Imperial Japanese cartoon from 1943 shows how Koreans were forced to bow to the Emperor every morning, speak Japanese, and accept poverty without complaints

2025-02-14

136

717

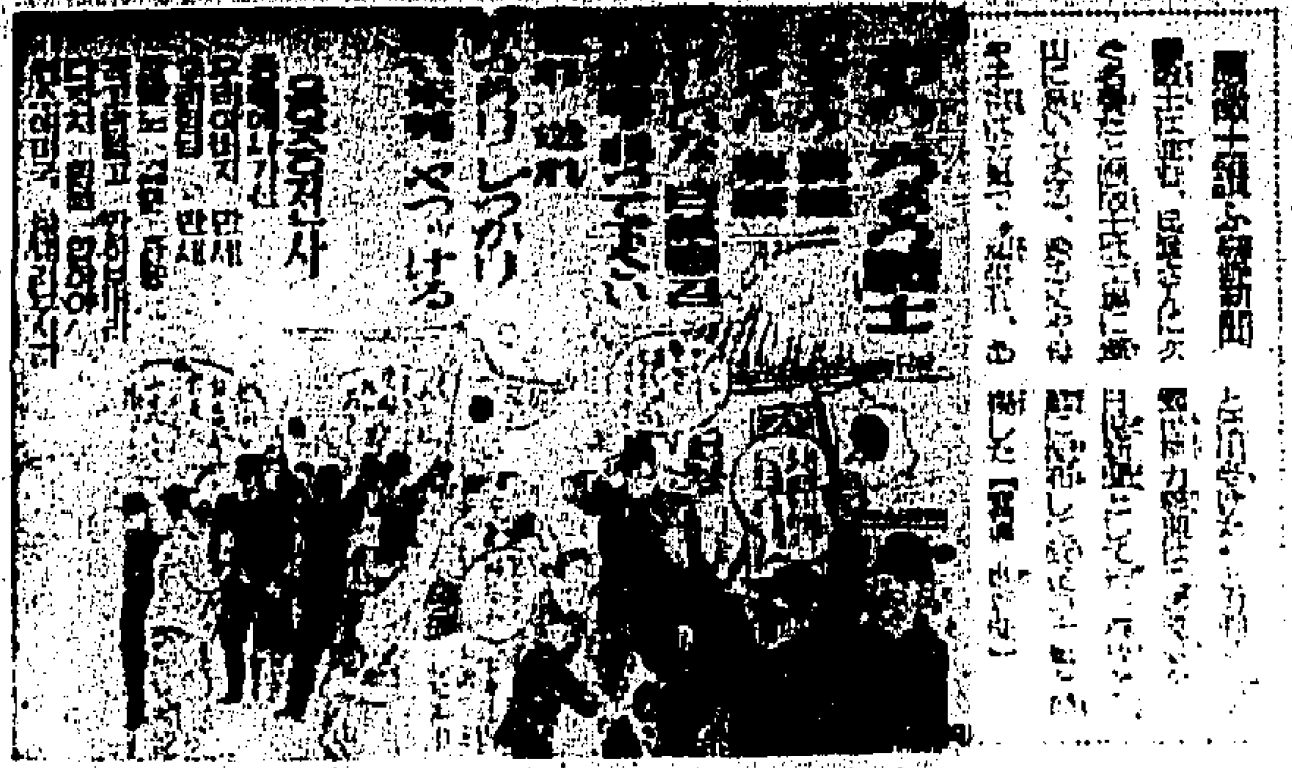

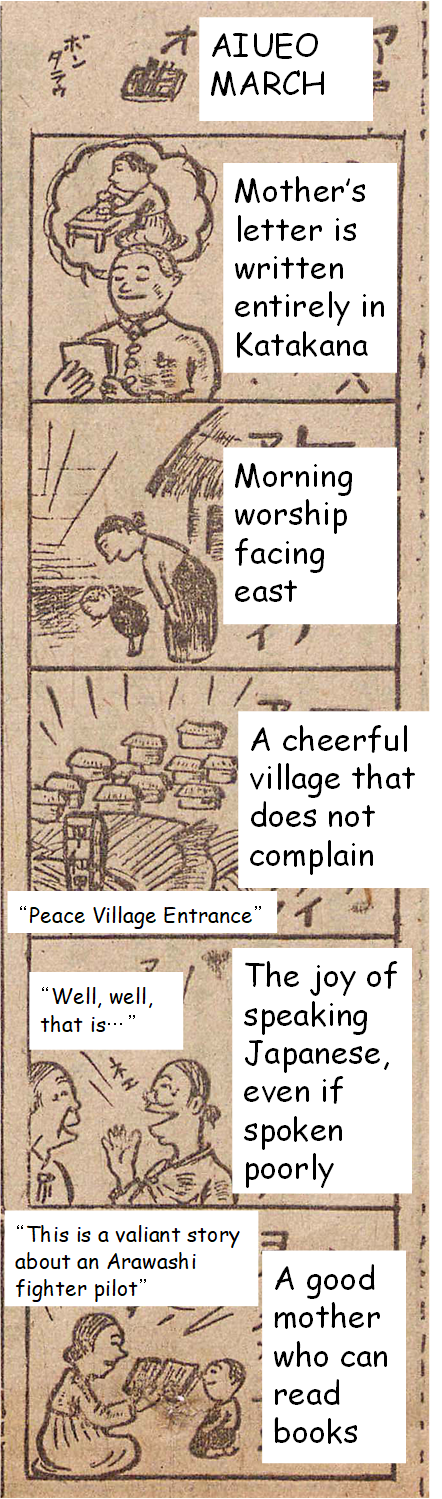

This 1943 propaganda cartoon depicts an idealized portrait of life as model Korean subjects under Imperial Japanese rule. It shows a soldier reading a letter from his mother written in Japanese in Katakana, mother and child making their daily mandatory morning bow towards the Imperial palace, a “cheerful village that does not complain”, two older Korean women speaking Japanese with joy, and a Korean mother sitting with her son reading a war propaganda story about a fighter pilot.

The translated text is as follows.

Frame 1: 母の手紙はカタカナばかり

Translation: “Mother’s letter is written entirely in Katakana.”

Context: The scene depicts a young soldier holding a letter and thinking of his mother. The fact that the letter is written only in Katakana suggests that his Korean mother is not fully literate in Japanese.

Frame 2: 東に向かって朝の遥拝

Translation: “Morning worship facing east.”

Context: This frame depicts Koreans performing 宮城遥拝 (Kyūjō Yōhai), the mandatory daily bowing towards the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. This ritual, imposed at 7 AM each morning with loud sirens, was meant to instill loyalty to the Japanese Emperor. It was part of the larger effort to erase Korean identity and enforce subjugation through cultural and religious indoctrination.

Frame 3: 不平を言わない明るい部落 (平和里入口)

Translation: “A cheerful village that does not complain.” (Peaceful Village Entrance)

