“Koreans need to assimilate with the Japanese people as soon as possible … There is no other way. This is also the path to our boundless happiness as Koreans!” said Imperial Army veteran 신태영 in 1943 memoir, who later became Minister of National Defense of South Korea and is now buried at Seoul National Cemetery

2024-06-16

393

3614

“As Koreans, we have been given the new mission of becoming subjects of Imperial Japan, uniting completely with the Yamato (Japanese) people, focusing on Japan to develop, protect, and nurture East Asia. To fully fulfill our mission of sweeping away the gloomy atmosphere of today and achieving renewal, it is imperative that we assimilate with the Yamato people as soon as possible and become completely like them. There is no other way. This is also the path to our boundless happiness as Koreans.“

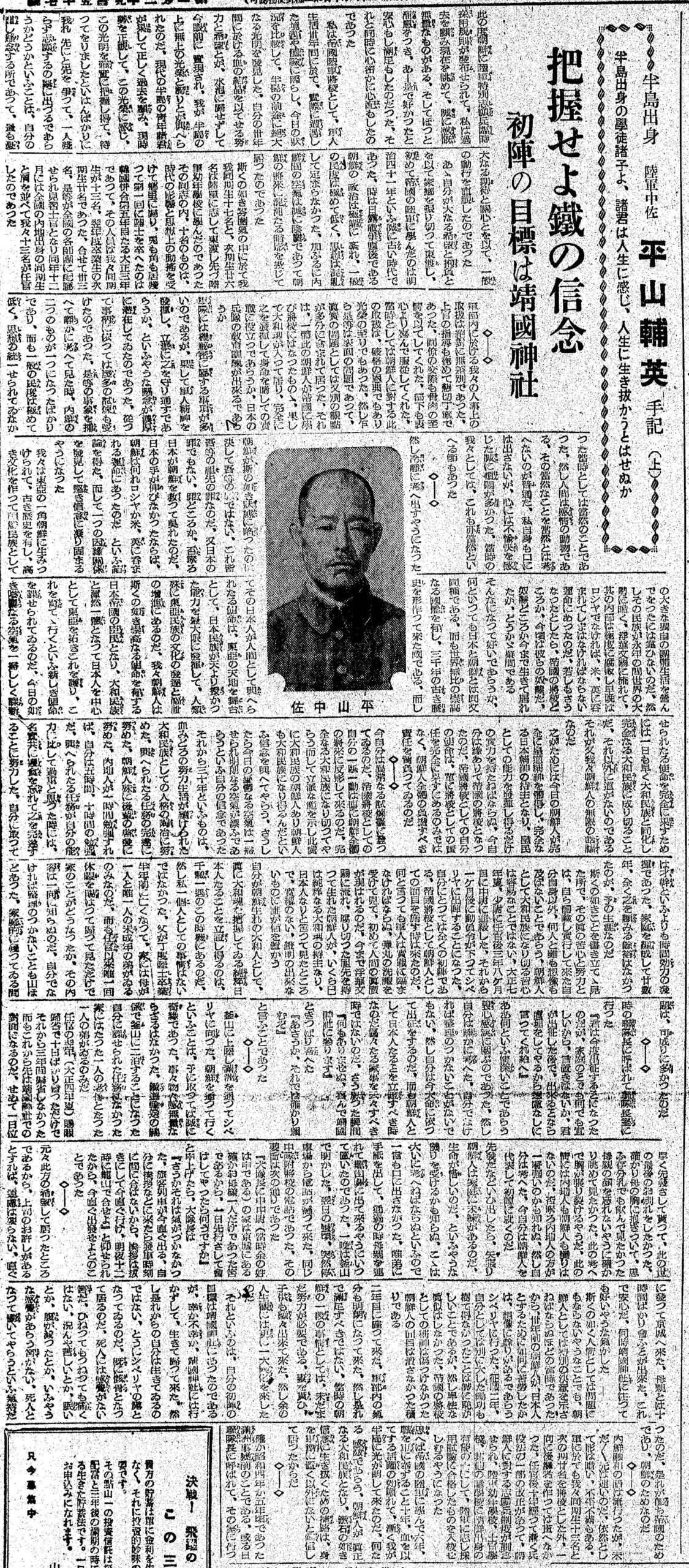

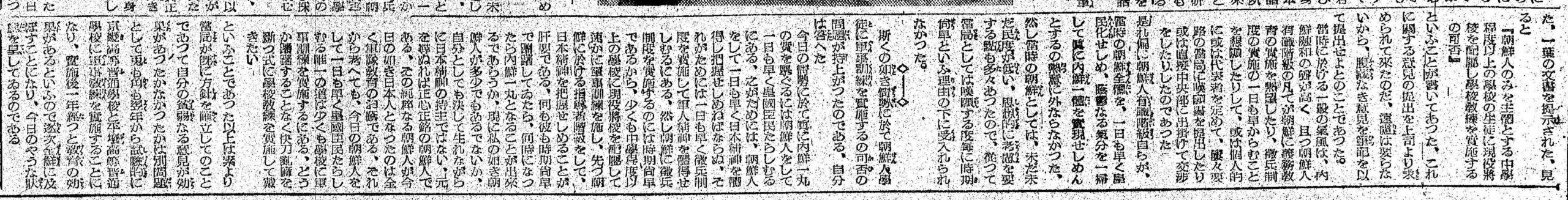

This quote is from a 1943 memoir written below by a prominent Korean collaborator who was in the Imperial Army for over three decades, rising up to become Lieutenant Colonel in the Imperial Army by the 1940s, and then somehow became Lieutenant General in the South Korean Army and Minister of National Defense of South Korea in 1952 and was eventually buried with honors in the Seoul National Cemetery.

