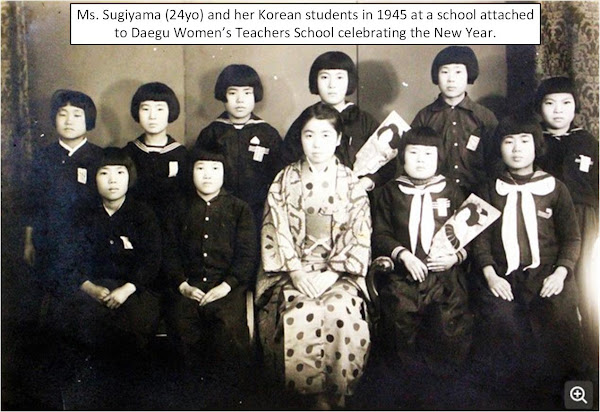

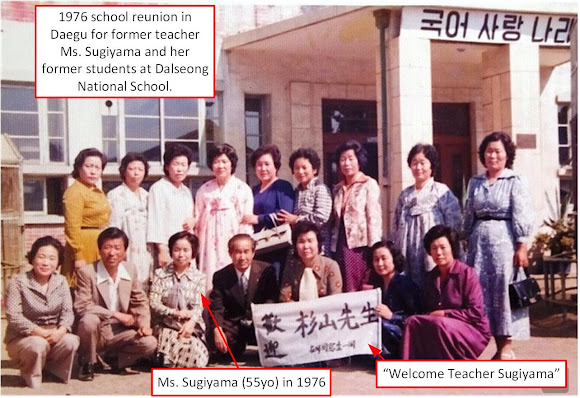

Japanese teacher in Japan-colonized Korea punished her Korean students for speaking Korean and imposed Imperial Way ideology on them during WWII; in 1976 at a school reunion in Daegu, she apologized and they forgave her; former teacher (now 100 years old) and students still keep in touch as of 2021

Blogger Note: Although the English version of this article is available here at the Asahi website, it is a very abbreviated version of the full Japanese language article, which has many more details of the full story, so I took it upon myself to translate the full Japanese language article below.

Article by reporter Nakano Arai, Asahi Shimbun, August 15, 2021

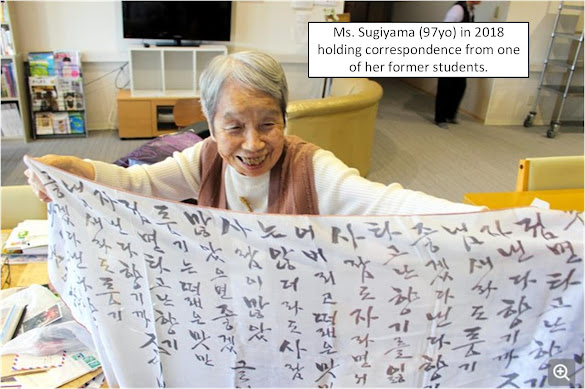

At an assisted senior residence in the suburbs of Toyama City overlooking the Tateyama Mountain Range, Tomi Sugiyama celebrated her 100th birthday in July.

In a box in her room is a bundle of letters from Korea. They were sent by former students of hers. ‘Teacher, are you feeling any pain in your body? I would like to meet you’. The letters are written in a mixture of Korean and Japanese.

’I consider Korea to be my homeland. My students are very compassionate’, she said as she narrowed her eyes.

Ms. Sugiyama taught at a national school (elementary school) in Korea, a colony ruled by Japan, for more than four years until the war’s end in August 1945. She taught wartime Imperialist education. She believed that it was the mission of teachers to turn Korean children into respectable Japanese people.

After the war, she was plagued by remorse for her involvement in war education, and her pain was eased through reunions with her students. Seventy-six years have passed since the end of the war, and as the number of people in the generation that experienced the war dwindles, Ms. Sugiyama’s life resonates today as a valuable historical testimony.

Ms. Sugiyama’s Birth and Early Childhood

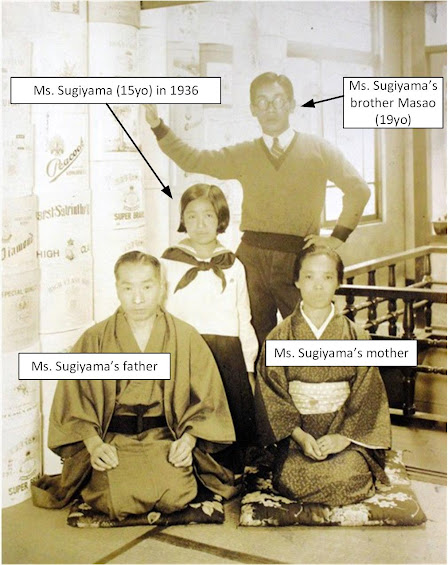

Her father, Genjirō, and mother, Sato, farmed the family’s fields in the former village of Sugihara in Toyama Prefecture. After Japan annexed the Korean Empire (the country’s name at that time), her father crossed the sea by himself to establish a foundation for his family in Korea. Her mother followed him carrying her older brother Masao, who was four years older than her.

Her parents settled in a farming village in Yeonggwang, Jeollanam-do (South Jeolla Province) in the southwestern part of the Korean Peninsula, where they ran a fruit orchard. Eventually, in 1921, Ms. Sugiyama was born.

She lived in Yeonggwang until she was about three years old. Her older brother was in elementary school, but it was too far away to walk from home to school. Her parents decided to move to the city for the sake of their children’s education and decided to give up the fruit orchard.

The peaceful rural landscape of her birthplace is faintly in Ms. Sugiyama’s mind, along with the white acacia flowers that bloom along the orchard road.

The family moved to Daegu, the capital city of Gyeongsangbuk-do province in the southeastern part of the Korean peninsula. Her parents set up a hat store at Motomachi 1-chōme in the center of the city. The name of the shop was changed to “Tomiya (富屋) Hat Shop” after the Chinese character 富 in Toyama Prefecture (富山), where the family was originally from.

Two young Korean men lived and worked in the store. Neither of the parents could speak Korean, so whenever Korean customers came to the store, the young Korean men would attend to them. They were called by their Japanese names, Wakichi and Ichirō.

Most of the store owners on the main street where their house and store were located were Japanese. Many of the Korean people were in the position of being used by the Japanese, and the Koreans lived clustered in areas slightly distanced from the main street. Ms. Sugiyama can only remember interacting with Japanese people among the childhood memories that she still has. She has no memory of playing with Korean children.

Not only in Daegu but also in other areas, Japanese immigrants in colonial Korea lived clustered together, forming Japan towns with rows of Japanese-style houses. Most of the schools that Japanese and Korean children attended were segregated, and Ms. Sugiyama’s classmates at the elementary school and high school for girls were also exclusively Japanese. In hindsight, this was a distorted feature of colonialism.