Context: The “cheerful village” was often, in reality, a buraku—a shantytown where Koreans were often forced to live under poor conditions. By claiming that the village “does not complain,” the cartoon sends an overt message of compliance and submission, discouraging any dissatisfaction with their hardship. The name 平和里 (Peace Village) is deeply ironic, as these settlements were known for their substandard housing, lack of infrastructure, and poverty. The propaganda intent here is clear: to depict forced displacement as harmonious and orderly.

Frame 4: 下手でも国語で話す嬉しさ (あれあれ、あれがねえ~)

Translation: “The joy of speaking Japanese, even if spoken poorly.” (“Well, well, that is…”)

Context: This frame encourages Koreans to speak Japanese, reinforcing the Imperial policy of 国語常用 (Kokugo Jōyō), or mandatory use of the national language. Speaking Japanese was a requirement in schools, workplaces, and public life, with the use of Korean strongly discouraged or punished. The forced language shift was part of Japan’s broader assimilation campaign.

Frame 5: 本が読めて良いお母さん (荒鷲の勇ましいお話です)

Translation: “A good mother who can read books.” (“This is a valiant story about an Arawashi fighter pilot”)

Context: This frame glorifies military propaganda, depicting a mother sitting in front of her son and reading a story about 荒鷲 (Arawashi), or Wild Eagle, a reference to Imperial Japan’s fighter planes. The scene emphasizes the idealized role of a “good mother” as someone who educates her children with militaristic narratives, preparing the next generation to be loyal to Imperial Japan.