It seems baffling and absurd to me that someone who explicitly pledged allegiance to Imperial Japan and renounced his Korean identity could become a high-ranking government official of the Republic of Korea and be honored at its national cemetery. In the memoir, the future South Korean minister declares that Koreans need to assimilate with the Japanese people and become completely like them. He describes how he transformed from a pure Korean into a fully-fledged Yamato person during his decades-long career in the Imperial Japanese Army. The entire memoir reads like a long, passionate ‘love letter’ to Imperial Japan, where his disdain for the Korean nation and his Korean ancestors is quite palpable. So why is he still honored at South Korea’s national cemetery alongside the graves of Korean independence activists?

There is one Korean news article that discusses this very issue, and one Korean journalist posted a YouTube video of himself visiting the actual grave of the collaborator at the cemetery, expressing his disgust at the situation. Angry comments on the video call for the grave to be dug up. But the video has barely gained any traction online, garnering just over four thousand views in four years. The Korean media seem to be aware of the existence of this memoir in the colonial newspaper, but the actual text of the memoir had not been transcribed or translated beyond the headlines until now.

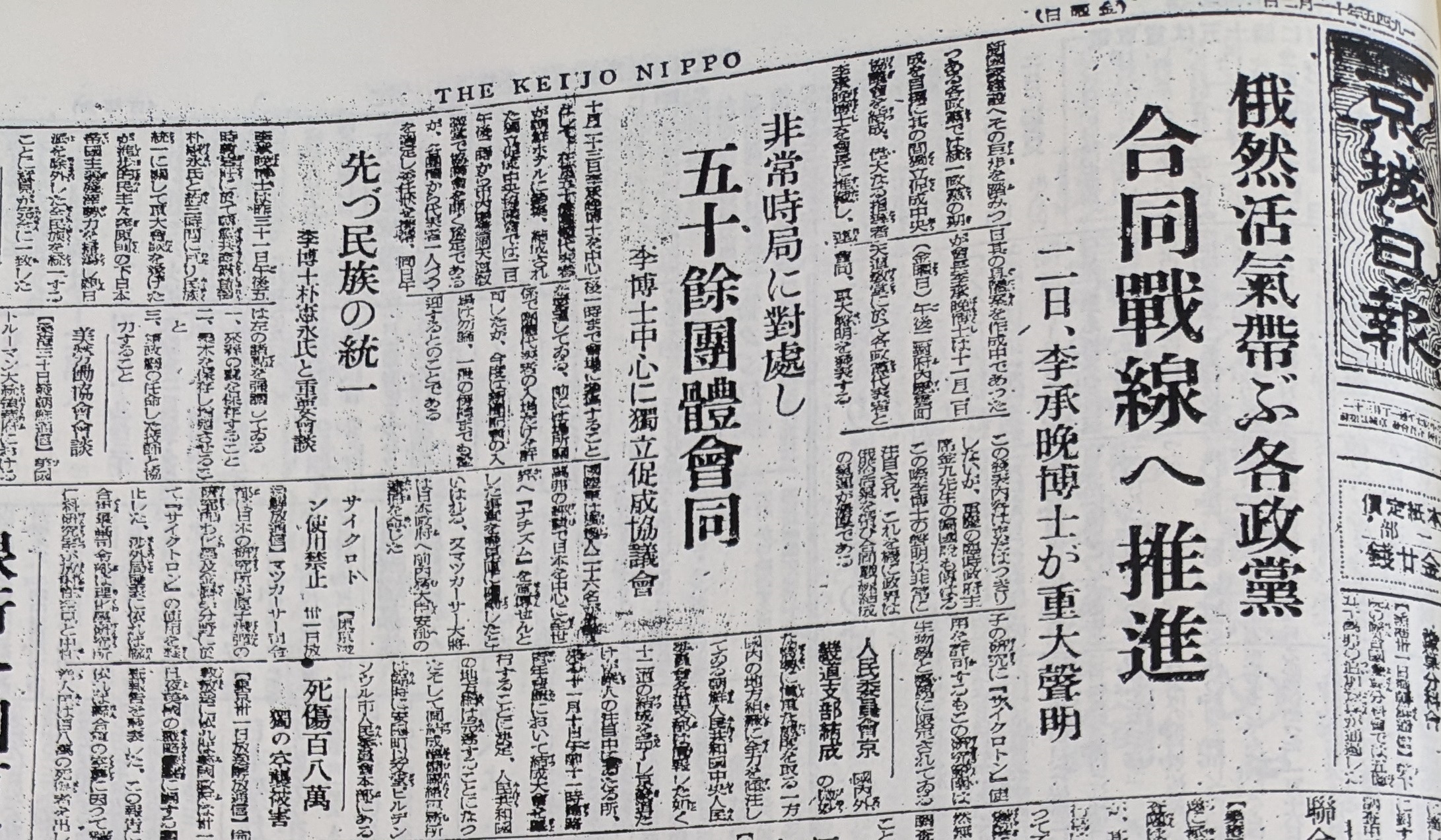

The author of the memoir was Shin Tae-young (신태영) (his original Korean name) or Hirayama Hoei (平山輔英) (his adopted Japanese name). It was published on the front page of the November 17, 1943 evening edition of Keijo Nippo, the national newspaper of colonial Korea and a propaganda mouthpiece of the Imperial Japanese colonial regime that ruled Korea from 1905 to 1945. The colonial newspaper dedicated over half of the front page to this memoir, indicating the importance the colonial regime attached to it to reach as many Korean readers as possible.