’When I was a child, I was taught at school that Japan and Korea came together because they became good friends. So, I didn’t feel the least bit guilty about it’, Ms. Sugiyama recalls.

One of the things she remembers most vividly from her days at the girls’ school was a school excursion to Japan proper. For Ms. Sugiyama, who was born and raised in Korea, Japan proper was ‘a place of yearning that made my heart numb’, she says.

Ms. Sugiyama in early adulthood

In 1905, Japan made the Korean Empire (the country’s name at the time) a protectorate and established the Office of the Resident-General of Korea (the first chief superintendent, Itō Hirobumi) after a war with Russia over its interests in Korea during the Meiji period (1868-1912). The government gradually increased its authority over Korea, including the deprivation of diplomatic rights and the dissolution of the armed forces, and in August of 1910, the Korean Empire became a colony of Imperial Japan under the Treaty of Annexation.

In 1938, Ms. Sugiyama was in the fifth and final year of school. In the midst of the Second Sino-Japanese War, they celebrated the Fall of Xuzhou by holding a flag parade during the day and a lantern parade at night, and the next morning they left in a hurry. From Busan, they crossed to Shimonoseki by ship and toured Kyoto, Nara, Kamakura, and other cities. Seeing Mount Fuji in the morning glow from the window of the train during the trip was an unforgettable memory.

In Korea at that time, students who graduated from girls’ schools were often trained as brides, and their mothers did not think that they should become professional women.

However, Ms. Sugiyama wanted to be independent. On the bulletin board of her school, she found an invitation to apply for a position at Seoul Women’s Teachers School. Although she was not an avid teacher, she decided to take the entrance examination. Her teacher persuaded her mother who was vehemently opposed to her becoming a teacher. It was a crossroads for her career as a teacher.

◇ ◇

Why did the reporter meet Ms. Sugiyama?

On August 15, 2016, Tomi Sugiyama’s article appeared in the special “Peace and War” section of the “Voices” section of the Asahi Shimbun (Osaka main newspaper edition) readers’ contribution column under the headline, ‘My Country was shattered in an instant’.

Nakano Akira, a reporter who has been covering the history of relations between Japan and the Korean Peninsula, including during his tenure in Seoul (2011-2014), has interviewed many Korean people who received Imperialist education under Japanese rule, as well as those who lived in colonial Korea and were repatriated to Japan after the war. However, he had no opportunity to meet anyone who taught in colonial Korea. He immediately visited Ms. Sugiyama to talk with her and was surprised to find that she continues to keep in touch with her students. He had this preconceived notion that Japanese who were involved in Imperialist education were resented after the war, but Ms. Sugiyama was different.

After visiting Ms. Sugiyama several times and exchanging letters and phone calls with her, he felt he understood a little more about why she was loved by her students.

After the defeat of Japan on August 15, 1945, the ‘illusion of colonialism’, in the words of Ms. Sugiyama, was shattered. Ms. Sugiyama, who believed that it was her duty to make the children of Korea into worthy Imperial subjects, began to look back at the past. When she met her students again about 30 years after the end of the war, Ms. Sugiyama expressed her regrets, and her students’ trust in her deepened.

As relations between Japan and South Korea continue to fray, Ms. Sugiyama’s footprints may provide a clue for rethinking our relationship with our neighboring country. With this in mind, we wanted to introduce Ms. Sugiyama’s life story this summer, when she turned 100 years old.

Ms. Sugiyama trains to become a teacher

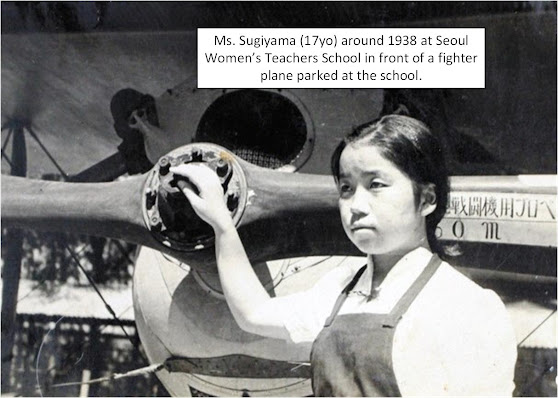

In 1939, the Second Sino-Japanese War had become a quagmire and World War II broke out in Europe. Tomi Sugiyama, who was born and raised in colonial Korea, graduated from Daegu Girls’ High School in the spring of that year and entered the training course at Seoul Women’s Teachers School.

She was 17 years old at the time. She was excited to live in a dormitory away from her parents, but she was not allowed to go out freely, and the rules were strictly enforced. The sound of a military-style bugle was the signal to get out of bed or to turn off the lights. Perhaps to heighten the war spirit, fighter planes were kept on the grounds.

Students came from all over Korea as well as from Japan proper. Unlike the girls’ school, where the classmates were exclusively Japanese, Japanese and Korean students studied side by side at their desks.

As a government-run school established by the Governor-General’s Office of colonial Korea, the educational content was thoroughly aimed at “Imperializing” the students.

In the school buildings and dormitories, the only language spoken was Japanese. The school’s motto, “We are blessed to be born in an Imperial country (Sumeramikuni)”, was the first thing that was drilled into their heads as they were taught the principles of being subjects of an Imperial country.

All lessons were about Japan. In Japanese, they studied Japanese classics such as Sei Shonagon. In music, the students were required to be able to play the organ to sing Kimigayo, the Japanese military anthem Umi Yukaba, and the four major festivals, including Kigensetsu, a national holiday in Japan.

There was also a mental training event called the “cold-resistance march”, in which the participants had to walk all day long to Incheon in the middle of winter in bitter cold so that their breath would freeze on their eyelashes.

The children of Korea were to be raised to be worthy Imperial subjects who would serve the Emperor. The role of the Teachers School was to train teachers who would lead the way in colonial education.

Ms. Sugiyama approached her daily classes with a sobering feeling. Although she did not originally aspire to be a teacher, as she studied diligently, her own “Imperialization” progressed like water soaking into a cotton wool.

However, her Korean friends may have felt differently. Later, an incident occurred that confirmed her thoughts.

A Korean friend was assigned a homework assignment to memorize the Imperial Rescript on Education, but she forgot about it. When asked by the teacher why, she replied,

’I didn’t want to memorize it.’

The teacher was furious and called her dormmate, Ms. Sugiyama, to question her friend’s attitude toward life.

Ms. Sugiyama replied, “I don’t think it was disrespect, nor was it ideological rebellion. I think she said in the worst possible terms that she had been negligent.” She desperately defended her Korean friend in this way.

Later, looking back, Ms. Sugiyama thought that her friend’s true feelings must have oozed out somehow. She was trying her best to show her defiance against Imperialist education.

It was an outward appearance of submission coupled with inward defiance. After defeat in the war, Ms. Sugiyama realized that the people of Korea, who seemed to outwardly accept Japanese rule, had a different attitude deep down inside.

