Niece of Korean collaborator nobleman Yoon Deok-yeong (윤덕영, 尹徳栄) was featured in 1939 article declaring ‘I really want to marry a Japanese man’ and adopting the Japanese surname ‘Izu’ to improve her marriage prospects

2024-04-14

422

721

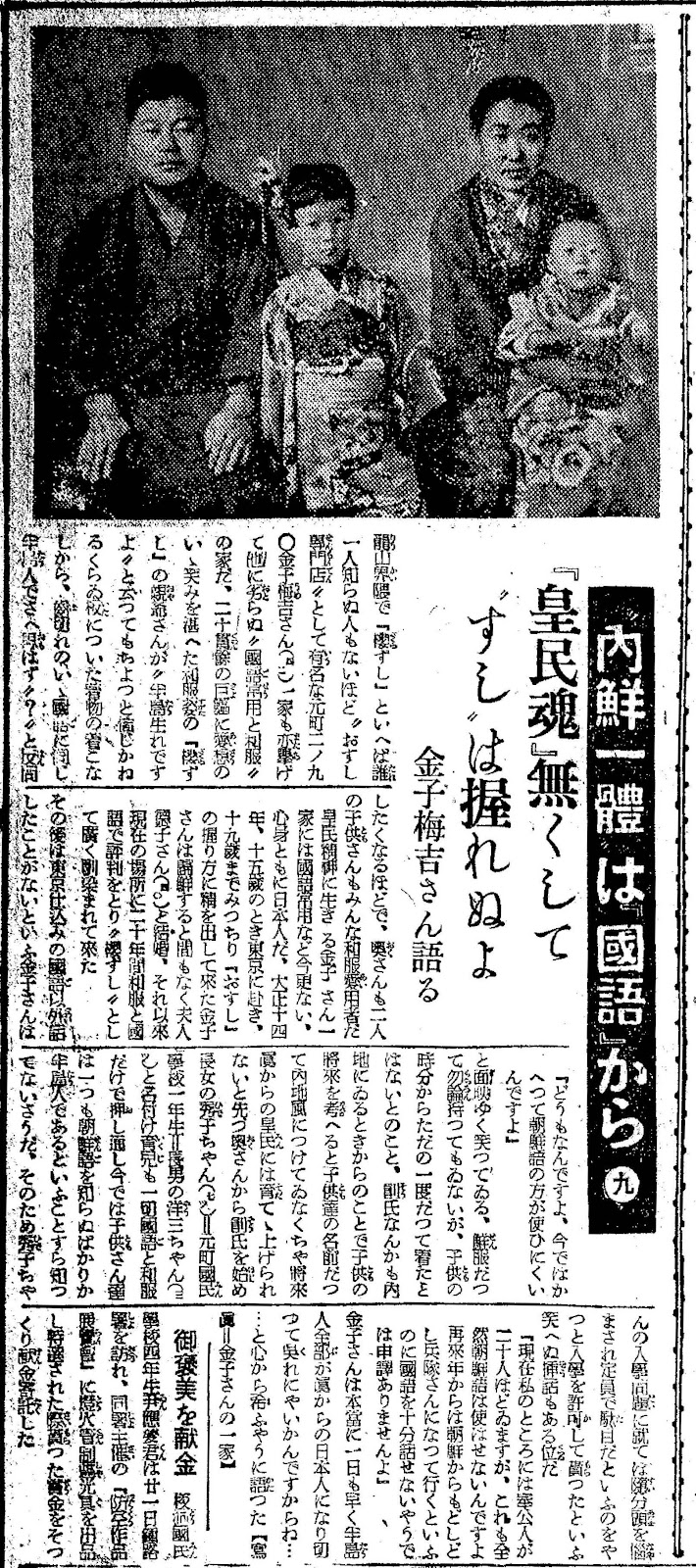

The following article from 1939 features a young 21-year-old Korean woman celebrating her newly given ability to change her surname to a Japanese one so that she can find a Japanese husband more easily. This story was presumably published to encourage Koreans to adopt Japanese last names in the wake of a November 1939 ordinance that was issued to require the creation of Japanese family names for all Koreans.