In his memoir, Hirayama describes how he trained and served as an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army for three decades, recounting the hardships he endured to fully assimilate into Japanese culture and prove his loyalty to Imperial Japan. He advocates for military training in Korean schools to instill Japanese spirit and discipline, reflecting the views of other ethnic Korean Imperial Army officers like him, including South Korean dictator Park Chung-hee. He saw the Japanization of the Korean nation as the only way to revitalize it and counteract the perceived cultural and ideological decay among the Korean people.

Can you think of any other instance where a person renounces their ancestral country in writing and through service with a military of a foreign country that tried to erase their ancestral country, then later becomes a government official and high-ranking military official of that same ancestral country, and is buried with honors in its national cemetery? To me, it seems quite paradoxical and unjustifiable.

Note: “Yamato people” refers to ethnic Japanese people throughout the memoir. There is a second part to this memoir which was published on November 18, 1943, in which Hirayama mainly goes on to scold Korean families for being reluctant to send their sons off to war, and severely criticizes the Confucian values of Korean culture. If there is interest, I will attempt to decipher and publish it online.

[Translation]

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) November 17, 1943

Memoir by Imperial Army Lieutenant Colonel Hirayama Hoei, an ethnic Korean (Part 1)

Korean students! Do you not want to feel life and live it to its fullest?

Grasp the iron will!

The destination of our first expedition was Yasukuni Shrine

Recently, the Temporary Recruitment Regulations for Special Army Volunteers in Korea were issued, which gave me the occasion to look back on the past and observe the present. As I did so, something filled me with deep emotion. I sighed with relief, feeling both reassurance and satisfaction. Yet, at the same time, I harbored secret worries.

As an officer of the Imperial Japanese Army, reflecting on the situations and experiences I have encountered over thirty years of military life, I compare today’s circumstances and discover a vast light for the future of the Korean peninsula. My thirty years of effort and hope, crystallized from my blood, have not gone in vain. Now, before my eyes, they have materialized, bringing unparalleled honor and pride to our peninsula. Will the modern Korean youth properly reflect on the past, squarely face the present circumstances, feel this honor, and firmly grasp this light? Will they eagerly come forward, as if to say they have been waiting for this moment, and volunteer without exception? This is my concern. I observed their general behavior with the greatest expectation and interest.

It was a long time ago in 1908 when I crossed over to Japan with great hope and ambition, leaving my homeland behind, for the first time to study in the Imperial Army. It was right after the Russo-Japanese War. Korean politics were extremely chaotic, the general level of cultural maturity was very low, and the thoughts of the general public were confused and unsettled. Moreover, the atmosphere between Japan and Korea was genuinely gloomy, casting a shadow over Korea’s future.

In such an environment, my 17 classmates and I, along with 26 students from the next batch of students, aspired to the Imperial Army and crossed over east to Japan to study at the Imperial Army Cadet School. Of these comrades, ten returned home influenced by the times and the ideological turmoil, while the remaining stayed and graduated in the first batch in 1914, during the fifth year of Korea’s annexation. Our group of 13 and the following year’s 20 graduates totaled 33. We were assigned to various divisions nationwide as apprentice officers, and in December of the same year, our group of 13 was commissioned alongside our fellow Japanese graduates.

Our treatment in the military was absolutely non-discriminatory. The guidance from our superiors was extremely kind and meticulous. Our colleagues interacted with us with the utmost sincerity, and our subordinates willingly obeyed us from their hearts. At that time, this treatment of Koreans was an extraordinary privilege and an extreme honor. However, beneath the surface, there were many other viewpoints. Questions lingered, such as whether these Koreans, who had studied in the Empire and become officers, truly possessed the Yamato (Japanese) spirit, fully demonstrated it, and could risk their lives in actual combat. Could they train Japanese soldiers?

The military has many classified matters; would they demonstrate the military spirit and faithfully protect these secrets? Such concerns were deeply latent. Accordingly, we faced many trials depending on the circumstances. Reflecting quietly on these events, it was natural given that Japan and Korea had only just unified, and the general level of cultural maturity was still very low, with the thoughts of hte people not yet unified. However, humans are emotional beings. It is normal for them not to consider the natural course of events as natural. I, too, did not voice it but felt much distress and discomfort in my heart. Given our situation at that time, it could be said that it was also natural to feel this way.

◇―◇

However, when I began to think calmly, I realized that the state Korea had fallen into was not our fault. This was all the fault of our ancestors. Nor was it Japan’s fault. Far from being at fault, Japan had actually saved Korea. If Japan’s hand had not reached out, Korea would have inevitably fallen into the hands of either Russia, the United States, or Britain. This conclusion led me to discover a causal connection and to firmly consolidate my belief.