The Imperial Rescript on Education, a gift from Emperor Meiji in 1890, taught Imperial subjects virtues such as filial piety and to come to the assistance of the Imperial family in times of crisis. It remained a fundamental principle of national morality and national education until the defeat of Imperial Japan in the Shōwa period (1926-1989). In 1948, after the war, the House of Representatives passed a resolution to eliminate the Imperial Rescript on Education, and the House of Councillors passed a resolution to confirm its revocation.

It may have been a time of war, but she also had some happy memories.

All students worked together to make kimchi to eat in the dormitories and pickled it in a jangdok fermentation pot. The welcome party for new students was a nighttime cherry blossom viewing event. It was the only nighttime outing allowed in strictly regulated school life.

They went on a school excursion to Manchuria (northeastern China). Manchukuo (Manchuria) was where the Imperial Japanese military was stationed and the economy was controlled by Japanese state-sponsored companies such as the South Manchurian Railway. As the international community pointed out, it was under Japanese influence as a puppet state, and travel from Korea by rail was possible.

Ms. Sugiyama starts working as an elementary school teacher

In the spring of 1941, Ms. Sugiyama graduated from the Teachers School. Her mother, who had opposed her going on to higher education before she enrolled in the school, rushed to the graduation ceremony herself.

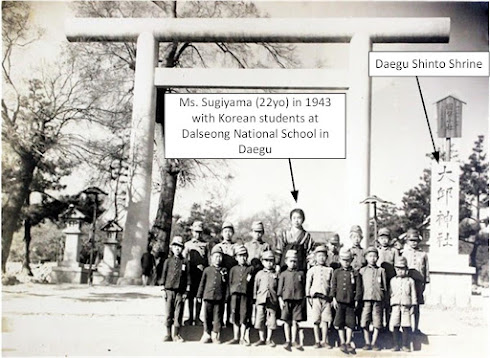

She was assigned as a new teacher at Dalseong Public National School (elementary school), a school for Korean children in her hometown of Daegu. As the wartime atmosphere deepened, elementary schools and other primary educational institutions were renamed “National Schools” from that year.

Ms. Sugiyama, who was only 20 years old at the time, was full of energy and a sense of responsibility.

”I will raise the Korean children to be respectable Japanese people and respectable Imperial subjects.” She believed that this was the duty of a teacher, and she stood up to teach.

In the spring of 1941, at the beginning of the Pacific War, Tomi Sugiyama taught for the first time in Daegu, colonial Korea. She taught fourth graders at Dalseong National School for Korean children.

The use of Korean was absolutely prohibited. The students were required to repeat the “Kyūjō Yōhai ritual” (bowing in the direction of the Imperial Palace) and bowing to the Hō-an-den shrine, which held the Imperial image of the Emperor and Empress and a copy of the Imperial Rescript on Education. They were also required to recite the Imperial Japanese vow (皇国臣民ノ誓詞) every day, saying such phrases as, “We will unite our hearts in loyalty to His Majesty the Emperor”.

In her second year, she became the homeroom teacher for the first grade. On the day of the entrance ceremony, Ms. Sugiyama sewed a nameplate on the chest of each new student’s uniform with his or her Japanese name, which had been changed in accordance with the Sōshi-kaimei policy of pressuring Koreans to adopt Japanese names.

The name change was implemented in 1940 after the Governor-General of Korea revised the Korean Civil Code in 1939 as part of the Imperialization policy. It asked people to change their names from Korean family names to Japanese-style names. The people of Korea, who traditionally valued their ancestors, were told through their workplaces and schools that they would be disadvantaged if they did not comply.

They had classes in the exercise yard outside under blue skies. When Ms. Sugiyama called out, “Sit down,” the children imitated her by saying, “Sit down,” in unison. The first graders did not yet understand Japanese, so she had to help them learn Japanese as soon as possible, she strongly thought.

Now, looking back, Ms. Sugiyama imagines how frustrating it must have been for the children. They were called by their unfamiliar Japanese names, and most of all, it must have been difficult for them not to be allowed to speak their own language.

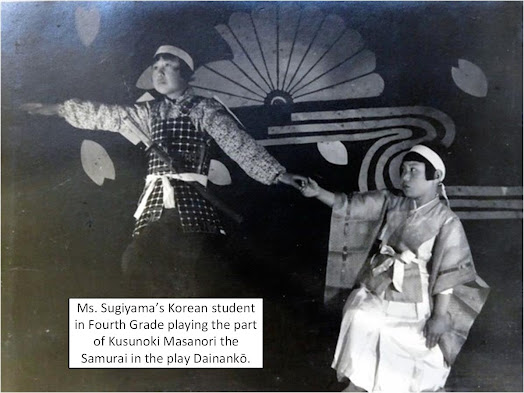

School events took on a warlike atmosphere. At the school arts and crafts festival, the children were asked to perform the play “Dainankō,” in which Kusunoki Masanori, a military commander who was revered for having dedicated his life to Emperor Go-daigo, played the leading role. The children were also asked to make picture scrolls to be placed in comfort packages sent to soldiers in war zones. The children were also made to pick up pine needles and catch tanishi (Japanese mysterysnails) for “national defense contributions” to be given to the military.

There were also Korean teachers at the National School, but they were treated differently from the Japanese teachers, with only the Japanese teachers receiving additional benefits. Ms. Sugiyama, a newly appointed teacher, was paid more than her more senior Korean colleagues, who had families of their own.

The staff morning assembly was held in front of the kamidana Shinto altar in the principal’s office, and everyone recited a poem said to have been composed by Kusunoki Masanori to express his loyalty to Emperor Go-daigo, to strengthen their minds and bodies.

As wartime controls tightened, a shocking event occurred

Japanese military police suddenly arrived at the school and took away two young male Korean teachers. No explanation was given to the other teachers, and the two never returned to the school.

The Japanese military police (Kenpeitai) were keeping a close eye on the independence movement resisting Japanese rule. Were the Korean teachers harboring hidden feelings that they did not reveal to the Japanese teachers, even as they were carrying out the “education for Imperialization” that sought to erase the Korean language and culture?

After the liberation of Korea following Japan’s defeat in World War II, Ms. Sugiyama saw one of these Korean teachers wearing an armband that read “Independence Preparatory Committee”.

Among the experiences in their school lives which aimed to turn the Korean students into respectable Imperial subjects, there was one lesson that made a long-lasting impression in the minds of her students.

There was a sewing class for 4th grade girls. The way to carry a needle and apply a jointed cloth differed between Japanese sewing techniques and Korean sewing techniques, but the teachers were required to teach the basics of Japanese sewing techniques.