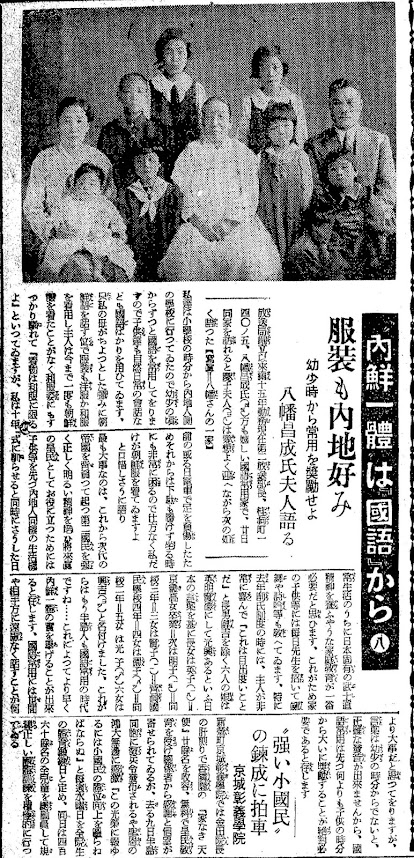

The アイウエオ行進曲 cartoon strip was part of a larger four-page supplement published in the November 18, 1943 issue of Maeil Sinbo (매일신보 / 每日申報), the last remaining Korean-language newspaper during the Imperial Japanese colonial period. By 1940, all other Korean-language publications had been shut down, and Maeil Sinbo, under strict Japanese control as a tool for Imperial propaganda, became the last operational Korean-language newspaper in Korea.

This supplement was written in basic Japanese, primarily using Hiragana and Katakana, to make it accessible to Koreans with limited Japanese literacy. But it was not just a language learning aid – it also doubled as a war propaganda medium.