We were born in Korea, a corner of East Asia, with an ancient history and a high culture, living as a large, unique community as Koreans. However, for many years, our nation had been ignorant of the trends of the world, becoming superficially ostentatious and weak, internally corrupt to the extreme. We were destined to be swallowed up by Russia, the United States, or Britain sooner or later. If that had happened, far from being an officer of Imperial Japan, I would now be a slave of those nations. If I didn’t become their slave, it is doubtful whether I could have even survived.

How could that have been acceptable? Japan and Korea are of the same civilization and race. Moreover, Japan possesses a national polity unrivaled in the world, having shaped a history of three thousand years. The mission entrusted to the Japanese people as human beings is to use their God-given abilities to the fullest on the stage of East Asia, contributing to the development of human culture, especially the welfare and progress of the East Asian peoples. As Koreans, we have been given the new mission of becoming subjects of Imperial Japan, uniting completely with the Yamato people, focusing on Japan to develop, protect, and nurture East Asia. To fully fulfill our mission of sweeping away the gloomy atmosphere of today and achieving renewal, it is imperative that we assimilate with the Yamato people as soon as possible and become completely like them. There is no other way. This is also the path to our boundless happiness as Koreans.

To achieve this, today’s Koreans must fully embody the spirit of the Imperial Way, possessing the complete Japanese spirit, and demonstrating the ability to act as Imperial people. I, now having the opportunity to become an officer of the Empire, recognize my mission is not just to fulfill my responsibilities as an officer but also to shoulder the responsibilities of all Koreans.

◇―◇

I am now being tested at an extraordinary crossroads. My every move as an officer of the Empire directly reflects the future of all Koreans. I must be a fully-fledged Yamato person and set a splendid example, demonstrating that there are Koreans who have become Yamato and instilling the belief that Koreans can also become Yamato people. My belief is that, if I can do this, the gloomy atmosphere of today will be swept away, and a clear air will prevail.

For thirty years, I have lived a blood-soaked life of effort, striving to cultivate my character as a Yamato person, working to complete my given duties, and enlightening my fellow Koreans, especially the younger generation. If a Japanese person studied for one hour, I studied for five or ten hours. When I thought the tasks assigned to me were too heavy compared to my abilities, I worked tirelessly to complete them, forgetting both rest and food. For me, it was more about the efficient use of time than about talent. For more than twenty years, I formed a family, but I had no time to look after it. That has been my life.

Even if I write these things, the true hardship and effort involved are unimaginable to anyone but myself, who has experienced and carried them out. Becoming a complete Yamato person as a Korean is not easy. In the summer of 1918, I was promoted to lieutenant three years and eight months after being commissioned as a second lieutenant. A month later, I received orders for mobilization and was sent to Siberia. It was my first deployment. The time had come to demonstrate my dignity as both an officer of the Empire and a Korean. A soldier must face actual combat to prove his worth. It is only after experiencing the baptism of bullets that a person’s true value is revealed. No matter how much a Korean, born to ancestors who had drifted into superficiality and decay, claims to possess the pure Yamato spirit and to be Japanese, without actual achievements and evidence, who would trust them?

This once-in-a-lifetime opportunity allowed me to prove that I, a Korean-born person, could truly grasp the Yamato spirit and be pure Japanese. However, I did have personal concerns. My father had passed away half a year before my graduation from the military academy, leaving only my mother and one younger brother at home. Since my commission, I had only returned home once on leave, and I had no idea about the state of my household. There were many unresolved matters that only I could handle. The number of family issues remaining was considerable.

◇―◇

I was called by my regimental commander and I went to his office.

He told me, “You are to be deployed soon. If there is anything regarding your family or any other matter, do not hesitate to tell me. After you leave, I will handle it if possible, so feel free to speak up.”

What a deeply compassionate thing to say! I was moved to tears from the bottom of my heart. However, I thought to myself quietly. There were things that could only be settled by myself. Yet, I was now departing by Imperial command. Moreover, this was the time to prove my Japanese identity as a Korean. Now was not the time to be concerned with trivial household matters. Thinking this, I firmly replied, “There is nothing. I will gladly go to Yasukuni Shrine.” “I see. Then I’m counting on you,” he said.

◇―◇

I landed in Busan and headed for Siberia through Manchuria. Passing through Korea felt like a fateful journey. I was overwhelmed with various emotions. Due to the railroad transport arrangements, I stayed in Busan for two nights without any specific duties. At home, I had only my elderly mother and a younger brother.

In the summer of 1915, the year following my commission, I was granted a ten-day leave to return home. Since then, I had not been back for three years. From then on, I would only meet my family at Yasukuni Shrine. I wished I could have departed a day earlier to bid them a final farewell. I wanted to embrace my mother firmly and, if possible, nurse like an infant one last time. I wanted to look at her face to not forget it. This very thought made my heart break. Such feelings are felt by Japanese and Koreans alike. Perhaps Japanese people might feel them even more strongly. However, I thought to myself: I am representing Koreans in my first expedition.