One day, the children asked to be taught how to sew beoseon, which are a type of Korean socks shaped like boots with pointed toes. Realizing that sewing techniques rooted in daily life would be more useful for the children, Ms. Sugiyama asked her mother, who was fluent in Japanese, to come to the school and teach the class with her.

”It was a secret, unconventional class. If the principal had found out, I would have been summoned to the school and given a big scolding or at least forced to write an apology”, Ms. Sugiyama said.

She had completely forgotten that she had taught such a class.

More than 30 years after the war, she met again with some of her students in Korea, and as they reminisced, one of them said, “Ms. Sugiyama, I sewed beoseon at school. We remember it well”.

It brought back memories of her younger days at the National School, when she was trying to respond to the wishes of the children.

The Imperial Japanese style of education was an attempt to instill the Japanese way of doing everything into the children’s consciousness, including their language, their names, and their lifestyles. At the time, she believed that it was her responsibility as a teacher to carry out this style of education, so she devoted herself to her daily lessons.

Looking back, however, she realized that she may have been harboring a little bit of doubt in her heart about this style of education. She was relieved to come to this realization about herself.

Ms. Sugiyama loses her older brother in the Pacific War

It was a painful event, and her memory of when it happened has faded.

Late in the Pacific War, Tomi Sugiyama, who was living in Daegu in colonial Korea, received a notice informing her that her brother who was four years older than her had been killed in action in a war zone to the south.

No specific information was given as to where or why her brother died, and neither his remains nor his belongings were ever delivered. Her brother left for war shortly after his marriage. He did not know that his new wife had given birth to twin daughters, and his dream of taking over his father’s hat store was cut short.

In January 1945, Ms. Sugiyama was transferred from Dalseong National School, where she had taught for nearly four years, to the National School attached to Daegu Teachers School.

Japan proper was bombed indiscriminately by the U.S. military, and many civilians were killed. Although Korea was never hit by a full-scale air raid, the students at the school repeatedly practiced evacuating to air-raid shelters and defending themselves from machine gun fire on a daily basis.

National Liberation Day of Korea – August 15, 1945

Schools were on summer vacation. At noon, there was an announcement that an important broadcast was to be made, and although she sat in front of the radio to listen, she couldn’t understand it very well. Her father, who listened with her, was silent. Toward the evening, the whole town began to cheer and make a commotion.

”Doknip manse! 독립 만세! Long live independence!”

She learned of Japan’s defeat in the war. For the Korean people, it meant liberation from 35 years of Japanese rule.

”I never thought that Japan would lose the war, and I never expected at all that Korea would gain independence if Japan lost”, she said.

Looking back, Ms. Sugiyama had planned to continue working as a teacher in Korea, where she was born and raised. She was sure that many other Japanese living in Korea thought the same way. However, the “illusion of colonialism” was shattered in an instant.

Early in the morning of August 16, Ms. Sugiyama set out for the outskirts of Daegu. She was going to pick up her mother, the widow of her brother who had been killed in the war, and her twin nieces, who had been evacuated to a farming village.

While standing in line at the bus terminal, a young Korean man suddenly approached her.

He said, “Young lady, you are Japanese, aren’t you? This is not Japan anymore, so Japanese people should get off”.

With that, he stepped in front of her and pushed her out of the line leading to the bus. She was shocked and speechless. She gave up boarding and began to walk alone.

After a while, she heard a voice calling out, “Teacher!” It was a boy named Yoshikane Seishō (real name Kim Jong-seop 김정섭/金正燮), one of the 4th grade students whom she taught when she first started teaching at Dalseong National School. He gave her a ride on his bicycle as he guided her to her destination.

As they were riding along a rural road, a large number of people were walking toward the town. As she was talking with Kim, wondering what kind of people they were, she was suddenly shouted at in Korean by someone she passed by.

”What did he just say?” she asked. “It’s better not to ask”, the boy replied. When she asked him again and again, Kim finally answered, “He said, ‘Don’t speak Japanese. Speak Korean'”.

Ms. Sugiyama couldn’t help but raise her voice on the spot.

”What’s wrong with speaking Japanese?”

She became calm, and then she had a revelation. She herself had been the one who had ordered the Korean children to speak Japanese, not Korean, on a daily basis. She was shocked to realize this.

At the time of the war’s end, it is estimated that there were over 700,000 ethnic Japanese people in Korea, but repatriation from the north of 38 degrees north latitude, which was occupied by the Soviet Union, was extremely difficult, and many died of hunger and cold. The authorities did not allow the engineers to return home, and many of them, including Japanese women who were married to Korean men, remained behind.

She joined her family and returned to the hat store in Daegu. The young Korean men who had been living and working there disappeared, so they stayed inside their home while leaving the store closed.

Soon after, the school where she used to work gave the order for the staff to assemble. They dug a large hole in a corner of the playground, carried in documents, books, and kamidana Shinto altars, and set them on fire. The traces of Imperialist education were reduced to ashes.

Ms. Sugiyama stood in a daze in front of the rising red flames. What was the meaning of all those days that she had lived through up to the present day?

Believing that it was her mission to raise the children of Korea to become worthy Imperial subjects, she had devoted her days to education. Everything she had built up until then instantly crumbled away, and she felt a gaping hole in her heart.

Ms. Sugiyama moves to Japan

As the ship left the port of Busan, her days in Korea, where she was born and raised, came to mind.

In the fall of 1945, Tomi Sugiyama left Korea, where she had lived for over 24 years, on a repatriation ship.

She took a train from Fukuoka to Toyama, her parents’ hometown, and moved in with relatives in the former village of Sugihara. She worked hard at farm work, which she was not accustomed to, and she also worked as a walking salesperson.

She felt guilty for having been on the front lines of Imperialist education and having cooperated in the war effort, and she felt sorry for her students in Korea. She vowed to herself that she would never take up teaching again.

However, amid the postwar shortage of teachers, she was encouraged many times to return to teaching. In 1947, persuaded that there were many children in need, she took over a teaching position at an elementary school after a teacher took a leave of absence due to childbirth. The content of the teaching curriculum had changed.

Meanwhile, the Korean Peninsula continued to undergo a period of upheaval. After Korea was liberated, U.S. forces occupied the south side of the 38th parallel, while Soviet forces occupied the north side. In 1948, South Korea and North Korea were founded one after the other, dividing the country into north and south.

In Toyama, the Sugiyama family received a letter from Kim Jong-Seop hoping for a reunion with his former teacher. He was the former student at Dalseong National School in Daegu who had helped the family until they were repatriated. However, they lost contact after the outbreak of the Korean War (1950-1953).

Ms. Sugihara meets her former students again

In 1972, when the Sapporo Winter Olympics were held, she unexpectedly learned of Kim Jong-seop’s whereabouts. He was now the South Korean consul general stationed in Sapporo. His wife was Kim Sam-hwa (김삼화/金三花), another former student of Ms. Sugiyama who adored her. After the Olympics, they met again for the first time in 27 years, and the three of them sang “Spring Stream (haru no ogawa)” and “Arirang” together.