This young Korean woman was not just any woman, but the niece of a prominent Korean nobleman, Yoon Deok-yeong (윤덕영, 尹徳栄), who is widely reviled in Korea today as a pro-Japanese collaborator. Even being a distant relative of the prominent nobleman appeared to confer advantages for her, since she was able to find employment at Sanseido, a renowned publishing company known for its dictionaries.

Published in Keijo Nippo, the colonial newspaper and official mouthpiece of the Imperial Japanese government that ruled Korea from 1905 to 1945, one propaganda purpose of this article was probably to encourage Korean women to adopt Japanese surnames by enticing them with the prospect of attracting Japanese men more easily. Another propaganda purpose was probably to encourage Japanese men to consider marrying Korean women, as a part of the overall Japanese-Korean Unification (naisen ittai, 内鮮一体) policy of Imperial Japan.

[Translation]

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) November 14, 1939

A hopeful start toward the unification of the “family system” [4]

“I really want to marry a Japanese man,” says Miss Yoon, relieved from her worries

“It is quite absurd to have two surnames within the same country. Having two surnames naturally divides people, doesn’t it? The Japanese language is used as the standard language, while the Korean language is only for home use. Furthermore, Korean is just a local language understood only by people like my parents who don’t know the standard language.”

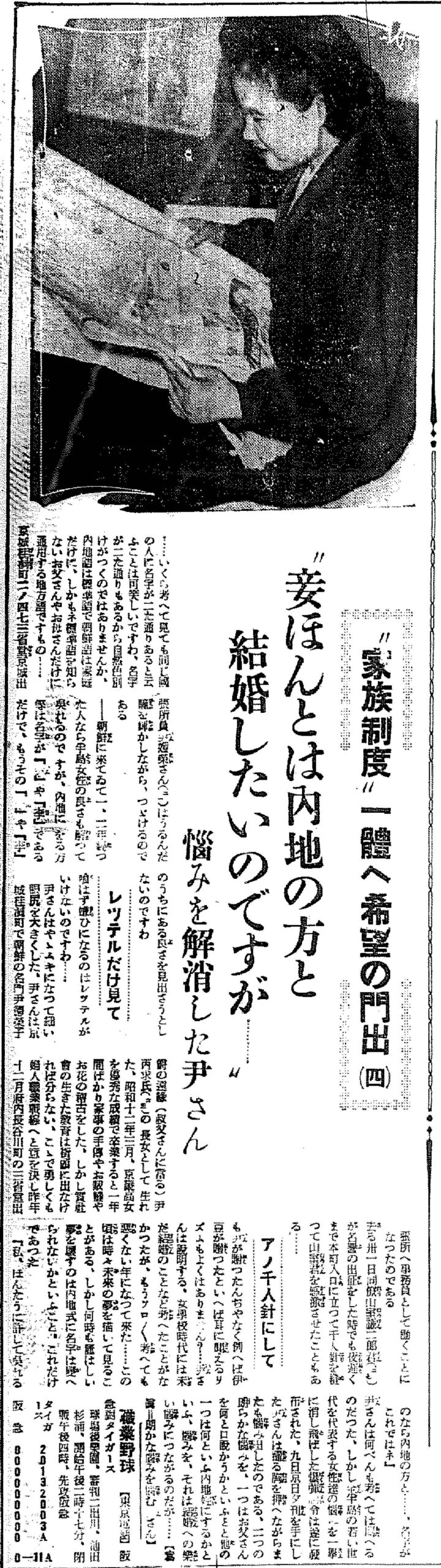

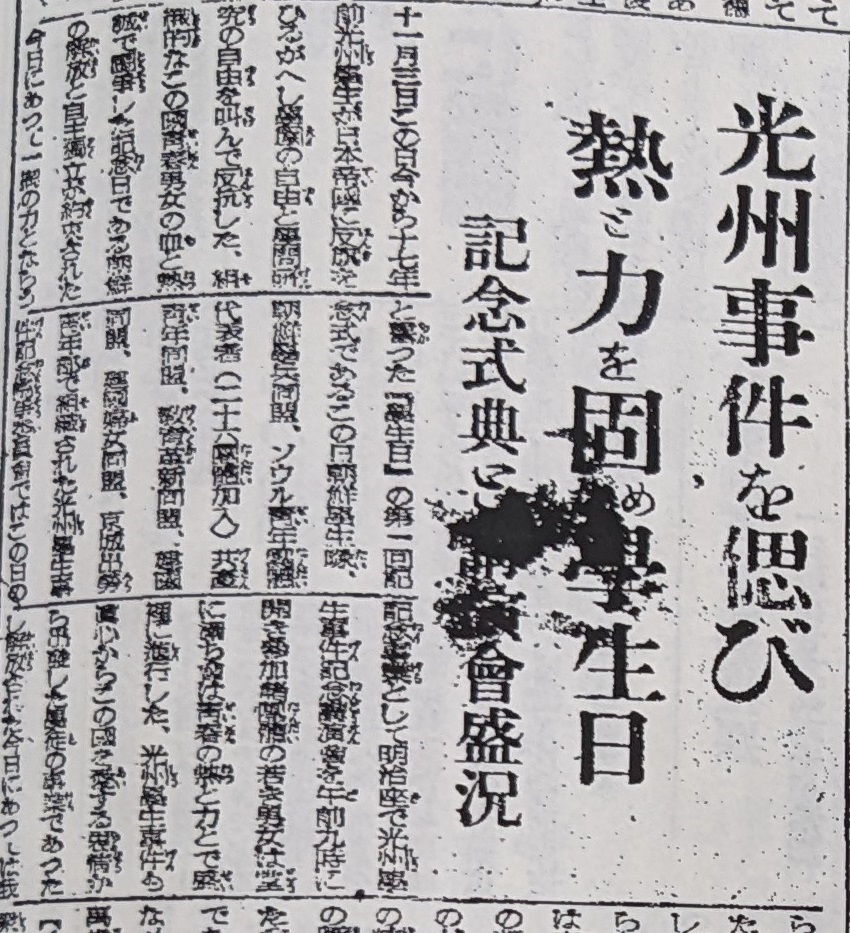

Miss Yoon Hee-yeong (윤희영, 尹嬉栄) lives in 2-47 Gye-dong, Seoul, and she is a 21-year-old employee of Sanseido Seoul branch. She continues with glistening eyes:

“If any man comes and spends time in Korea for a year or two, he would understand the merits of Korean women. However, Japanese men judge women merely for having surnames like ‘Yoon’ or ‘Lee’, failing to see the goodness within those names.”

“It’s wrong to dislike someone just based on labels,” Miss Yoon argued, her eyes widening slightly. Miss Yoon was born in Gye-dong, Seoul, as the eldest daughter of Yoon Byeong-gu (윤병구, 尹丙求), who is the brother of the great nobleman Yoon Deok-yeong (윤덕영, 尹徳栄). After graduating with honors from Gyeonggi Girls’ High School in March 1937, she helped with household chores, sewing, and flower arrangement for about a year.

But she realized that it was hard to get a real-world education unless she went out into the streets. Bravely deciding to join the women’s professional front, she started working as a clerk at a branch of Sanseido in Hasegawa-chō (present-day Sogong-ro) in Seoul last December.

On the 31st of last month, even when her colleague Kenjirō Yamamuro (27 years old) was honored with military deployment, Miss Yoon stayed up late at the entrance of Honmachi District, sewing a Sen’ninbari amulet, which deeply moved Mr. Yamamuro.