If I mentioned that I wanted to leave early, people might criticize us Koreans by saying that Koreans are too attached to their families and fear for their lives. I had to be very careful, so I said nothing. I only sent a letter to my brother, asking him to bring our mother to Yongsan Station when I passed through. I spent a night in Busan. The next day around noon, I received a sudden phone call from the station. It was from another officer in my company. The gist of the call was as follows:

The officer asked the battalion commander, ‘Lieutenant Shin’s (my surname at the time was Shin) family is in Seoul. Since he only has his mother left, why not let him leave a day early to see her?’ The battalion commander responded, ‘I had never considered that! A passenger train is departing soon. If he comes to greet me, he will miss the departure time. So, let him skip the customary greeting and have him leave immediately. Have him meet his family at Yongsan station at midnight tomorrow.’ So, his orders were that I depart immediately.

◇―◇

Since this was what I had hoped for, I had no reason to hesitate given my superior’s permission. I left immediately and went to Seoul. I was able to see my mother for about ten hours. With that, I felt at ease. I felt ready to go to Yasukuni Shrine at any time.

At the time, even matters that might seem trivial from a human perspective required Koreans to make a special determined effort. So understandably, you can imagine how much hardship Koreans must have had to endure to become Japanese thirty years ago. I went to Siberia and fought for two years. I am ashamed to say that I did not achieve significant military accomplishments, but I did not act cowardly. I upheld the spirit of an Imperial officer and maintained the dignity of the Korean people. After two years, I returned home. The atmosphere within the military became more positive. However, I could not remain sitting on my laurels. Given the situation in Korea at that time, Koreans still needed to put in a lot of effort. I got married, and as children came one after another, my perspective on life underwent a significant change.

Although the initial destination of my first expedition was Yasukuni Shrine, for better or for worse, I returned alive without going there. But from then on, I felt like I was not truly living. I had already died in Siberia. I was already a skeleton. A dead person should not have sensations. Whether I am twisted or pinched, nothing should hurt. Naturally, there should be no sensations of suffering, sleepiness, or hunger. I worked with that kind of mindset of a dead man. This was for Imperial Japan and for Korea.

◇―◇

Though the term “internal harmony between Japan and Korea” was popular, the path ahead was still long. The shadow remained dark. There were still grievances and dissatisfaction. Even in the military, aside from the 13 of us and the 20 officers from the next class, no successors were produced. Ten years after my commission, part of the Military Service Law was amended, allowing for the establishment of a volunteer conscription system for Koreans. Talented students from Korea, who passed the entrance exams, were admitted to military cadet schools, officer schools, and other military institutions.

Thinking back, after six years of studying in the Imperial Army and ten years of serving, my efforts had finally started to bear fruit, bringing light to the Korean peninsula. What a moving moment it was. I had always believed that the best way for Koreans to become true Yamato people and live with unwavering conviction was to join the military.

◇―◇

I believe it was around 1929 or 1930, before the Manchurian Incident. One day, I was called by the regimental commander and went to his office. He presented me with a document. It asked, “Is it feasible to assign active officers to schools primarily attended by Korean students of at least middle school level to implement military training?” My superior was seeking my opinion on this matter. He asked for my frank opinion in writing with no holding back.

At that time, the general mood of the times strongly advocated for harmony between Japan and Korea. The educated Korean class earnestly desired the implementation of compulsory education and the early introduction of conscription. They submitted petitions to authorities in charge, either individually or through representatives, and even traveled to the central government to negotiate directly.

This enthusiasm from the educated Korean class stemmed from a strong desire to transform the entire Korean population into Imperial subjects as soon as possible, sweep away the gloomy atmosphere, and realize true Japanese-Korean unification. However, given the low level of cultural maturity and numerous ideological considerations in Korea at that time, the authorities repeatedly deemed the requests too early to implement.

◇―◇

In this context, the issue of implementing military training for Korean students arose. I responded:

“Given today’s situation, achieving true unity between Japan and Korea requires Koreans to become Imperial subjects as soon as possible. To do this, Koreans must grasp and embody the Japanese spirit as soon as possible. The best way to achieve this is to implement conscription as soon as possible to instill the military spirit. However, it is too early to introduce conscription in Korea. Therefore, at least for now, it is crucial to assign active officers to schools of at least middle school level to provide military training to instill the Japanese spirit and raise a class of leaders. If we keep hesitating by saying that the timing is too early, when will Japanese-Korean unity ever be achieved? There are already some Koreans like me who were not born with the Japanese spirit, because they were originally born pure Korean. It is entirely thanks to military education that a previously pure Korean like myself has become a Japanese today. From this perspective, the only way to make Koreans Imperial subjects as soon as possible is to implement military training in schools. I urge you to implement military training in schools decisively and without hesitation, like cutting through tangled silk with a sharp sword!”

Since the authorities had already established a policy, whether my modest opinion had any effect is another matter. Nonetheless, the following year, military training was experimentally implemented at Gyeonggi High School and Pyongyang High School. After one year, seeing the positive educational effects, the training was gradually extended across Korea, leading to what we now see today.

[Transcription]

京城日報 1943年11月17日

半島出身 陸軍中佐 平山輔英 手記(上)

半島出身の学徒諸子よ、諸君は人生に感じ、人生に生き抜こうとはせぬか?