In 1976, Ms. Sugiyama was invited by Kim Jong-seop and his wife Kim Sam-hwa, who had returned to their home country, to visit her birth country the first time in 31 years. At Gimpo Airport in Seoul, she was greeted by her former students as well as former classmates at the Teachers School.

She also headed to Daegu, where she had taught for more than four years. When the bus arrived, women in traditional dress ran up to her and said, “Teacher!” They held each other’s hands.

At the welcome banquet, Ms. Sugiyama reflected on the past and apologized for trying to force everyone to become Japanese people through Imperialist education. She had always been plagued by remorse and could not help but speak out. Her former students just listened quietly.

Some of her former students refused to attend the welcome banquet, perhaps out of distrust of Japan and Japanese people. But once they were told that their former teacher had apologized, they showed up on her subsequent visits to Korea.

There was one former student, Park So-deuk (박소득/朴小得), who remained a source of concern. She was a fourth-year student at Dalseong National School. After graduation, she was encouraged by her teachers at the time to join the “women’s labor volunteer corps” so that she could study while working, and she was mobilized to work at a military factory in Toyama.

Ms. Sugiyama told her students that her parents were from Toyama. This student lingered in her heart because she had raised her hand when this familiar geographic name was mentioned, but she had no idea what happened to her after the war.

In 1993, Park So-deuk came to Japan as one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed by former “labor volunteer corps” members seeking compensation from the Japanese government. Hearing that Park So-deuk wanted to meet her, Ms. Sugiyama rushed to a supporters’ rally in Fukuoka and greeted her.

”I am sincerely sorry for having suppressed the language of your country and imposed war-mongering education on you,” she said. “I feel like my chest is about to burst open, when I see you continuing to adore me despite everything I did to you”.

She could not study at all during her time in the “labor volunteer corps”, like she was promised. At the very least, she wanted the Japanese government to pay her back wages. The Japanese government and companies did not respond to the lawsuits of Park and other plaintiffs, and the Japanese judiciary also did not respond.

Park So-deuk passed away, her resentments still unresolved. Ms. Sugiyama’s regret of not being able to help her student will never go away. (Blogger note: Park So-deuk worked at the Nachi-Fujikoshi munitions factory in Toyama during the war. Although she personally could not receive compensation from the Japanese government, other ex-laborers who also worked at the same factory received a favorable ruling from the Seoul High Court ordering the Japanese machinery manufacturer to pay up to 100 million won each to 33 women who say they were forced to work for the company during the war.)

Japan and South Korea concluded a claims agreement when diplomatic relations were normalized in 1965. The Japanese government maintains that the agreement “completely and finally resolved” the issue. On the other hand, in 2018, the Supreme Court of the Republic of Korea recognized the claims of individuals, including former laborers, and ordered Japanese companies to compensate them, which has become a diplomatic issue.

One of Ms. Sugiyama’s students has won prizes for his novels in Korea. He told Ms. Sugiyama that he decided to become a writer after his picture diary was praised by Ms. Sugiyama. Ms. Sugiyama herself had forgotten about it. She realized the weight of a teacher’s words.

After the war, Ms. Sugiyama worked as an elementary school teacher in Toyama for about 27 years. After retiring, she participated in a Japan-Korea exchange program organized by a private organization in Toyama prefecture and visited Korea many times. She has a favorite saying in the Korean language, which she began to learn after she had reached the age of 60.

“If the words that go out are beautiful, the words that come back are also beautiful” – “가는 말이 고와야 오는 말이 곱다”

If we exchange words that show consideration for one another, then the tensions in the relationship between Korea and Japan will surely be relaxed.

This was Ms. Sugiyama’ message.

Reporting by Nakano Akira (中野晃) of Asahi Shimbun Newspaper

Translated by blogger from: https://www.asahi.com/rensai/list.html?id=1298&iref=pc_rensai_article_breadcrumb_1298

(Original Japanese text)

あの海の向こうに ~植民地で教えた先生~①(全5回)

立山連峰をのぞむ富山市郊外のサービス付き高齢者向け住宅。ここで暮らす杉山とみさんは7月で満100歳の誕生日を迎えた。

自室の箱には、韓国から届いた手紙の束が詰まっている。かつての教え子から届いたものだ。「先生、体に痛いところはないですか。お会いしたいです」。韓国語と日本語が交じった文面でつづられている。

「韓国は私にとっては、ふるさと。教え子たちはとても情が深いんです」

そう目を細める杉山さんは1945(昭和20)年8月の敗戦までの4年余り、日本が支配した植民地朝鮮で国民学校(小学校)の教壇に立った。戦時下の皇民化教育。朝鮮の子どもたちを立派な日本人にするのが教師の使命と信じた。

戦後は、戦争教育に関わったことへの自責の念にさいなまれ、教え子との再会を通じて、その苦しみを和らげていく。杉山さんが歩んだ人生は、戦後76年が経過し、戦争を体験した世代が少なくなるなか、貴重な歴史の証言として現代に重く響く。

父・源次郎さんと母・さとさんは富山県旧杉原村で本家の田畑を耕していた。日本が大韓帝国(当時の国号)を併合した後、父は単身、海を渡って朝鮮で生活基盤を築いた。母は四つ上の兄・正雄さんを抱いて後を追った。

両親は朝鮮半島南西部、全羅南道の霊光の農村を新天地に定め、果樹園を経営した。やがて21(大正10)年、杉山さんが生まれる。

霊光で暮らしたのは3歳ぐらいまで。兄が小学生になったが、自宅から歩いて通えないほど遠かった。両親は子どもの教育のため都市への移住を決め、果樹園を手放すことにした。

「生まれ故郷」の穏やかな農村風景は、果樹園の道沿いに咲く白いアカシアの花とともに、杉山さんの脳裏にかすかに浮かぶ。

一家は朝鮮半島南東部にある慶尚北道の中心都市、大邱に移り住む。両親は市中心部の「元町1丁目」に帽子店を構えた。屋号は富山の「富」の字をとって「富屋帽子店」にした。

店では2人の朝鮮人の青年が住み込みで働いていた。両親とも朝鮮語は話せず、朝鮮人の来客があると2人が応対した。「和吉」「一郎」という日本式の名前で呼んでいた。

自宅兼店舗があった目抜き通りの商店主は、ほとんどが日本人だった。朝鮮の人々の多くは日本人に使用される立場で、少し離れた地域に集まって住んでいた。杉山さんの幼少期の記憶に残るのも日本人ばかり。朝鮮人の子どもと遊んだ記憶はない。

大邱に限らず、植民地朝鮮に移住した日本人は固まって生活し、和風の家屋が立ち並ぶ「日本人街」を形成した。日本人と朝鮮人の子どもが通う学校もほとんどが別々で、杉山さんが通った小学校や高等女学校の同級生も日本人だけだった。今考えると、「いびつな植民地」だった。