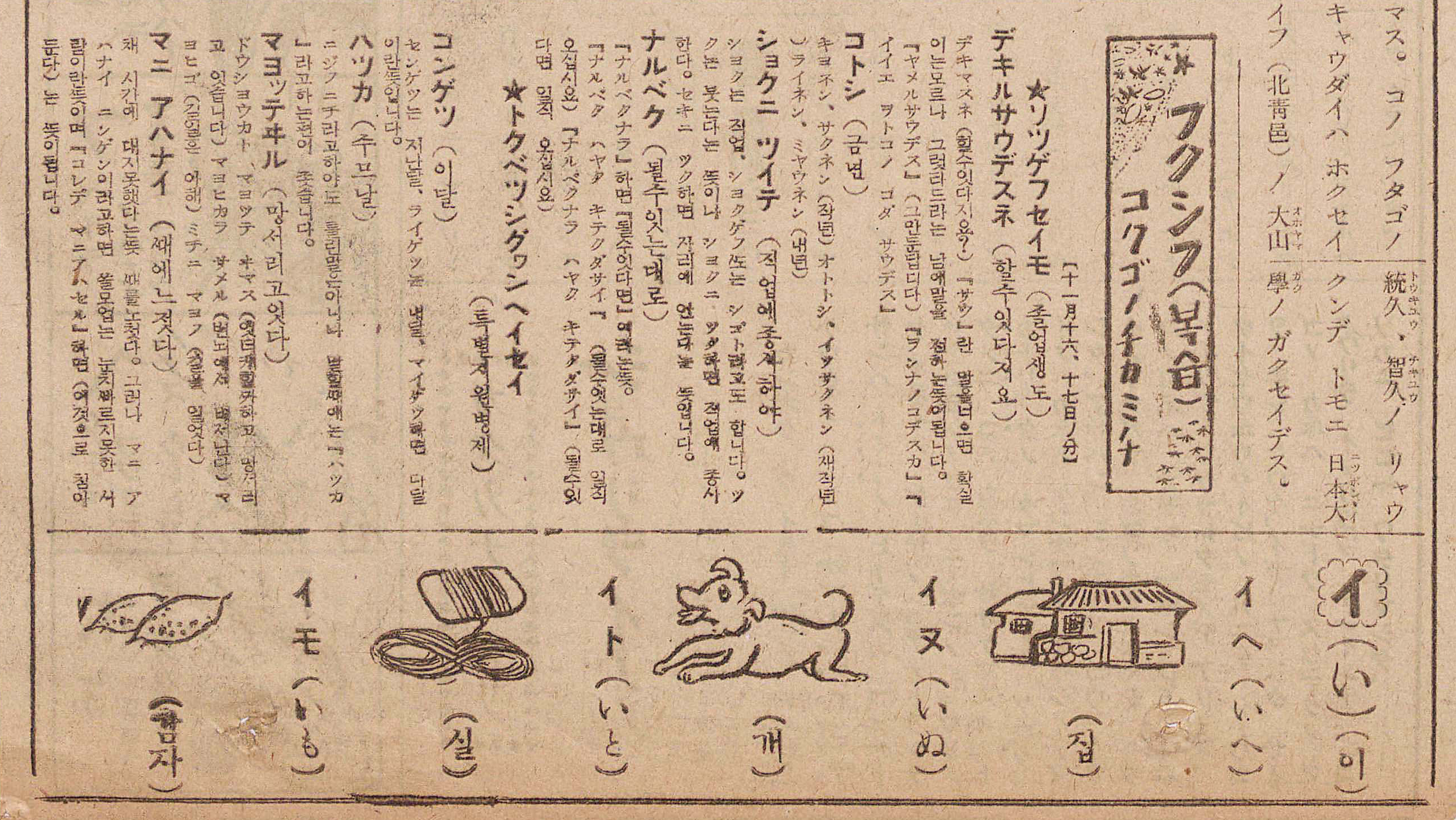

One of the most telling features of this supplement was its vocabulary column, which defined common Japanese words for Korean readers. This particular edition introduced words that started with い in Japanese, such as ‘house’ (家) and ‘dog’ (犬), making it appear like a simple educational tool. However, the section entitled「復習、国語の近道」(Review: The Shortcut to the Japanese language) reveals the true intent behind the supplement.

At first glance, this section provides simple definitions of Japanese words in Korean, such as:

- 今月 (kongetsu) – This month

- 二十日 (hatsuka) – The 20th day

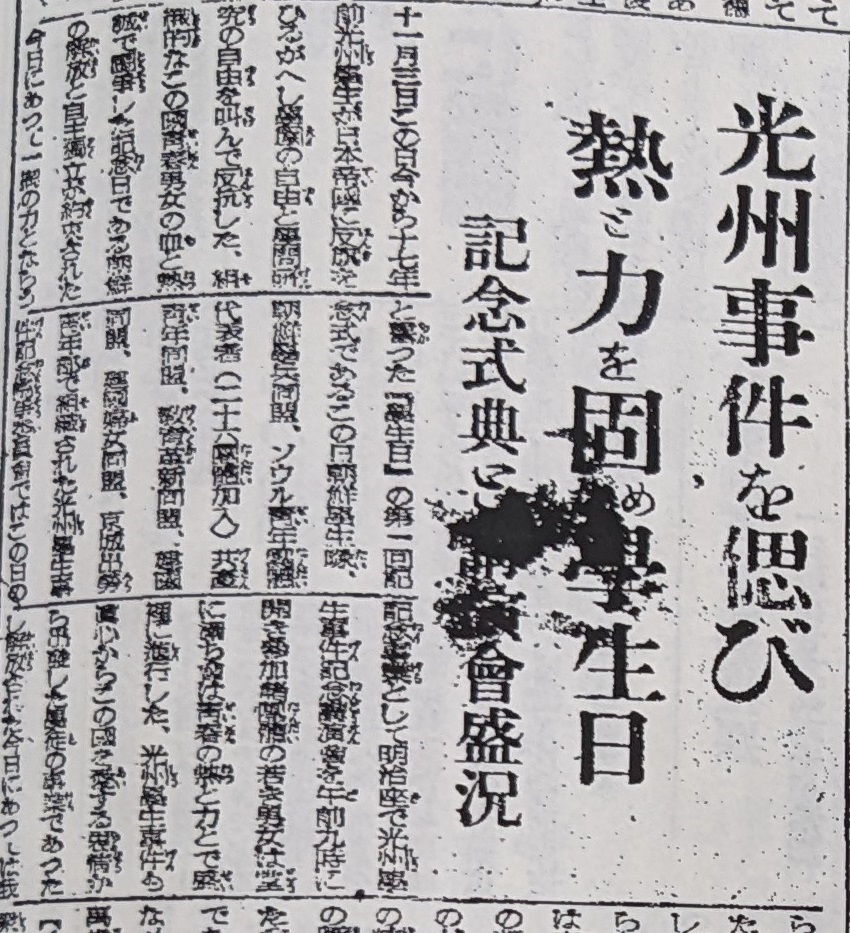

However, when these vocabulary words are strung together in context, they form a war propaganda sentence:

“卒業生もできるそうですね。今年職についてなるべく特別志願兵制。今月二十日迷ってる、間に合わない。”

(“It seems that even graduates can do it. This year, as much as possible, join the special volunteer soldier system. If you hesitate past the 20th of this month, it will be too late.”)

This sentence was a direct push for young Koreans to volunteer for the Imperial Japanese Army, reinforcing the recruitment drive for Korean soldiers under the 特別志願兵制度 (Special Volunteer Soldier System). This “voluntary” system was anything but voluntary—Koreans were heavily pressured, and by 1944, forced conscription was officially enacted.