把握せよ鉄の信念

初陣の目標は靖国神社

此の度朝鮮に陸軍特別志願兵臨時採用規則が発布せられて、私は過去を顧み現在を眺めて、誠に感慨無量なものがある。そしてほっと溜息をつき、ああ是で好かったと安心もし満足もしたのだった。それと同時に心密かに心配もしたのであった。

私は帝国陸軍将校として、軍人生活三十年間に於いて、実際に遭遇した境遇や体験に照らし、今日の状況を比較して、半島の前途に絶大なる光明を発見した。自分の三十年間に於ける血の結晶を以てせる努力と希望とが、水泡に帰せずして今眼前に実現され、我が半島の上に無上の光栄と誇りとが与えられたのだ。現代の半島の青年諸君は果して正しく過去を顧み、現時勢を正視して、この光栄に感じ、この光明を確実に把握し得て、待っておりましたといわんばかりに我れ先にと先を争って、一人残らず志願するの挙に出ずるであろうかどうかということは、自分の蓋し懸念する所であって、最も憂大なる期待と関心とを以て、一般の動行を直視したのであった。

ああ自分が大なる希望と抱負とを以て家郷を振り切って東渡し、初めて帝国の陸軍に学んだのは明治四十一年という誠に古い時代であった。時は日露戦争直後である。朝鮮の政治は極端に乱れ、一般の民度は極めて低く、思想は混乱して定まらなかった。加うるに内鮮間の空気は誠に陰鬱であって朝鮮の将来に混沌たる暗影を投じて居ったのであった。

斯くの如き雰囲気の中に於いて我々同期生十七名と、次期生二十六名は陸軍に志して東渡し先ず陸軍幼年学校に学んだのであった。その同志の内、十名のものは、時代の影響と思想上の動揺を受けて郷里に帰り、兎も角も居残って第一回に陸士を卒えたのは韓国併合第五年目たる大正三年であって、その人員は我々同期生が十三名、翌年度卒業生の次期生二十名であった。合わせて三十三名、是等が全国の各師団に配属せられ見習士官となり同年十二月には全国の内地出身の同期生と肩を並べて我々十三名が任官したのであった。

軍部内に於ける我々の人事上の取扱は絶対に無差別であった。上官の指導も極めて懇切丁寧であった。同僚の交際も骨肉の至情を以てしてくれた。部下も衷心より喜んで服従してくれた。当時としては朝鮮人に対する此の取扱は、破格の恩典でもあり光栄の至りでもあった。然し乍ら是等は表面の問題であって、真実の問題としては又別の観点が多分に含まれて居った。それは、一体此の朝鮮人が帝国に学び将校にはなったものの、果して大和魂が入って居り、完全に之を発揮して身命を賭しての実戦に役立ってあろうか。日本の兵隊の教育訓練が出来るであろうか。

軍隊には機秘密に属する事項が多いのであるが、果して軍人精神を発揮し、立派に之を守り通すであろうか、というような懸念が濃厚に潜在していたのであった。従って事柄に依っては幾多の試練も受けたのであった。是等の事象を捕らえて静かに考えて見た時、内鮮の二つのものが一つになったばかりであり、而も一般の民度は極めて低く、思想の統一せられていなかった当時としては当然のことであった。然し人間は感情の動物である。その当然なことを当然とは考えないのが普通だ。私自身も口には出さないが、心には不愉快を感じた誠に煩悶が多かった。当時の我々としては、これも亦当然といえる節もあった。

◇―◇

然し冷静に考え出すようになった朝鮮が斯の如き状態に陥ったのに決して吾等の罪ではない。これ皆吾等の祖先の罪なのだ。又日本の罪でもない。罪どころか、否寧ろ日本が朝鮮を救って呉れたのだ。日本の手が伸びなかったならば、朝鮮は何れロシアか米、英に呑まれる運命であったのだ、という結論を得た。而して一つの因縁関係を発見して堅き信念に凝り固まるようになった。

我々は東亜の一角朝鮮に生みつけられて、古き歴史を有し、高き文化を作って朝鮮民族としての大きな独自の団体生活を営んでおったには違いないのだ。然しその民族が永年の間世界の大勢に暗く、浮華文弱に流れて、其の内部は極度に腐敗し早晩はロシアでなければ、米、英に呑まれてしまわなければならない運命にあったのだ。若しもそうなったとしたら、帝国の将校どころか、今頃は彼らの奴隷だ。奴隷どころか今まで生きて居れたか、どうかが疑問である。

そんなになって好いであろうか。何といっても日本と朝鮮とは同文同種である。而も世界無比の崇高なる国体を有し、三千年の古き歴史を形作って来た国である。而してその日本人が人間として与えられたる使命は、東亜の天地を舞台として、日本民族が天より授かった能力を最大限に発揮して、人類殊に東亜民族の文化の発達と福祉の増進にあるのだ。我々朝鮮人は斯くの如き崇高なる使命を有する日本帝国の臣民となり、大和民族と渾然一体となって日本人を中心として東亜を拓きこれを護り、これを育てて行くという新しき使命を課せられているのだ。今日の如き陰鬱なる空気を一掃ししく革新せられたる使命を完全に果たすためには一日も早く大和民族と同化し完全なる大和民族に成り切ることだ。それ以外に道がないのである。それが又我々朝鮮人の無限の幸福なのだ。

之がためには今日の朝鮮人が完全に皇道精神を体得し、完全なる日本精神の持主となり、皇民としての能力を発揮し得るだけの実力を持たねばならぬ。今自分は縁ありて帝国の将校となったのだ。帝国将校としての自分の使命は、単に将校としての責任を完全に果たすにあるのみではなく、朝鮮人全体の負担すべき責任を背負っているのだ。