「併合については『仲良しだから、日本と朝鮮は一緒になった』と、子どものころ学校で教わりました。だから、罪悪感なんて少しもありませんでした」と、杉山さんは振り返る。

女学校時代でよく覚えているのは「内地」への修学旅行だ。朝鮮で生まれ育った杉山さんにとって、内地は「心しびれるような憧れの地」だったという。

韓国併合 日本は明治期、朝鮮の権益などを巡るロシアとの戦争を経て1905年、大韓帝国(当時の国号)を保護国にし、統監府(初代統監・伊藤博文)を開設する。外交権剝奪(はくだつ)や軍隊解散など支配権限を段階的に強め、10年8月の併合条約で植民地にした。

最終学年の5年生になった38(昭和13)年。日中戦争のさなかで、日本軍の「徐州陥落」を祝って昼は旗行列をし、夜は提灯(ちょうちん)行列で練り歩いた翌朝、慌ただしく出発した。釜山から船で下関に渡り、京都や奈良、鎌倉などを巡った。移動中、車窓から目にした朝焼けの富士山の姿は忘れがたい思い出になった。

当時の朝鮮では女学校を出ると、お稽古事など花嫁修業をすることが多く、母親も「職業婦人」などもってのほかと考えていた。

しかし、杉山さんは自立したいと望んでいた。学校の掲示板に「京城女子師範学校」の募集案内を見つけた。熱心な教員志望ではなかったが、受験を決めた。猛反対する母親を担任教師に説得してもらった。教壇に立つ岐路になった。

◇

記者が杉山さんに会った理由

2016年8月15日、朝日新聞(大阪本社版)の読者投稿欄「声」の特集「平和と戦争」に、「『自分の国』一瞬で砕け散る」との見出しで、杉山とみさんの投稿が載りました。

日本と朝鮮半島の関係史を取材してきた記者は、ソウル在勤中(11~14年)を含め、日本支配下で「皇民化教育」を受けた韓国の人々や、植民地朝鮮で暮らし、戦後日本に引き揚げた人々の取材を重ねてきました。しかし、植民地朝鮮で教壇に立った方に出会う機会はありませんでした。早速、杉山さんを訪ねて話をうかがい、教え子との交流が続いていることに驚きました。「皇民化教育」に携わった日本人は戦後恨まれたのでは。そんな先入観がありましたが、杉山さんは違いました。

杉山さんのもとを何度か訪ね、手紙や電話でやりとりを重ねるうち、なぜ杉山さんが教え子から慕われたのかが少し分かったように感じました。

1945年8月15日の敗戦で「植民地という幻」(杉山さん)は崩れます。朝鮮の子どもを立派な「皇国臣民」にすることが責務と信じていた杉山さんは、過去を見つめ直します。約30年後の再会で杉山さんは後悔の念を述べ、教え子の信頼は深まったのです。

日韓関係がこじれる中、杉山さんの足跡は隣国との関わりを考える糸口になるのでは。そんな思いから、杉山さんが100歳を迎えた今夏、その半生を紹介したいと思いました。(中野晃)

あの海の向こうに ~植民地で教えた先生~②(全5回)

日中戦争は泥沼化し、欧州で第2次世界大戦が勃発する1939(昭和14)年。植民地朝鮮で生まれ育った杉山とみさん=富山市=はこの年の春、大邱高等女学校を卒業し、ソウルにあった「京城女子師範学校」の演習科に入学した。

当時17歳。親元を離れての寮生活に心躍ったが、外出は自由にできず、規則による統制は厳しかった。起床や消灯の合図では軍隊式のラッパの音が響きわたった。戦意高揚のためか、敷地内には戦闘機が置いてあった。

生徒は朝鮮各地のほか「内地」からも集まっていた。同級生が日本人だけだった女学校までとは異なり、日本人と朝鮮人の生徒が机を並べて学んだ。

朝鮮総督府が設置した官営学校だけあり、教育内容は徹底して「皇民化」を目指すものだった。

校舎でも寮でも口にできるのは日本語だけ。「吾等恵まれて皇国(スメラミクニ)に生まる」にはじまり、皇国臣民としての大義を説く校訓をまず頭にたたきこまされた。

授業はすべて日本に関する内容だった。国語では清少納言など日本の古典を学んだ。音楽では、君が代と日本軍歌の「海ゆかば」、日本の祝日である紀元節など四大節の唱歌をオルガンで弾けるようになることが必須の課題だった。

真冬に吐息がまつげに凍り付くような厳寒のなか、仁川まで一日中歩き続ける「耐寒行軍」という精神鍛錬の行事もあった。

朝鮮の子どもたちを天皇陛下のために尽くす立派な皇国臣民に育てあげる。そんな植民地教育の先頭に立つ教員養成が師範学校の役目だった。

杉山さんは身の引き締まる思いで日々の授業にのぞんだ。もともとは熱心な教員志望ではなかったはずだが、まじめに学ぶうちに、真綿に水が染みこむように自身の「皇民化」はすすんでいた。

しかし、朝鮮人の友人の内心は違っていたのかも知れない。後でそう考えさせられる出来事が起きた。

教育勅語を暗記する宿題が課されたが、その友人は忘れてきた。教師に理由を問われてこう答えた。

「覚えたくなかったからです」

教師は怒り、寮友の杉山さんを呼び出し、友人の生活態度を問いただした。

「決して不敬ではなく、思想的反抗でもないと思います。怠けたことを一番まずい言葉で言ってしまったのではないでしょうか」。必死に友人をかばった。

のちに振り返り、友人の本心がにじみ出たのだろうと思った。皇民化教育に対する抗(あらが)いの意思を精いっぱい示そうとしたのだと。

面従腹背。日本支配を受け入れているように見えた朝鮮の人々の心の奥底は違っていたことを、杉山さんは敗戦後に悟る。

教育勅語 明治天皇から1890年に「下賜(かし)」され、親孝行などの徳目や、危急の事態には皇室の運命を助けるよう臣民に教示した。昭和の敗戦まで国民道徳や国民教育の根本理念とされた。戦後の1948年、衆院で排除、参院で失効確認の決議がされた。

戦争の時代だったが、楽しい思い出もある。

寮で食べるキムチは全校生徒が協力して作り、かめに漬けた。新入生歓迎会は夜桜見物。規律が厳格な学校生活で唯一認められた夜間外出の機会だった。

修学旅行の行き先は旧満州(中国東北部)だった。満州国(32~45年)は日本軍が駐屯し、南満州鉄道など日本の国策会社が経済を掌握。国際社会が「傀儡(かいらい)国家」と指摘したように日本の勢力下で、朝鮮から鉄路での旅行が可能だった。

