのかみの李太祖以下代々の王陵のある地で東九陵の入口にあり、部落民のほとんどが陵に使え遊衣遊食の併合前の風習は、その後も長く続き、昔日の遊食を夢見ては容易に新時代に目覚めず、官の指導も一時は効果なく行政上全く手のつかぬ不良部落となり、遂には無為徒食から時代の嵐を喰って貧民窟にまで転落したのであった。

しかし満州事変の勃発とともに昭和七年農村振興運動が活発に捲き起こされ、この不良部落にも熱のこもった精神総動員運動の温かい触手が伸ばされ、頑迷の部落民に対して撓みない厚生の鞭が加えられ、部落民たちも何時か惰眠の夢から順次目覚めて来る傾向にあった。

この時支那事変は彼等の耳朶を強く搏って、指導者たちはまず支那事変と聖戦の意義を総ゆる角度から注入するために数多くの集会をなし、講話を続け、座談会を開き、学童たちを通じて皇民化への猛烈な運動の口火を切った。この善導の陣頭に起ったのが現区長の木戸義弼氏で、献身的努力はよく部落の因習と迷夢を打破し改革に成功したのであった。事変は直に米英撃滅の大東亜戦争に発展、緒戦の藹々の戦果に部落民は真に皇民として活眼し、皇民化一路にいま総力を挙げている思えば、幾多困難の道を踏み越え辿り来たのであった。

皇民化運動の中核をなしたものは国語常用運動であったが、覚醒せぬ部落民たちは最初は面長や校長さんたちを散々に手古摺らせたものだった。いまでは忍苦努力の四年に亘る国語講習成果は報いられ、一丁字もない文盲の部落婦人たちにも今では片仮名を解するまでに仕上げたのである。

九里面一万六千人のうち就学適齢児童から五十歳に至るまでの男女で国語を解しない者はまず一人も居ない…と言うのがこの模範部落の大きな誇りである。

いま陣頭にあって血みどろの指導に当っているのが青松面長と仁倉国民学校高山校長の二人であるが、この二人の指導者が注いで来た苦心の跡を辿るとこうだ。

”国語の理解なくして総力国民運動は駄目だー”との強く固い信条から部落の指導的地歩に起つ面事務所、学校、駐在所、金融組合等の首脳が鳩首協議の結果、まず仁倉国民学校の外五ヶ所に学術講習所を設け、未就学児童の千二百人を収容して部落の青年たちを指導者として奉仕的教育に乗り出した。一週間のうち水曜が男子組、土曜が女子組で二時間宛懸命になっての勉強を続けた。そして毎月第二土曜日と廿五日には仁倉国民校で聯合教授を行い、最初の一年は単語を覚えることで押し通し、第二年目から会話に移った。

教わるだけでは駄目だと班員たちは積極的に、各家庭の品物には名前を国語で記入した札を貼ること、◇所要の場所には国語常用の標語を掲げること。◇挨拶など簡単な言葉は総て国語で対話することを申し合せて、積極的に国語常用を励行実践して来た。班員は教師への謝礼として毎月十銭宛を持ち寄り、また面事務所でも国語講習会場には灯油の優先配給を行い、また激励のため『国語の家』を指定して面民たちの範とするなど尊い努力を続けて来たのである。いまも続けられる国語錬成の過程を見ると、部落の共同作業所内に国語の夜学会が開かれている。

ここに集って来る者は記憶能力に応じて八歳から十五歳迄、十六歳から廿歳迄、丗一歳から五十五歳迄と三組に分れ、部落の青年で国語に精通した者が講師として懇切な指導に当っているのである。また一般家庭の婦人に対しては国民学校の卒業生、上級在校生等が必ず一日一語の徹底した教授をする。時々作業場に集合して”話方発表会”を催すほか、国民学校の児童と部落民との話はなるべく国語を使用させて一語でも早く、一語でも多く記憶させ、しかも慣熟させるように努力を払っている。

こうした国語常用の運動は部落を全面的に更生させ、今日では共同作業、男子は十四歳以上六十歳未満、女子は満十四歳以上廿五歳未満の未婚者に対して総皆労運動を展開、勤労報国隊を編成して好成績をあげている。貯蓄も大いに振っている。衛生思想も今日では大いに挙り、防犯にも協力今日一人の前科者もない村に築きあげ徴兵制に備え、真の皇民への巨歩を踏み出している麗しき愛国模範部落なのである。【写真=国民校における婦人の夜間国語講習】