◇―◇

今自分は異常なる試練場に登っているのだ。帝国将校としての自分の一挙一動は直に朝鮮全体の将来に反影して来るのだ。完全なる大和民族になり切ってやろう。而して立派な範を示し此処に大和民族の朝鮮人あり朝鮮人も大和民族になり得るんだという信念を与えてやろう。そうしたら今日の憂鬱なる空気は一掃せられ明朗なる空気が漂うであろうという自分の信念であった。

それから三十年というものは、血みどろの努力生活が続けられた大和民族としての人格の陶冶に努めた、与えられたる任務の完遂に努めた、朝鮮人殊に後輩の啓発に努めた。内地人が一時間勉強すれば、自分は五時間、十時間の勉強だ。与えられたる任務が自分の能力に比して過重と思った時には、名実共に浸食を忘れて之を完遂することに努力した。自分に取っては才幹というよりも時間効力の発揮であった。家庭を編成して二十数年、全く之を顧る余裕はなかったのが、予の生涯なのだ。

斯くの如きことを書き立てて見た所で、その真の苦心と努力とは、自ら体験し実行して来た自分自身以外、何人と雖も想像も及ばないことであろう。朝鮮人として大和民族になり切る苦心は容易なことではない。大正七年夏、少尉に任官後三年八ヶ月目に中尉に進級した。それから一ヶ月後に動員令が下ってシベリアに出陣することになった。自分にとっては全くの初陣である。帝国将校として朝鮮人としての面目を施す時は来たのだ。何と言っても軍人は実戦に臨まなければならぬ。弾丸の洗礼を受けて見て、初めて人間の真価が現れるのだ。今まで浮華文弱に流れ、腐り切った祖先を持って生れた朝鮮人が、いくら己は純粋なる大和魂の持主なり、日本人なりと言って見たところで、実績のない、証明の出来ないものに誰が信を置こう。

自分が朝鮮生れの大和人として、真に大和魂を把握している純粋日本人たることを立証し得るのは、千歳一遇のこの時機にあるのだ。然し私一個人としての事情はないではなかった。父が丁度陸士卒業半年前に亡くなって、家には母が一人と唯一人の未成年の弟がいるのみなのだ。而も任官以来唯一回休暇を賜わって帰って見ただけで家のことがどうなったか、その内容は一向に知らぬのだ。自分でなければ整理のつかないことも山ほどあった。家庭的に残っている問題は、可成りに多かったのだ。

◇―◇

時の連隊長に呼ばれて連隊長室に行った。

『君は今度出征することになったのだが、家庭のことでも何でも宜しいから、言い置きはないか?君が出征した後で、出来ることなら処理をしてやるから遠慮なしに言ってくれ給え』

ああ何という情深いことであろう。衷心感涙に咽ぶのであった。然し自分は静かに考えた。自分でなければ整理のつかないことがないでもない。然し自分は今大命に依って出征をするのだ。而も朝鮮人として日本人たることを立証すべき時なのだ。区々たる家事を云々すべき時ではないのだ。そう思った瞬間『何もありませぬ。喜んで靖国神社に参ります』ときっぱりと答えた。『あそうか。それでは確かり頼むぞ』ということであった。

◇―◇

釜山に上陸し満州を通ってシベリアに向かった。朝鮮を通って行くということは、予に取っては誠に奇縁であった。事々物々感無量ならざるはなかった。鉄道輸送の関係で釜山に二泊することになった自分に課せられた任務はなかった。家にはたった一人の老母とたった一人の弟がいるのみだ。

任官の翌年(大正四年夏)賜暇帰省で十日ばかり会っただけでそれから三年間帰省しなかった。而もこれから先は靖国神社での対面になるのだ。せめて一日位早く先発さして貰って、此の世の最後のお別れをしたかった。確かり母の胸に抱きついて、思う存分乳でも飲んで見たかった。母親の顔を忘れないように確かり眺めて見たかった。此の考えで胸が張り裂けるようだ。此の情には内地人も朝鮮人も変わりはないのだ。否寧ろ内地人の方が一層強いのかも知れぬ。然し自分は考えた。今自分は朝鮮人を代表して初陣に就くのだ。

先発だなどいい出したら、矢張り朝鮮人は家庭に未練があるのだ。生命が惜しいのだ、というような譏りを受けるかも知らぬ。ここは大いに考えねばならぬというので一言も口に出さなかった。唯弟に手紙を出して、通過の時母親を連れて龍山駅に出て来るようにいって置いたのであった。一晩は釜山で明かした。翌日の昼頃、突然停車場から電話が掛かって来た。同じ中隊附将校の電話であった。その要旨は次の通りであった。

『大隊長に申中尉(当時余の姓は申である)の家は京城にある。確かお母様一人だけであった筈であるから、一日先行さして会わしてやったら何うですか』と申し上げたら、大隊長は『そうか、それは気がつかなかった。旅客列車が今直ぐ出る。自分に挨拶などに来たら発車時刻に間に合わないから、挨拶は抜きにして今直ぐ行け。明夜十二時に龍山で合わせよ』と仰せられたから、今直ぐ出発せよとのことであった。

◇―◇

元々此方の希望して居ったところであるから、上司のお許しがあるとすれば、遠慮は要らない。直ぐに発って京城へ来た。母親とは十時間ばかり会うことが出来た。これで安心だ。何時靖国神社に往っても好いような気がした。