“Instead of saying that Miss Yoon sent the Sen’ninbari amulet, doesn’t it sound more pleasing to the ear with better rhythm if you say that Miss Izu sent the amulet?” Miss Yoon explained. She had never thought about marriage during her school days, but now she feels that it is not a bad time to start considering it at her age. Lately, she occasionally dreams of the future. However, her beautiful dreams had always been marred by the impossibility of changing her surname to a Japanese one.

“If I am really permitted to do so, I’d like to marry a Japanese man … but with my current surname, it’s tough,” Miss Yoon repeatedly contemplates and agonizes. However, a groundbreaking decree that instantly alleviated the worries of a generation of young women across the Korean peninsula was finally issued. Holding the evening edition of the Keijo Nippo Newspaper from the 9th, Miss Yoon began to worry again while, at the same time, she suppressed the excitement in her chest. Her two cheerful worries were about how to persuade her father and what Japanese surname to choose, leading to her delightful worries about marriage.

[Photo caption: Miss Yoon pondering her cheerful worries]

[Transcription]

京城日報 1939年11月14日

”家族制度”一体へ希望の門出(四)

”妾ほんとは内地の方と結婚したいのですが”

悩みを解消した尹さん

いくら考えて見ても同じ国の人に名字が二通りあると云うことは可笑しいですわ。名字が二通りもあるから自然色別けがつくのではありませんか。内地語は標準語で朝鮮語は家庭だけに、しかもね、標準語を知らないお父さんやお母さんだけに通用する地方語ですもの。

京城桂洞町2の47、三省堂京城出張所員尹嬉栄さん(21)はうるんだ瞳を輝かしながら、つづけるのである。

朝鮮に来ていて一、二年経った人なら半島女性の良さも解って呉れるのですが、内地におる方等は名字が「尹」や「李」であるだけで、もうその「尹」や「李」のうちにある良さを見だそうとしないのですわ。

レッテルだけ見て喰わず嫌いになるのはレッテルがいけないのですわ。尹さんはややムキになって細い目尻を大きくした。尹さんは京城桂洞町で朝鮮の名門尹徳栄子爵の遠縁(叔父さんに当たる)尹丙求氏の長女として生れた。昭和十二年三月、京畿高女を優秀な成績で卒業すると一年間ばかり家事の手伝いやお裁縫やお花の稽古をした。

しかし実社会の生きた教育は街頭に出なければ分からない。ここで勇ましくも婦人職業戦線へと意を決し昨年十二月府内長谷川町の三省堂出張所へ事務員として働くことになったのである。

去る三十一日、同僚山室健二郎君(27)が名誉の出征をした時でも夜遅くまで本町入口に立って千人針を縫って山室君を感激させたこともある。

「あの千人針にしても尹が贈ったんじゃなく、例えば伊豆が贈ったといえば耳に聞こえるリズムもよくはありません?」尹さんは説明する。女学校時代には未だ結婚のことなど考えたことがなかったが、もうそろそろ考えても悪くない年になって来た。この頃は時々未来の夢を描いて見ることがある。しかし、何時も麗しい夢を展ずのは内地式に名字は変えられないかということ、これだけであった。

「私、ほんとうに許して呉れるのなら内地の方と...、名字がこれではね」

尹さんは何べんも考えては悶えるのだった。しかし全半島の若い世代を代表する女性達の悩みを一挙に消し飛ばした爆弾制令は遂に発布された。九日京日夕刊を手にした尹さんは躍る胸を押さえながら、またも悩み出したのである。二つの朗らかな悩みを、一つはお父さんを何と口説こうかということと、他の一つは何という内地姓にするかという、悩みを、それは結婚への楽しい悩みにつながるのだが...【写真=朗らかな悩みを悩む尹さん】

Source: https://archive.org/details/kjnp-1939-11-14/page/n12/mode/1up