41(昭和16)年の春、杉山さんは師範学校を卒業する。入学前は進学に反対した母親がみずから卒業式に駆けつけた。

新任教員として赴任が決まったのは、出身地の大邱にあり、朝鮮人の子どもたちが通う達城公立国民学校だった。戦時色が濃くなるなか、小学校などの初等教育機関はこの年から「国民学校」に改名された。

まだ数えで二十歳だった杉山さんは、活力と責任感にあふれていた。

朝鮮の子どもたちを立派な日本人、立派な皇国臣民に育てあげる。それこそが教師の責務だと信じ、教壇に立った。(中野晃)

あの海の向こうに ~植民地で教えた先生~③(全5回)

太平洋戦争が始まる1941(昭和16)年の春、杉山とみさん=富山市=は植民地朝鮮の大邱で初めて教壇に立った。朝鮮人の子どもたちが通う達城国民学校で4年生を受け持った。

朝鮮語の使用は絶対禁止。皇居の方角に頭を下げる「宮城遥拝(ようはい)」、天皇皇后の御真影と教育勅語をおさめた奉安殿への最敬礼を繰り返させた。「私共は心を合わせて天皇陛下に忠義を尽くします」などと声をあげる「皇国臣民ノ誓詞」の復唱も連日させた。

2年目には1年生の担任に。入学式の日、杉山さんは新入生の服の胸部に、創氏改名した日本式の氏名を書いた名札を縫い付けた。

創氏改名 朝鮮総督府が皇民化政策の一環で1939年、朝鮮民事令を改正し、40年に実施。朝鮮の姓名から日本式の氏名にするよう求めた。伝統的に祖先を重用する朝鮮の人々に対し、応じなければ不利益を被るとして職場や学校などを通して届け出を迫った。

運動場での青空教室。杉山さんが「すわりなさい」と呼びかけると、子どもたちは「スワリナサイ」と声をそろえてまねした。1年生はまだ日本語が分からなかった。「一日も早く日本語を覚えさせなければ」。そんな思いを強くした。

いま、杉山さんは「子どもたちはどんなにもどかしかったでしょう」と想像する。不慣れな日本式の名前で呼ばれ、何よりも自分たちのことばを口にできず、つらかっただろうと。

学校行事は戦争色が濃くなっていた。学芸会では、後醍醐天皇のために命を奉じたと敬われた武将、楠木正成が主役の「大楠公(だいなんこう)」を子どもらに演じさせた。戦地の兵隊に送る慰問袋に入れる絵巻物も作らせた。軍部に献上する「国防献金」のため、松笠拾いやタニシ捕りをさせた。

国民学校には朝鮮人の教員もいたが、待遇に差があり、日本人だけ上乗せの手当があった。新任の杉山さんの給与は、家庭をもつ朝鮮人の先輩より高かった。

職員朝礼は校長室の神棚の前であり、楠木正成が後醍醐天皇への忠義を詠んだという歌を全員で朗詠し、心身を引き締めた。

戦時統制が強まるなか、衝撃的な出来事が起きる。

日本の憲兵が突然、学校にやって来て、2人の若い朝鮮人の男性教員を連行したのだ。ほかの教員に何ら説明はなく、2人が学校に戻ることもなかった。

憲兵隊は日本支配に抵抗する独立運動に目を光らせていた。朝鮮の言語や文化を消し去ろうとする「皇民化教育」の一端を担わされながらも、日本人には明かさない秘めた思いがあったのだろうか。

日本の敗戦による解放後、杉山さんは、このうちの1人の先生が「独立準備委員会」という腕章をしている姿を目にする。

朝鮮人を立派な皇国臣民にしようとする学校生活で教え子たちの脳裏に長く刻まれた授業があった。

4年生女子の裁縫の授業。日本と朝鮮では針の運び方や継ぎ布のあて方も異なるが、和裁の基礎を教えるよう求められていた。

あるとき、子どもたちが「ポソン」の縫い方を教えて欲しいと声をあげた。つま先がとがった長靴のような形をした朝鮮の足袋だ。生活に根ざした裁縫の方が子どもたちの役に立つだろうと、杉山さんは日本語が堪能な母親に学校に来てもらい、一緒に授業をした。

「あくまでも秘密の型破りな授業でした。校長に知れたら呼び出されて大目玉をくらったか、始末書ぐらいは書かされたでしょう」と杉山さんは話す。

そんな授業をしたこともすっかり忘れていた。

戦後三十余年たち、教え子たちと韓国で再会して思い出を語り合ううち、「杉山先生、学校でポソンを縫いました。私たちはよく覚えていますよ」と言われ、はっと思い出した。

国民学校で、子どもたちの願いに少しでも応えようとしていた若い日の自分の姿がよみがえった。

ことばも、名前も、生活習慣も。何もかも日本式を子どもの意識に植え付けようとした皇民化教育。当時は教師の責務と信じこみ、日々の授業に打ち込んだ。

しかし、振り返ると、内心は少しは疑念を抱いていたのかも知れない。そんな自分にほっとした。(中野晃)

あの海の向こうに ~植民地で教えた先生~④(全5回)

つらい出来事で、いつだったか記憶も薄らいだ。

植民地朝鮮の大邱で暮らしていた杉山とみさん=富山市=の家に太平洋戦争後期、四つ上の兄が南方で戦死したことを知らせる通知が届いた。

どこで、どうして兄は死んだのか具体的な情報は伝えられず、遺骨も遺品も届かなかった。兄は結婚して間もなく出征した。新妻との間に双子の娘が生まれたことも知らず、父の帽子店を継ぐ夢も断たれた。

1945(昭和20)年1月、杉山さんは4年近く教壇に立った達城国民学校から、大邱師範学校付属国民学校へ異動になった。

「内地」は米軍の無差別爆撃を受けるようになり、大勢の市民が犠牲になった。朝鮮は本格的な空襲に見舞われることはなかったが、学校では連日のように防空壕(ごう)への避難や機銃掃射から身を守る訓練を繰り返していた。

45年8月15日。

学校は夏休み中だった。正午に重大放送があるとの知らせが入り、ラジオの前で耳をすませたものの、よく聞き取れなかった。一緒に聞いた父は黙っていた。夕方近くになり、町中が歓声で騒然とし始めた。

「トンニプ、マンセー(独立、万歳)」

日本の敗戦を知った。朝鮮の人々にとっては35年間に及んだ日本統治からの解放を意味した。

「日本が戦争に負けるなんて思ってもいなかったし、負けたら朝鮮が独立するということもまったく想定していませんでした」

そう振り返る杉山さんは生まれ育った朝鮮でずっと教員として働き続けるつもりでいた。ほかの在朝日本人の多くも同じように考えていただろうと思う。しかし、「植民地という幻」は一瞬にして砕け散った。