斯くの如く人情としては問題にもならないようなことでも、朝鮮人としては特別の決意を示さねばならぬほどの当時であったから、三十年前の朝鮮人が、日本人とするために如何に苦労したかは、想像に余りがあるであろう。シベリアに行った、征戦二年、自分としては別に大した勲功も樹て得なかったことは誠に恥ずかしいことであるが、然し卑怯な真似はしなかった。帝国の将校としての精神は傷つけなかった。朝鮮人の面目は潰さなかった積りである。二年目に帰って来た。軍部内の気分も明朗になって来た。然し是れで満足すべきではない。当時の朝鮮の一段の事情としては、未だまだ努力が必要である。妻を貰い、子供も続々出来て来た。然し余の人生観には更に一大変化を来したのだ。

それというのは、自分の初陣の目標は靖国神社にあったのであるが、幸か不幸か、靖国神社には行かずして、生きて帰って来た、然し是れからの自分は生きているのではない。とうにシベリアの屍となっているのだ。既に骸骨となって居るのだ。死人には感覚がない筈だ。ひねってもつねっても痛くはない。況んや苦しいとか、眠いとか、腹が減ったとか、いうような感覚があろう筈がない。死人となって働いてやろうという気持ちだったのだ。是れが即ち帝国のためであり、朝鮮のためなのだ。

◇―◇

内鮮融和の語は流行ったが、未だ未だ先は遠いのだ。依然として影は暗い。不平不満もある。軍に於いても我々同期生十三名と次の期二十名を将校とした外、一向に後継者を作っては貰えなかった。任官後十年経って漸く兵役法の一部の改正があって、朝鮮人に対する志願兵制度が成立せられ、陸軍幼年学校、士官学校、其の他の諸学校に朝鮮出身の有能の士にして、陸軍に志し採用試験に合格したものを入校せしむるようになった。

思えば帝国の陸軍に学んで六年、職を軍に奉ずること十年、血を以てする活躍の効顕れて、漸く我が半島に光が萌して来たのだ。何たる感激であろう。朝鮮人が真正なる大和民族となり、鉄石の如き信念に生き抜くための捷路は、身を軍籍に置く以外にないと確信して居ったからだ。

◇―◇

確か昭和四年か五年頃であった。満州事変前のことである。或る日連隊長に呼ばれて、その室に行った。一葉の文書を提示された。見ると、『朝鮮人のみを主体とする中学程度以上の学校の生徒に現役将校を配属し学校教練を実施するの可否』ということが書いてあった。これに関する意見の提出を上司より求められて来たのだ。遠慮は要らないから、腹蔵なき意見を筆記を以て提出せよとのことであった。

当時に於ける一般の気風は、内鮮融和の声が高く、且つ朝鮮人有識階級の凡てが朝鮮に義務教育の実施を熟望したり、徴兵制度の実施を一日も早からむことを懇願したりして、或は個人的に或は代表者を定めて、縷々要路の当局に嘆願書を提出したり或は直接中央部に出掛けて交渉をしたりしたのであった。

是れ偏に朝鮮人有識階級自らが、当時の朝鮮全体を、一日も早く皇民化せしめ、陰鬱なる気分を一掃して真に内鮮一体を実現せしめんとするの熱意に外ならなかった。然し当時の朝鮮としては、未だ未だ民度が低い、思想的に考慮を要する点も多々あったので、従って当局としては嘆願する度毎に時期尚早という理由の下に受け入れられなかった。

◇―◇

斯くの如き情勢に於いて朝鮮人学徒に軍事訓練を実施するの可否の問題が持ち上がったのである。自分は答えた。

「今日の情勢に於いて真に内鮮一丸の実を挙ぐるには朝鮮人をして一日も早く皇国臣民たらしむるにある。之がためには、朝鮮人をして一日も早く日本精神を体得し把握せしめねばならぬ。それがためには一日も早く徴兵制度を実施して軍人精神を体得せしむるにある。然し朝鮮に徴兵制度を実施するのには時期尚早であるから、少くも中学程度以上の学校に現役将校を配属して速やかに軍事訓練を施し、先ず朝鮮に於ける指導者階級をして、日本精神を把握せしめることが肝要である。何も彼も時期尚早で躊躇していたら、何時になったら内鮮一丸となることが出来るであろうか。現に私の如き朝鮮人が多少でもあるでないか。自分としても決して生まれながらに日本精神の持主ではない。元を導かぬれば正真正銘の朝鮮人である。その純粋なる朝鮮人が今日の如き日本人となったのは全く軍隊教育のお蔭である。それから考えても、今日の朝鮮人をして一日も早く皇国臣民たらしむる唯一の道は少くも学校に軍事訓練を実施するにある。どうか躊躇することなく快刀乱麻を断つ式に学校教練を実施して戴きたい」

ということであった以上は素より当局が既に方針を確立してのことであって、自分の貧弱なる意見が効果があったかなかったかは別問題として兎も角も翌年から試験的に京畿高等普通学校と平壌高等普通学校に軍事教練を実施することになり、実施後一年経つと教育の効果があるというので逐次全鮮に及ぼすことになり、今日のような状態を呈しているのである。

Source: https://archive.org/details/kjnp-1943-11-17/page/n4/mode/1up