一夜明けた8月16日早朝、杉山さんは大邱の郊外を目指した。母や戦死した兄の妻、幼い双子のめいが疎開している農村に迎えに行くためだった。

バスターミナルで列に並んでいると突然、朝鮮人の青年が声をかけてきた。

「娘さん、あんたは日本人だね。もうここは日本ではないんだから、日本人は下がってもらおう」

そう言って目の前に割り込み、列からはじき出された。ショックで言葉が出なかった。乗車をあきらめ、ひとりで歩き始めた。

しばらくして「先生」と呼ぶ声が聞こえた。達城国民学校で初めて受け持った4年生の教え子で「慶金正燮(よしかねせいしょう)」(本名・金正燮(キムジョンソプ))という少年だった。目的地まで案内するという教え子の自転車に乗せてもらった。

田園道を走っていると、大勢が町の方へと歩いて来る。何の人並みだろうと金少年と話をしているうち、すれ違った人から突然、朝鮮語で怒声を浴びた。

「今の人何て言ったの」「聞かない方がいいです」。何度も聞き返すと、金少年が答えた。「あの人は『日本語を使うな。朝鮮語で話せ』と言ったのです」

杉山さんは思わずその場で声をあげてしまった。

「日本語を使って、何が悪いのよ」

冷静になり、はっとした。自分自身こそ朝鮮の子どもたちに朝鮮語を使わず、日本語で話すよう日々命じていた。そのことに気付き、がく然とした。

在朝日本人 朝鮮には敗戦時、70万人超の日本人がいたとされるが、ソ連軍が占領した北緯38度以北からの引き揚げは困難を極め、飢えと寒さで大勢が死亡した。技術者らは当局が帰国を許可せず、朝鮮人男性と結婚した日本人女性など残留した人も少なくない。

家族と合流して大邱の帽子店に戻った。住み込みで働いていた朝鮮人の青年の姿は消え、店を閉めたまま家にこもっていた。

やがて勤務先の学校から職員集合の号令がかかった。運動場の一隅に大きな穴を掘り、書類や書籍、神棚などを運び入れては火をつけた。皇民化教育の痕跡を灰にした。

たちのぼる赤い炎を前に杉山さんはぼんやりとしていた。「今までの日々はいったい何だったんだろう」

朝鮮の子どもたちを立派な皇国臣民に育てあげるのが使命と信じ、教育に打ち込んだ日々。それまで築きあげたものが瞬時に崩れ落ち、心の中にぽっかりと空洞が広がる気がした。(中野晃)

あの海の向こうに ~植民地で教えた先生~⑤(全5回)

釜山港を船が離岸するとき、生まれ育った朝鮮での日々が目に浮かんだ。

1945(昭和20)年秋、杉山とみさん=富山市=は引き揚げ船で24年余り暮らした朝鮮を去った。

福岡から列車を乗り継いで両親の郷里の富山に戻り、旧杉原村の親類宅に身を寄せた。慣れない農作業に汗を流し、行商もした。

皇民化教育の最前線で戦争に協力したという後ろめたさと、朝鮮の教え子たちへの申し訳なさから「二度と教壇に立つまい」と心に誓っていた。

だが、戦後の教員不足の中、たびたび教職復帰の誘いが来た。「困っている子どもがたくさんいる」と説得され、47年、出産で休む教員の後を受けて小学校の教壇に立った。教える内容は様変わりしていた。

一方、朝鮮半島は激動期が続いた。解放後、北緯38度線を境に南側を米軍、北側をソ連軍が分割占領した。48年には韓国と北朝鮮が相次いで建国し、南北に分断される。

引き揚げまで杉山さん一家を助けてくれた大邱の達城国民学校の教え子、金正燮(キムジョンソプ)さんからは再会を願う手紙が富山に届いたが、やがて朝鮮戦争(50~53年)で音信不通になった。

札幌冬季五輪大会が開かれた72年、思わぬ形で金少年の消息を知った。札幌駐在の韓国領事として活躍していた。夫人は杉山さんを慕っていた教え子の金三花(キムサムファ)さんだった。五輪後、27年ぶりの再会を果たし、3人で一緒に「春の小川」や「アリラン」を歌った。

76年、杉山さんは帰任していた金夫妻の招待を受け、31年ぶりに「生まれ故郷」の韓国を訪ねる。ソウルの金浦空港では教え子や師範学校時代の同窓生が出迎えてくれた。

4年余り教壇に立った大邱にも向かった。バスが着くと、民族衣装姿の女性が「先生」と駆け寄って来た。手をとりあった。

歓迎の宴で、杉山さんは皇民化教育でみんなを無理に日本人にしようとしたと過去を振り返り、わびた。ずっと自責の念にさいなまれ、口にせずにはいられなかった。教え子たちはただ静かに話を聞いていた。

日本や日本人への不信感からか、出席を拒んだ教え子もいた。「先生が謝罪した」と伝え聞いたようで、その後の訪韓時には姿をみせてくれた。

気がかりなままの教え子がいる。達城国民学校の4年時に担当した朴小得(パクソドゥク)さん。卒業後、当時の担任らに「働きながら勉強もできる」と勧められて「女子勤労挺身(ていしん)隊」に加わり、富山の軍需工場に動員された。

杉山さんは両親の郷里が富山だと教え子らに話していた。なじみのある地名に手をあげたのではと心にひっかかっていたが、戦後の消息は分からなかった。

93年、元挺身(ていしん)隊員らが日本政府に損害賠償を求めた訴訟の原告の一人として朴さんは来日する。杉山さんに会いたがっていると伝え聞き、福岡の支援者集会に駆けつけ、あいさつした。

「祖国の言葉を封じ込め、戦争教育をしたことを心からすまないと思います。そんな私を慕い続けてくれる朴さんには、胸が張り裂けそうな思いです」

勉強など全然できなかった。せめて賃金は払ってほしい――。そんな朴さんらの訴えに日本政府や企業は応じず、司法も追認した。

無念さが晴れぬまま、朴さんはすでに他界した。教え子の力になれなかったという悔いは消えない。

戦後補償 日韓は1965年の国交正常化で請求権協定を締結。日本政府は協定で「完全かつ最終的に解決された」との立場だ。一方、韓国大法院(最高裁)は2018年、元徴用工ら個人の請求権を認めて日本企業に賠償を命じ、外交問題になっている。

韓国で小説の賞をとった教え子もいる。絵日記を杉山先生にほめられたことで作家を志したと彼は言った。自身は忘れていた。教師の言葉の重さを悟った。

戦後、富山で約27年間小学校教員を務めた。退職後、県内の民間団体の日韓交流事業に参加し、何度も訪韓した。還暦を過ぎて学び始めた韓国語に好きな格言がある。

〈ゆく言葉が美しければ 返ってくる言葉も美しい〉

互いに思いやりのある言葉を発せば、こじれた日韓関係もほぐれるはずです。

杉山先生からの伝言だ。(中野晃)